Grangerising: exploding and ballooning books

In 2016 I bought a 1904 copy of Edinburgh and Its Story by the Scottish journalist and author Oliphant Smeaton. What interested me, apart from the author’s spectacular name, was not so much in the text itself, but the way an owner had at some moment in the past inserted newspaper cuttings, postcards and other materials relating to the book’s subject: using the codex as a kind of folder, or box, or frame for storing related information. These extra inserts are often pasted on the end-leaves, like this:

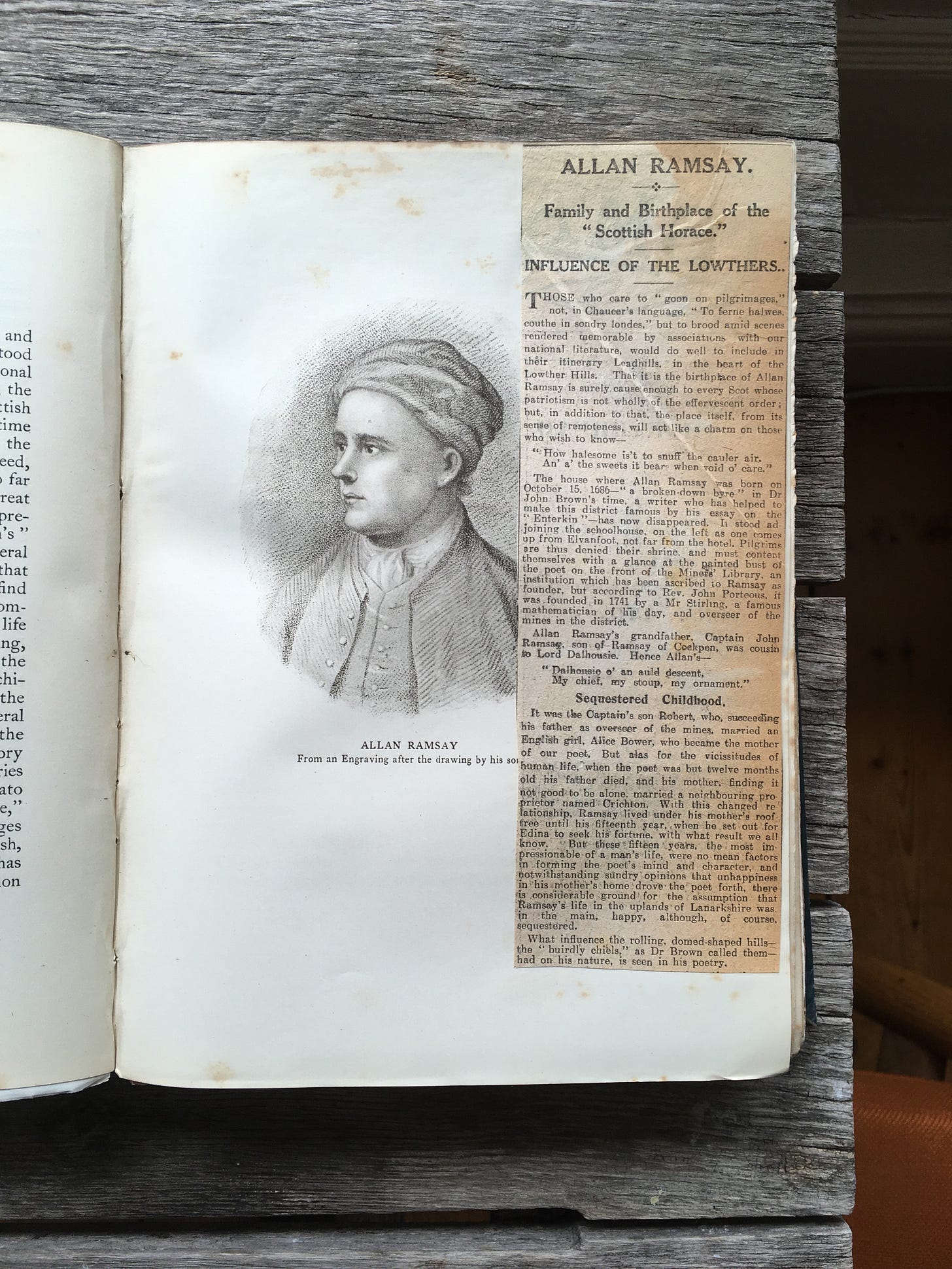

At other points, the add-ins are laid over the original text.

