Inserting a pin through a folded copy of the AZ Street Plan of Oxford results in a series of 12 small holes spread across the unfolded map.

2 of these puncture the surrounding text, but 10 fall through specific points on the map, in and around Oxford:

Wyndham Way, off the Woodstock Road [map square G3]

Victoria Road at Lucerne Road, Sunnymead [J3]

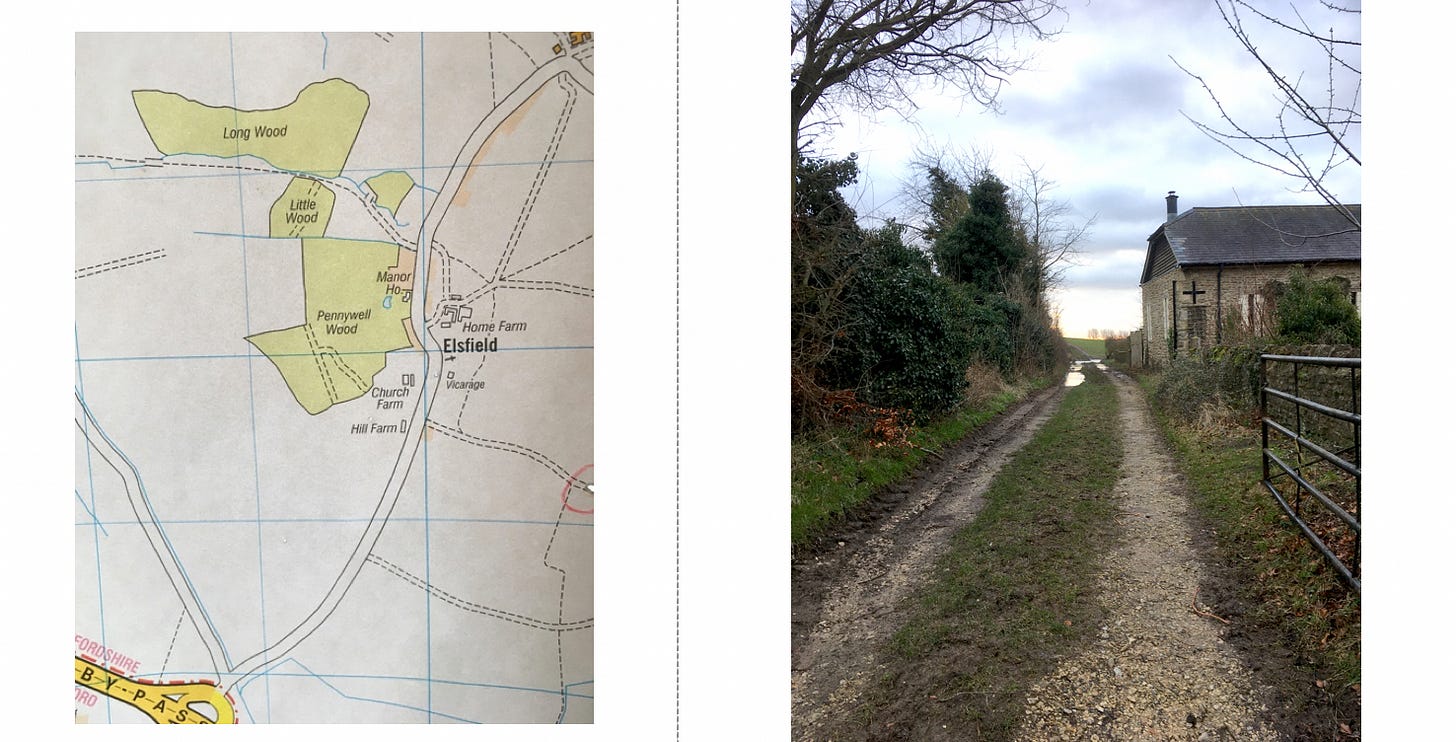

An unnamed track by the vicarage, Elsfield village [Q3]

Hinksey Road, off Botley Road [G10]

Oxfordshire County Council, Castle Street [J10]

Churchill Hospital, Churchill Drive [Q10]

Nuffield Road, Headington [S10]

Bagley Wood, off Badger Lane [H17]

Nuffield Industrial Estate, Spring Lane, Littlemore [R17]

Orchard Meadow Primary School, Blackbird Leys [S17]

Readers in seventeenth-century England seeking to see through the fog of the future were prone to opening at random their copy of Virgil and sticking in a pin: the skewered verse was understood to hold prophetic power. John Aubrey describes how in December 1648, while the not-long-for-this-earth King Charles I was in prison at Carisbrooke awaiting his trial, the poet Abraham Cowley (who ‘always had a Virgil in his pocket’) encouraged the Prince of Wales to insert a pin in the Aeneid. The point landed on Dido’s curse in book 4 (4.614-20), which Cowley translated ominously as ‘And life at once, untimely let him dy, / And on an open stage unburied ly’.

Or at least that’s what people say: the event circulates as an anecdote. What’s clear is that the practice of sortes Virgilianae, or Virgilian lots, was a widespread form of bibliomancy, and is just one iteration within a long tradition of aleatoricism in reading, running at least from the I Ching through the Dadaists of the 1920s to the present day. (My favourite example is Simon Morris’ 2003 scattering of thousands of cut-up pieces of Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams from the window of a speeding Renault Clio.) The practice of Virgilian lots assigns agency both to the book (which reveals, however cryptically, the future) and to the reader (who stabs the pin).1 Part of this ritual’s strange power comes from its blend of the highly material – a pin plunged into a printed book – and the highly immaterial – the book as all-seeing text, floating outside of time.

The Prince of Wales’ pin pointed to a gloomy passage on a single page. On my AZ Street Plan of Oxford, the pin pierces the several layers of the folded map to isolate not just one spot, but many, and to draw into a relationship these locations that would remain otherwise disconnected.

In creating a path that is impossible to walk, the pin reveals something about the way surfaces store information and create meaning. When the map is unfolded, Oxford lies on the surface of the paper in a way that corresponds with reality. Folded up, Oxford becomes a series of rectangular layers, one section stacked vertically on another, and new correspondences become possible. Something similar happens every time we close a book, and, hidden from our eyes, the logic of the page flips: words that, book open, acquire meaning through their relationship with neighbouring words on the page, are now pressed against words on facing pages.

Penelope Meyers Usher, “Pricking in Virgil”: Early Modern Prophetic Phronesis and the Sortes Virgilianae’, in Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies (2015) 45 (3), 557–571.

I *was* going to mention the wonderful app version for iPad and iPhone of Tom Phillips's "A Humument", which features a well-implemented random "Oracle Feature". However, it seems it is no longer available in the App Store, apparently because it was very much an in-house development, and the TP studio lacked the expertise to keep up with Apple's infuriating tendency to introduce OS upgrades that are not backwardly compatible with older software.

I hope the fate revealed by your chartomancy was benign, or at least suitably ambiguous. My feeling is that you probably ought to convert your pinpricks into six-figure OS grid references, and pass them through an alphanumeric decoding system, ideally similarly derived by random selection. Give chance a chance!

Mike