Waste

Printing produces large quantities of sheets that are no longer required: trials and drafts and mistakes and various kinds of paths not taken. Printing is wasteful, or generous, depending on your point of view, and it’s usually one of the functions of a book to conceal this messy pre-history. The pamphlets and sheets that Gill, Dennis and I have completed have left behind countless pages and scraps: for every finished item there is a sea of other stuff, and what to do with this other stuff is an interesting question. Bin? Archive? Put on wall? It’s certainly true that a bound book composed entirely of these waste pages would be an interesting object: it would be a book, but also the inverse of a book.

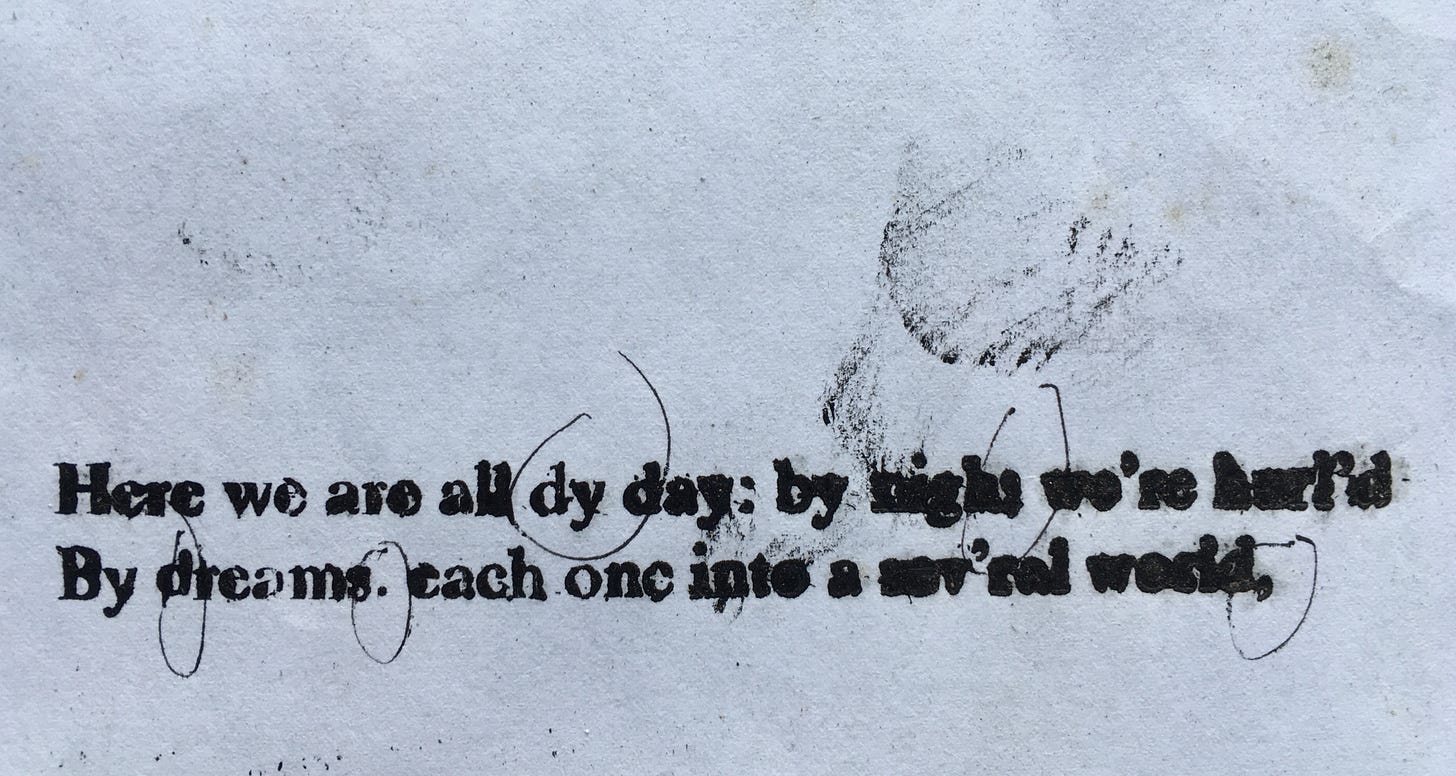

The waste we produce often takes the form of corrected proof pages, where the relationship between printing and error is played out with merciless visibility:

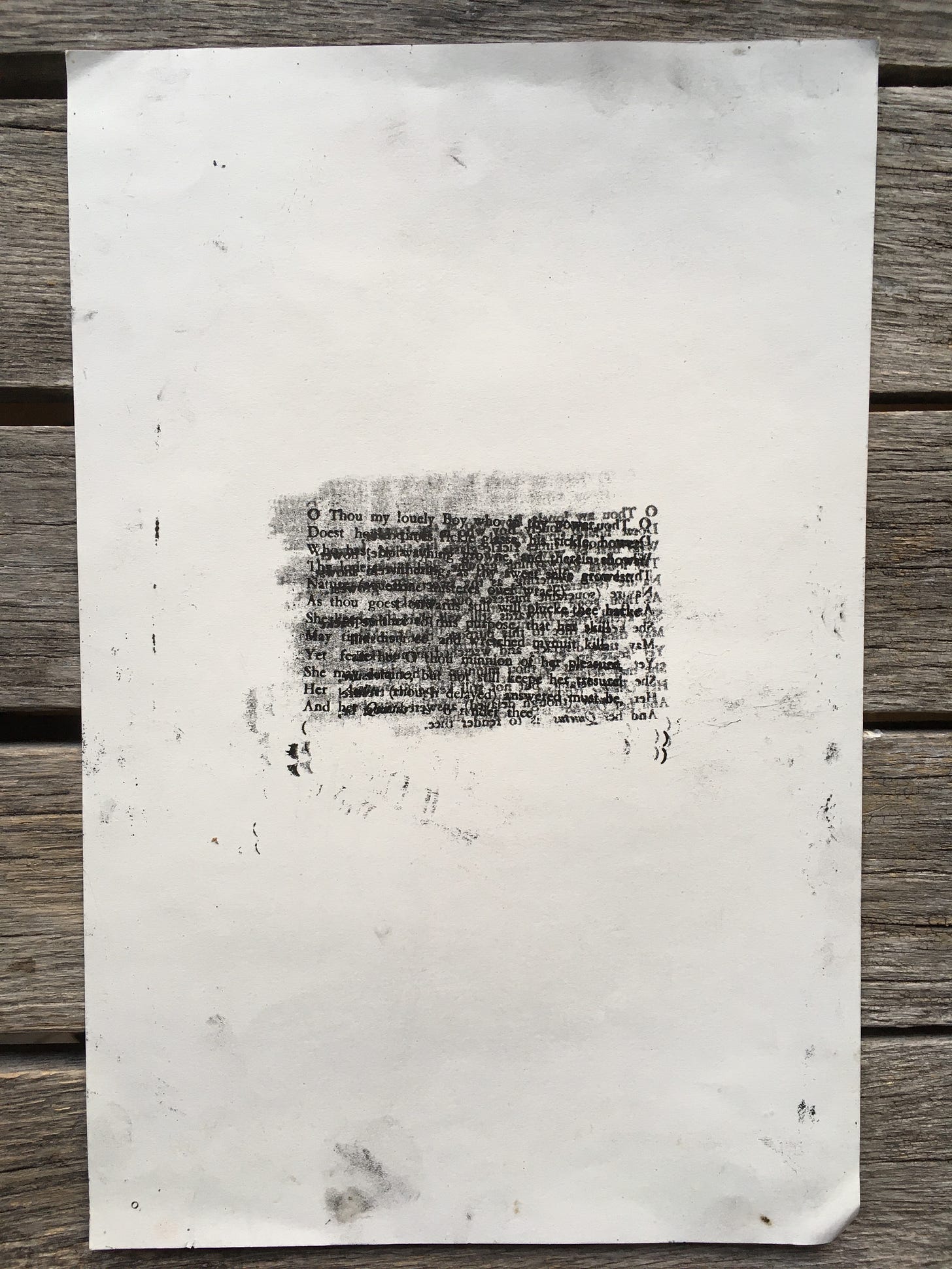

Some are trials that may or may not have led to finished things, like this experiment in over-printing Shakespeare’s Sonnet 126 (‘O Thou my lovely boy’):