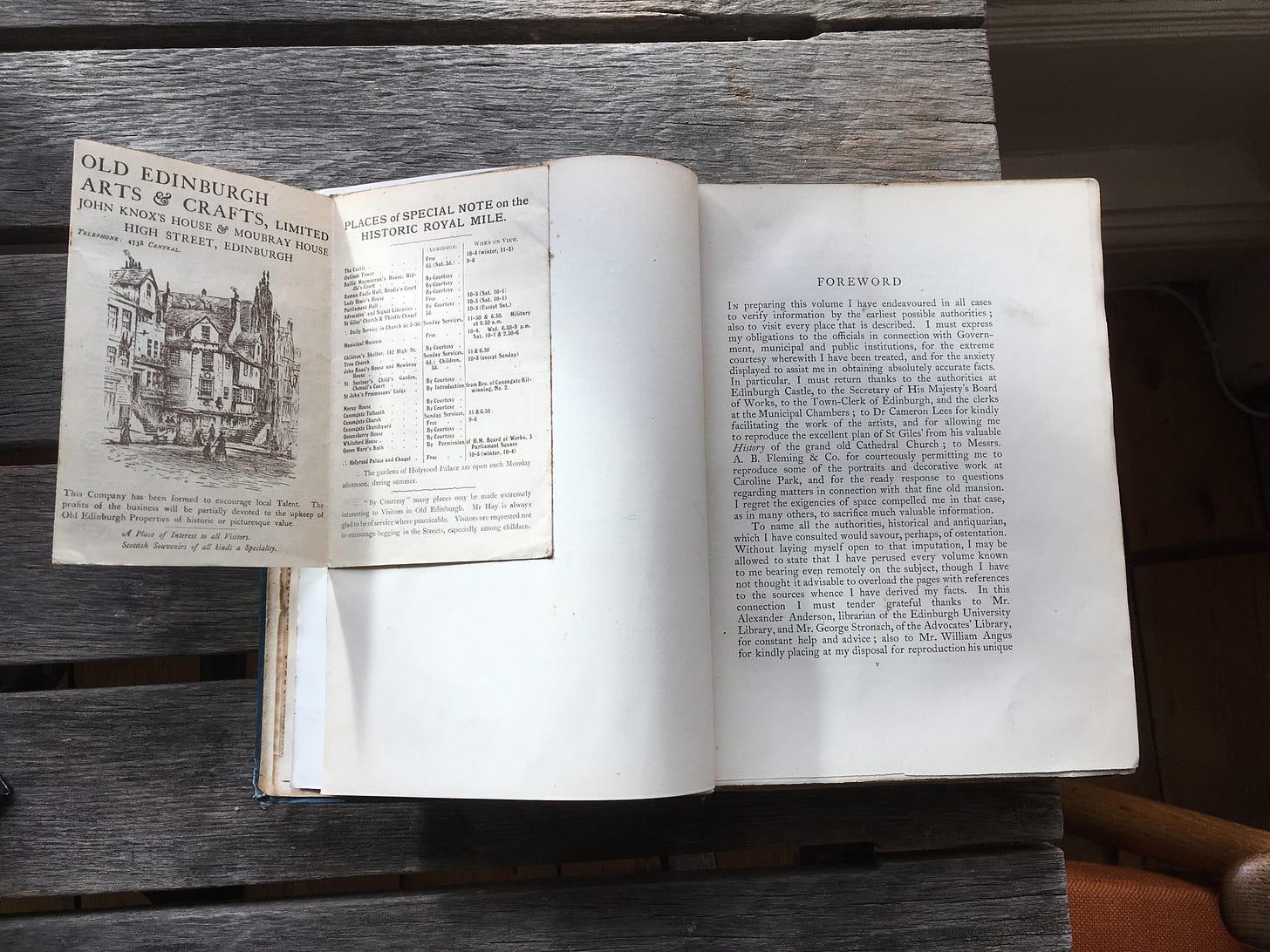

Elsewhere, the owner has glued in a whole separate pamphlet about Edinburgh: a booklet contained within the book, creating a page that unfolds onto a page that unfolds.

There is a tradition at work, here, known as Grangerising or extra-illustration: the insertion of prints and related materials into a book, resulting, often, in a huge expansion of the physical volume, a kind of ballooning which sometimes gets out of control.

