Pronting errors

In The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (1901), Sigmund Freud argues that slips of the tongue and the pen constitute moments when repressed thoughts break through. The taxing psychic labour of keeping buried thoughts at bay is momentarily relaxed, which is why, if we agree with Freud, that one of the effects of parapraxis is often a kind of joyous relief. Freud’s brief discussion of printing errors maintains the same central idea: that errors are meaningful as moments when ‘the real thinking … broke through’.1 Rather counterintuitively, Freud suggests that revelatory errors are particularly likely when printing, because the slower, mechanical production of texts means — he says — it is harder to inhibit those buried meanings. Amid the sustained physical strain of printing, Freud suggests, meaningful errors are more prone to spring forth — to ‘escape’, in the language of 16th and 17th-century errata lists.

It’s a fascinating question, the degree to which this Freudian model of error, based as it is around individual subjectivities, can help explain the generally collaborative, multi-agent world of printing. If a book has a printing error, whose repressed unconscious is bursting through? The author’s? The printer’s? The print shop’s? The book’s?

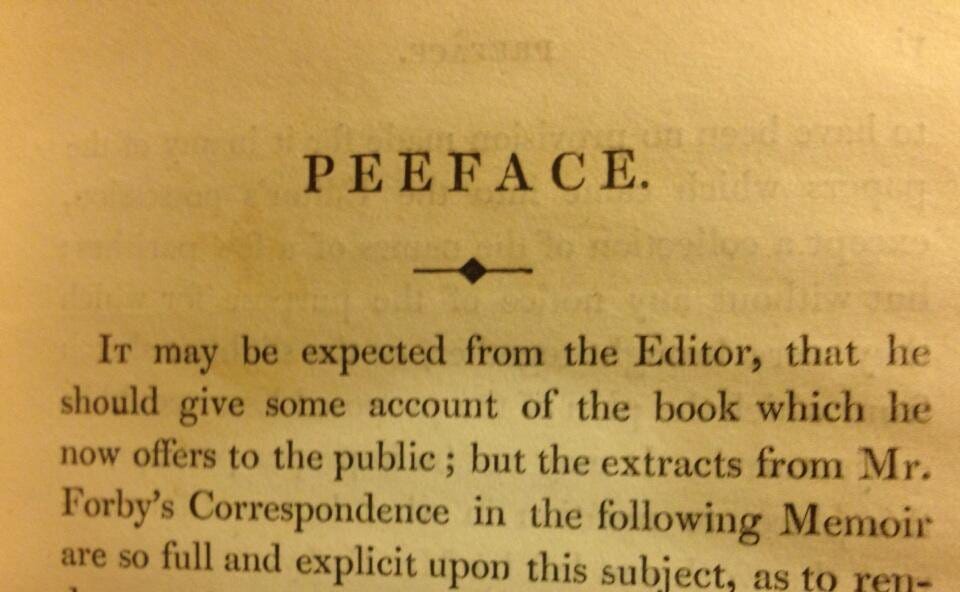

‘PEEFACE’, above, comes from the opening of Revd Robert Forby’s The Vocabulary of East Anglia: an Attempt to Record the Vulgar Tongue of the Twin Sister Counties, Norfolk and Suffolk, as it existed in the last 20 Years of the 18th Century, and Still Exists, with Proof of its Antiquity from Etymology & Authority (1830). The error was found by the novelist Melissa Harrison in a copy in Gladstone’s Library in Flintshire, Wales – the national memorial to the Victorian statesman, and four times Victorian Prime Minister, William Ewart Gladstone (1809–98), and Britain's only Prime Ministerial Library – although the slip seems to be common to all copies of this edition: the whole book, complete with Peeface at page v, is available on Googlebooks. Reverend Robert Forby (1759–1825), was an English philologist and rector of Fincham, Norfolk; The Vocabulary of East Anglia was his life’s work, although he died before completing it. His friend the Reverend George Turner, of Kettleburgh, Suffolk, edited and published the book in 1830, and penned the preface / peeface.

