Thinking

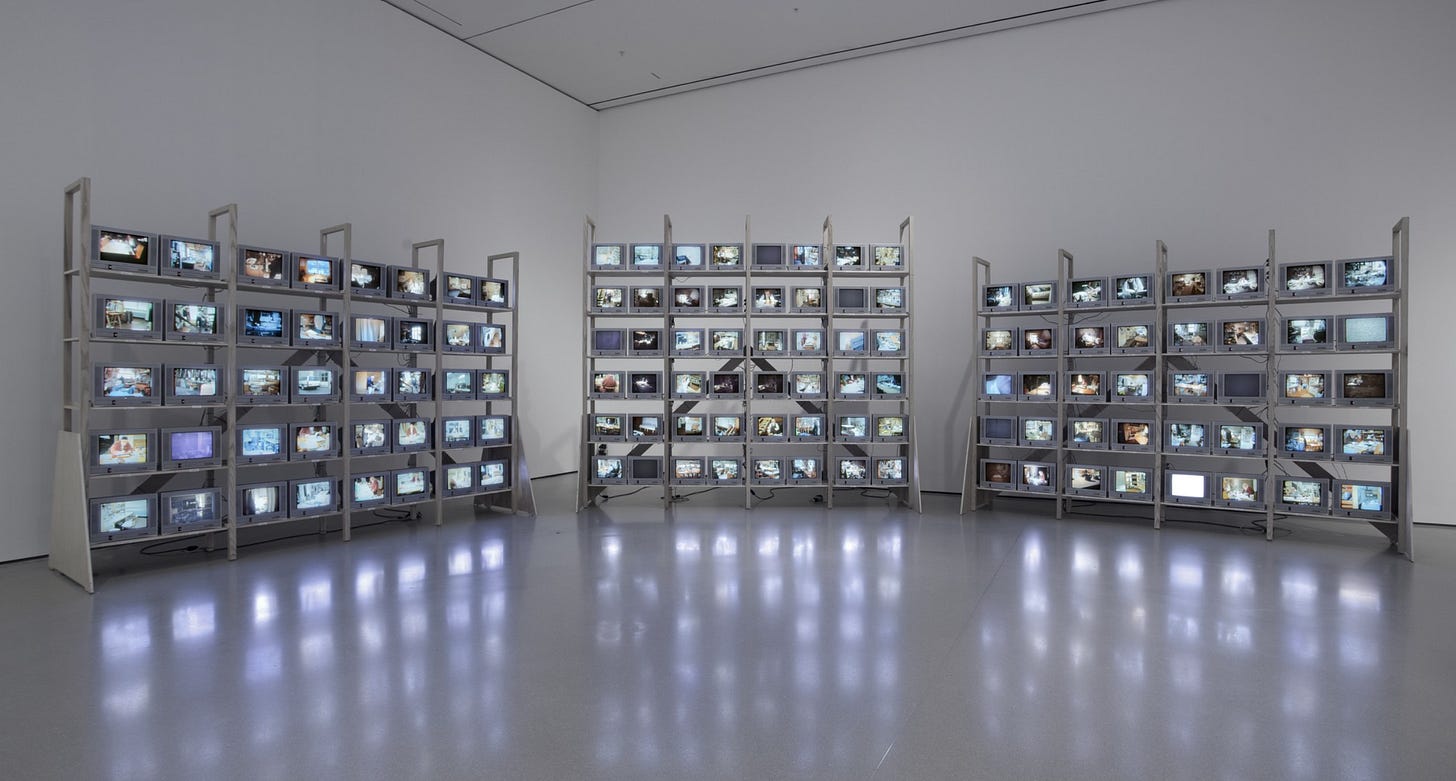

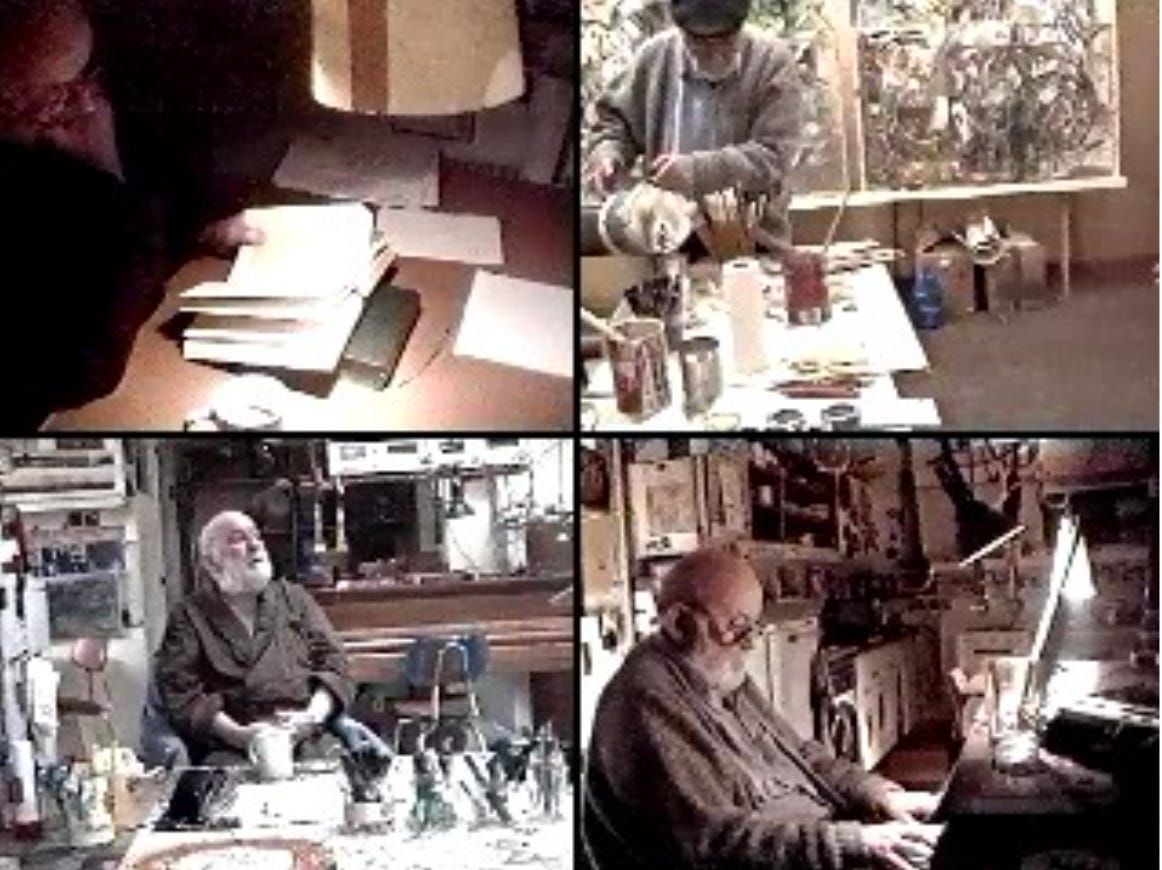

What does thought look like? For his 128-screen video work, Solo Scenes (1998), the Swiss artist Dieter Roth (1930-98) set up cameras in his house and several studios which recorded hundreds of hours of footage, from 3rd March 1997 to 28th April 1998. The footage captures the artist’s everyday life, while he attempts to recover from alcoholism, in his final year: it is a work of deliberate self-surveillance. Roth sits, sometimes drawing, often reading, or making notes, but also often simply sitting still and staring ahead. He gets up and walks slowly about. He sleeps. He hangs a shirt on a drying rack. He polishes his shoes. He plays the piano and then waters his plants. He sits on the toilet. He calmly turns the pages of the lamp-lit book he is reading.

Is this what late style looks like? Roth’s son and collaborator Björn said Roth ‘was filming himself dying’, and several critics have drawn a connection between Roth’s video diary and Rembrandt’s self-portraits. Roth himself said he was trying to capture an ‘intense Zero-ness’, and as we watch we feel both that nothing is happening, and everything. If this is interiority – if this is an artist’s creativity turning and coiling within – then its power is precisely that it is unreachable. Played out across 128 screens, Roth’s inner life is everywhere, but also beyond us.

I always thought the Roth of this video sequence looked uncannily like some representations of St Matthew. Caravaggio (1571-1610) was commissioned to paint canvases depicting Matthew writing his gospel for the Contarelli Chapel in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi, Rome, and produced four paintings which, in the words of one art historian, ‘open his mature period as a religious painter.’1 For the altarpiece, Caravaggio was asked to paint Matthew composing his gospel. His first