In 1769, James Granger published A Biographical History of England, from Egbert the Great to the Revolution, Consisting of Characters Dispersed in Different Classes, and Adapted to a Methodical Catalogue of Engraved British Heads. Intended as an Essay towards Reducing Our Biography to a System, and a Help to the Knowledge of Portraits. Those were good times for book titles. Granger’s book had no illustrations. The expectation was that readers would insert images according to the series of biographies included in the book: the book was a call for readers to intervene and augment. What began in copies of Granger soon spread to other books; Isaac Walton’s Compleat Angler (1653) and James Boswell’s Life of Johnson (1791) were often given the treatment. Sometimes readers glued in loose prints, in the manner of our 1904 Edinburgh augmenter. More adventurous Grangerisers disbound their books and added in new blank pages to hold prints, or, with less bulge and more elegance, cut windows in sheets and inlaid insertions, before rebinding.

Grangerising is a balance of destruction and creativity: a book is cut open, pulled apart, separated out, blown up, we might say, and turned into something else. In the process, a printed book, of which there might be thousands of identical copies, becomes a single, unique item: a document of a particular reader’s taste. Grangerising also jettisons the idea that a book is or ever can be finished. There are always more prints to find, always more extras to paste in. Why stop?

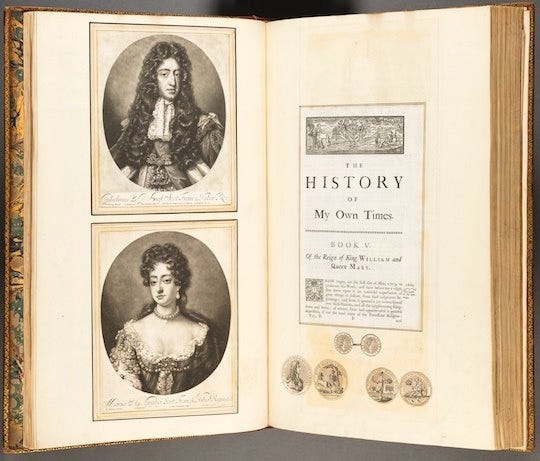

We see the vertiginous consequences of this logic playing out in richly extra-illustrated volumes. The MP and landowner Richard Bull (1721–1805) was a particularly assiduous Grangeriser. He was a MP, but never once spoke in Parliament, distracted perhaps by the higher calling of cutting and pasting. Bull inserted so many additions to his copy of Granger’s Biographical History that the original single book turned into 36 large folio volumes, now held at the Huntington Library in California. Here, below, is a piece of Gilbert Burnet’s History of My Own Time (1724), in Bull’s collection: page one of book 5, ‘On the Reign of King William and Queen Mary’, inlaid into a larger sheet, and put into some kind of dialogue with two portraits and 6 medallions.

To turn pages like this is to be in the presence of both a meticulous bibliographical care, and an anarchic spirit of cutting, disbinding, remaking, exploding – an engagement with books that is both bibliophilic and bibliophobic. According to publisher Holbrook Jackson, writing in The Anatomy of Bibliomania (1930), Grangerising was ‘a singularly perverted idea, conceived at a time when there were no book-lovers … a vehement passion, a furious perturbation to be closely observed and radically treated wherever it appears.’

My favourite example is the Sutherland Collection in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford: a spectacular set of extra-illustrated books produced by wealthy merchant Alexander Sutherland and his wife Charlotte, between about 1795 and 1839. The two of them – and then Charlotte alone, after her husband’s death – collected prints to extra-illustrate Clarendon’s The History of the Rebellion and Civil Wars in England (1702-4) and Burne’s History of My Own Time (1724). In some ways it seems an odd thing for a husband and wife to devote their time to, the insertion of thousands of prints into disbound volumes of history books. ‘Darling do you think we should stop – it’s nearly 1am?’ But Grangerising gripped them, as it did the lives of many bibliophiles in the 18th and 19th centuries: the Sutherlands produced 216 volumes, containing 18,742 prints and drawings, and 14,849 portraits. 713 of the portraits were of Charles I, and 518 of Charles II: there is a strong Royalism to the Sutherland’s Grangerised books, which speaks both to their particular politics, but also more fundamentally to the Grangerised book as a mechanism of memory – a way of gathering and holding, and also of reorganising history into a narrative more favourable to their cherished King Charles I. One could weight the past in new directions through the accumulations of a Grangerised book. For the Sutherlands, a book was an object to be altered and remade over and over, expanded and refined, a process of variation that took the book further and further away from its original form, but that in doing so produced a new object loyal to the original. The theorist and book historian Juliet Fleming describes a book as an object which, in changing through time, ‘differs from itself’:

we must entertain the possibility not only that books are things, rather than ideal entities, but that they are one of the large class of things that must be viewed in time, as having duration, and a way of being that is revealed most fully in their dissolution. The book is a thing that differs from itself, at all the moments of its production, and at all the moments of its consumption, and the only way to make responsible decisions concerning the identity and the preservation of such objects is to begin by admitting the inordinate complexity of the task.1