Printings errors are paradoxically most visible in moments of correction, which serve to mark out slips even as they purport to remove them. The errata list is one such bookish technology. One of print’s innovations, the errata list flourished from the early sixteenth century until the end of the seventeenth, although the form continued on after this date, too. It was one of the last parts of a book to be printed, catching errors which proof-reading and stop-press corrections had missed. Sometimes it took the form of a note of a necessary global change (‘Towards the midst, till the end of this Booke, for Getulia, alwaies reade Natolia’),2 but more common was the litany of substitutions – for this, read that – pegged to page and sometimes line or column number.

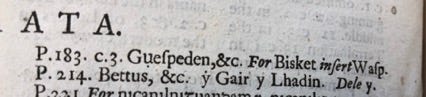

This one comes from Edward Lhuyd’s Archaeologia Britannica (1707), a study of ancient British languages – or, to give it its full title-page unfurling, ‘Some Account Additional to what has been hitherto Publish’d, of the Languages, Histories and Customs Of the Original Inhabitants of Great Britain: From Collections and Observations in Travels through Wales, Cornwal [sic], Bas-Bretagne, Ireland and Scotland’. Lhuyd was a Welsh botanist and linguist, and Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford from 1690, but that didn’t stop him (or his printer, or his scribe, or his proof-reader, or his book, or his historical moment), getting confused over ‘Guespeden’ which, in Cornish and Breton – as if I need to tell you! – means ‘wasp’ (or hornet), not ‘bisket’.

Paste-in correction slips were also quite common in seventeenth-century books. They’re inconspicuous to a quick scan of the page, and it takes some care, and some attention to the surface of the page, to notice the slightly embossed, often imperfectly aligned glued-on slip: passages of text which, in Jeffery Masten’s phrase, ‘rise up from the texture of the page.’3 In the 1611 Authorized Version of the Bible, printed by Robert Barker, Matthew 26: 36 described not Jesus coming to ‘a place called Gethsemane’ but Judas: the error meant that Jesus had to be pasted over Judas. Reading closely, as Protestants should, the disruption is clear: an off-kilter son of God, the ‘J’ of Judas peaking out beneath.

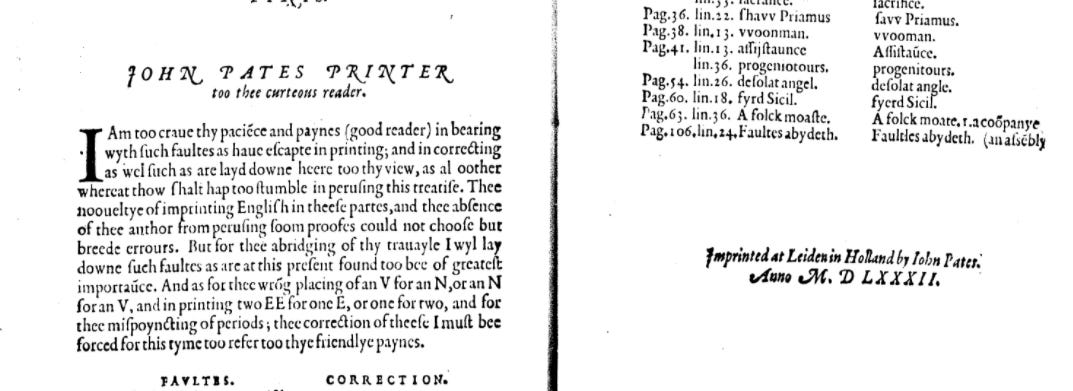

Errors also sometimes produce what we might call errata list justifications from the printer – explanations of what went wrong that are often miniature masterpieces of passive aggression and blame shifting. For the book historian, these micro-narratives can provide little glimpses of the book production process that we’d otherwise never know: in going wrong, the book reveals its own history. Here is Richard Stanyhurst’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid, printed at Leiden, Holland, by John Pates in 1582. Before reeling off a list of faults and corrections (including ‘vvoonman’ for ‘vvooman’), Pates asks ‘thee curteous reader’ patiently to endure and correct the numerous errors, before, less temperately, blaming the mistakes on a blend of ‘thee noouelttye of imprinting English in these partes’, and the absence of the author from the print shop.