There are also cruder, but no less interesting, kinds of residue – things like these:

Early modern printers in general pursued a principle of economy, and so tried to convert waste into profit. Printers often used unwanted pieces of texts in the physical structure of new books. No longer required proof sheets might patch together new books. A fragment of a printed proof of John Milton’s ‘Lycidas’, lines 23 to 58, complete with corrections in the hand of a worker at the print shop, survives because it was glued inside the back cover of Bonaventura Vulcanius’ De literis & lingua Getarum sive Gothorum (1597). For anyone interested in Milton’s print life, this is a jewel, extant precisely because it was deemed superfluous as text, but useful as a material support.

We can see something similar here in a copy of Francis Bacon’s The historie of the raigne of King Henry the Seuenth (1622) that sits now in the library of St Edmund Hall, in Oxford.1 It’s Bacon’s history of the first Tudor monarch, written soon after the author’s impeachment in 1621.

Looking closely, you can see that this particular copy has strips of printed sheets that are used to strengthen the binding of the book.

If we lean in, we can make out the text: at the bottom of the strip below, ‘Chapter 24 … foretelleth the destruction of …. How great calamities…signes of his coming to…’

This is from the Bible – Matthew, chapter 23. Looking carefully at the rest of the waste shows that, collectively, the waste covers passages from Matthew 22, 23, 24, 27, and 28: the description of Christ speaking to the multitudes and castigating the scribes and Pharisees as hypocrites; and, in 27 and 28, the platting of the crown of thorns, the crucifixion, the rolling back of the stone from the tomb, and the news that Christ has risen. After a few afternoons digging around comparing printed Bibles from the time with this slice of binding waste, we can figure out that our waste comes from unfolded sheets from an octavo edition of the King James Bible. There were 13 octavo editions of the King James Bible before 1622 (when the Bacon book is published): our waste comes from the 1620 edition.

Bacon’s book, then, carries within it parts of the King James Bible, as many books from the period carried pieces of earlier texts. Like many instances of waste, those tatters are partially legible: you can’t help but notice them; the binders made little or no effort to conceal them; you can, if you wish, if you think it appropriate, if you have time, read them, although what exactly reading means in those circumstances isn’t entirely clear, and whether or not you discern or imagine a connection between waste and main text depends on the kind of reader you are. But certainly, a moment in the production of this book is suddenly, briefly illuminated: a binder reaching for a pile of unwanted printed sheets from whatever was to hand, tearing a strip, grafting it into the Bacon book, and quite possibly using other pieces from this copy of the Bible for other volumes on his desk.

Books are made from other books in the most literal sense, and so books might be archives of older pieces of print or manuscript. And even as books generally seek to forget their ragged history of production, they often carry parts of that story with them.

There are lots of interesting recent pieces on recycled waste.

Tamara Atkin’s discovery of a fragment of a 12th-century French poem as waste is reported in the Guardian.

Anna Reynolds’ article, ‘Such dispersive scattredness’: Early Modern Encounters with Binding Waste’, is here.

Thanks to Paul Nash for sharing several instances of printed waste in Oxford libraries.

Those of us acquiring books in the late 1940s saw plenty of Waste without having to wait for the book to fall apart. I still have a school prize - Bertrand Russell's History of Western Philosophy, 2nd impression, George Allen & Unwin, 1947 - the dust jacket of which has part of an RAF map of Nieder-Kassel on its reverse. Being little read, the book and the jacket have both survived.

http://www.robstolk.nl/drukwerk/2018/stuff/ Following this link will take you to the website of the Amsterdam based lithographic printers robstolk, and specifically a little book or 'surprise offering', called Stuff, which has no ISBN, because it is the literal by-product of a larger book of the same name, lavishly documenting archaeological trove salvaged from the city's river Amstel, during the construction of a new Metro line. Given away for free at Tate Offprint 2018 to promote Stuff per se, the rubric is as follows 'This little book was made from sheets fished out of our bins. Before the press starts rolling at full capacity it is "warmed up" with makeready sheets that are then discarded.' Measures 25 x 72 x 104 mm