version, Saint Matthew and the Angel (1602), above, was destroyed by the burning of the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin in 1945, but is known today through reproductions. The painting shows a thick-set Matthew, with crossed lumbering legs and eyes staring over the book in apparent bafflement as an angel physically guides his hand across the page – a movement which is, as Irving Lavin has noted, both pedagogical and inspirational2 – to produce a Hebrew script Matthew hardly seems to understand.3 This is a Matthew who seems ‘coarse, low brow’, even if the ‘bowling-ball head’ and ‘stocky gnarled body’ in fact – and ironically – recall the image of Socrates.4 It is an image of the author as cipher, a bulky bodily mass guided by divine powers, of thought not originating but passing through, of a writer seemingly unused not only to thinking, but also to the very weight of a book in his hands. Art historians have long loved what they call Caravaggio’s ‘revolutionary naturalism and proletarian’ sympathies,5 but the canons of San Luigi hated the painting. ‘The figure had neither decorum nor the aspect of a saint ... his feet crudely exposed to the public’6 – and the painting was rejected. Caravaggio produced a second, more refined depiction, The Inspiration of St Matthew (1602), more consistent with his other canvases of Matthew, and this painting resides in the chapel today.

Irving Lavin, ‘Divine Inspiration in Caravaggio's Two St. Matthews’, in The Art Bulletin 56.1 (March 1974): 59-81, 59.

Lavin, ‘Divine Inspiration’: 78.

James Kearney, The Incarnate Text: Imagining the Book in Reformation England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2009), 46-7.

Lavin, ‘Divine Inspiration’: 59, 70.

Lavin, ‘Divine Inspiration’: 59.

Giovanni Pietro Bellori, Caravaggio’s biographer, in his Lives of the modern painters, sculptors, and architects (1672), quoted in Lavin, ‘Divine Inspiration’: 79.