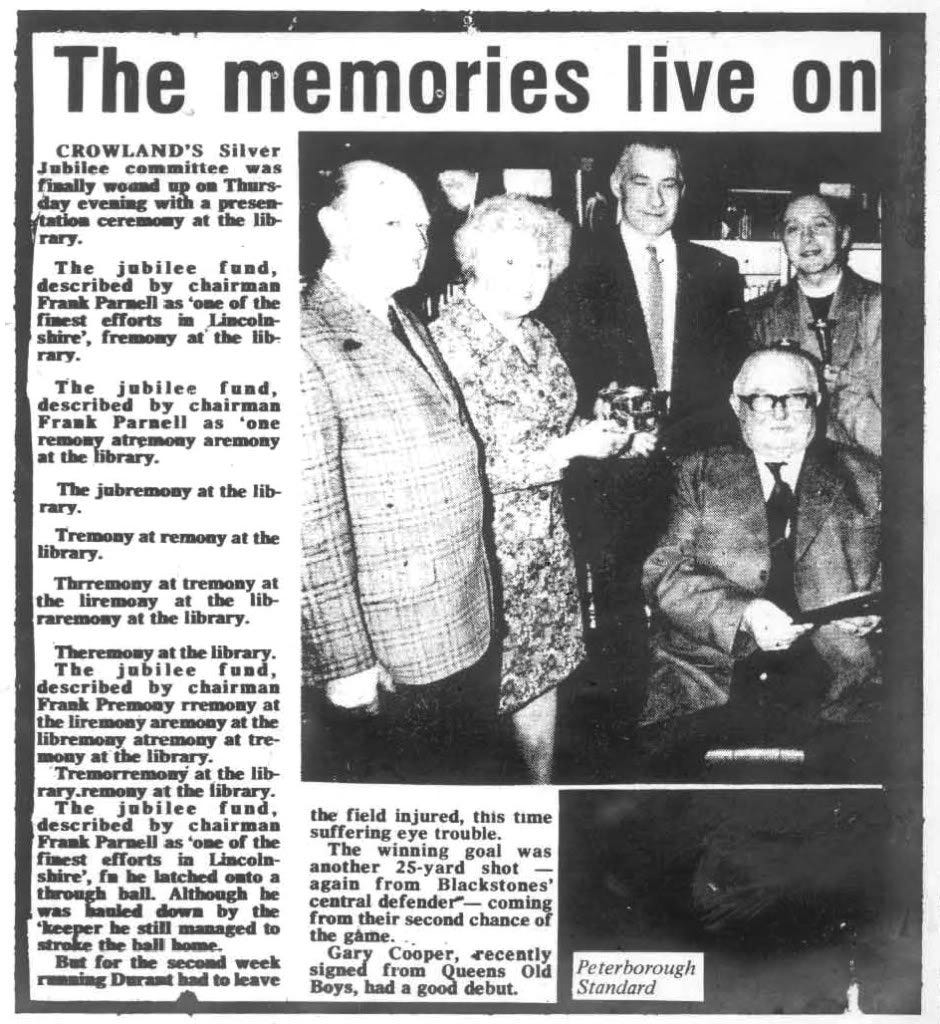

I’ll end with what may be the greatest printing error of all, but with no real explanation because I can’t understand how it happened. An article in the Peterborough Standard in 1979 begins as a piece about a silver jubilee committee but then starts to cannibalise itself, mixing in strange neologisms and word-fragments, before evolving quite suddenly into a clipped and tidy football report (the transitional moment is ‘he latched onto a through ball’). It’s best read as a kind of absurdist poem set in 1970s Peterborough.

Error scholarship is booming right now: for two excellent recent books, I recommend Erica McAlpine’s The Poet’s Mistake (Princeton, 2020), and Alice Leonard’s Error in Shakespeare: Shakespeare in Error (Palgrave, 2020).

Thanks to Adam Zucker and Sarah Pyke for sending vvoonman and tremony, respectively, my way.

Sigmund Freud, The Psychopathology of Everyday Life (London: Penguin, 2002), p. 116.

Emanuel Ford, Parismus, Part 2 (1599), sig. A4v.

Jeffrey Masten, “Material Cavendish: Paper, Performance, ‘Social Virginity,’” in Modern Language Quarterly 65.1 (2004), 49-68, 52.

This was a pleasure to read. As someone totally new to error scholarship, I would presume that the agency and intent are key themes especially when examined within the broader context of bureaucracy, in the case of large print media organisations. I look forward to checking out those book recommendations.