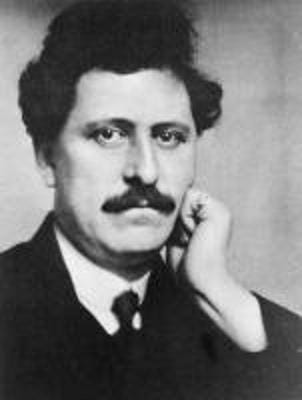

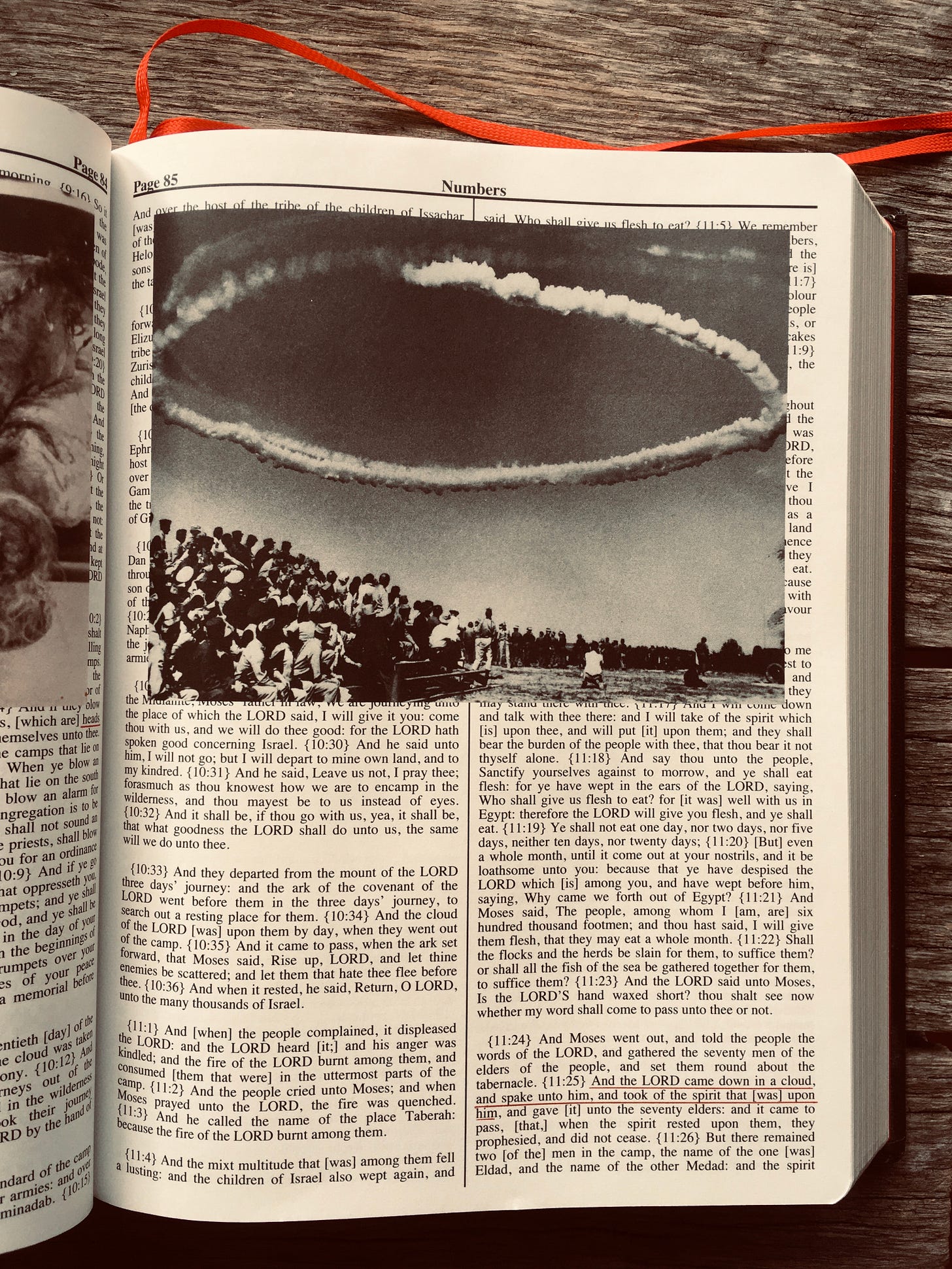

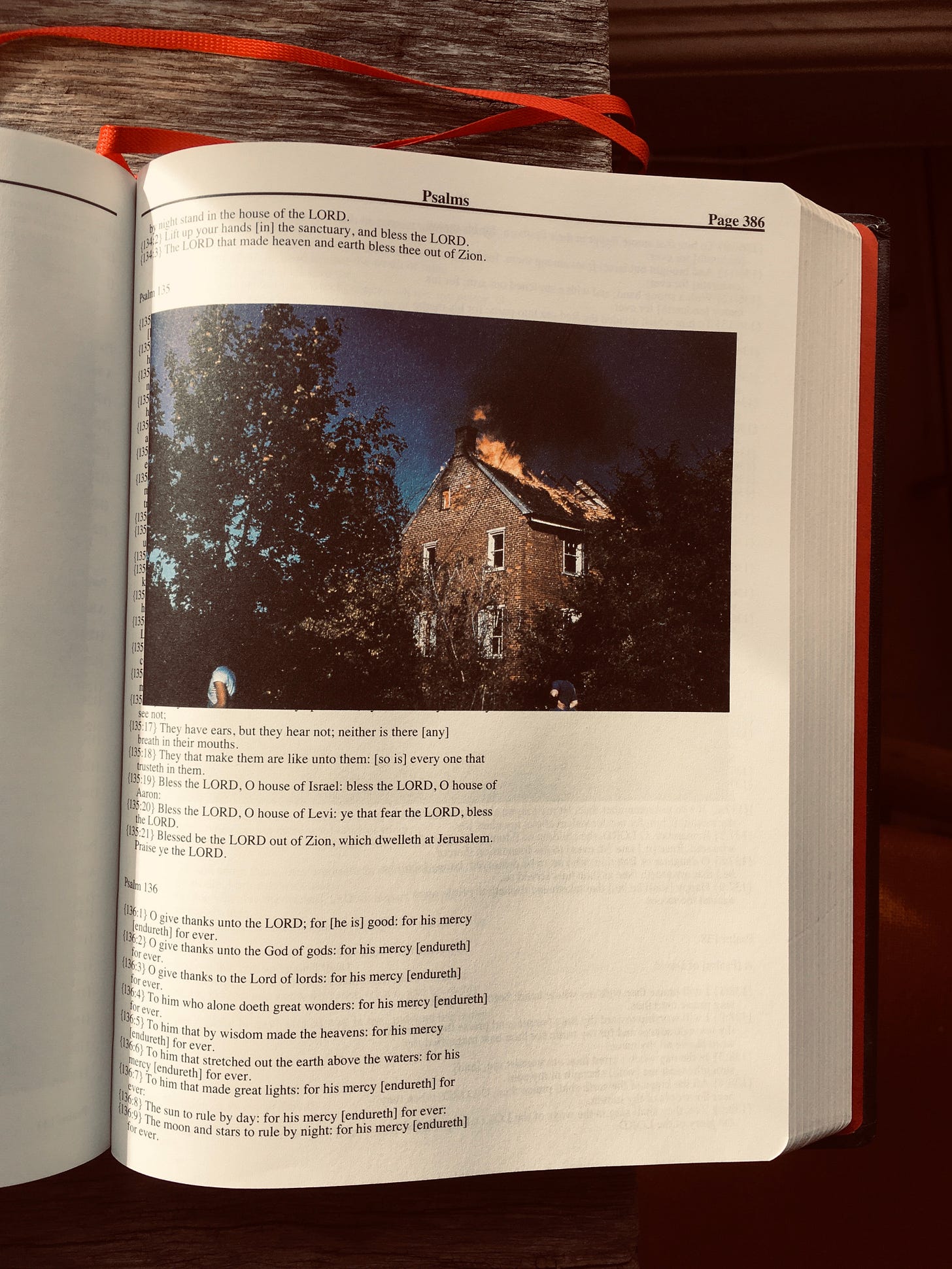

The legacies of the Grangerised book are many but for my money the most powerful, and disturbing, is Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s Holy Bible (2013).

This is a copy of the King James Bible, complete with a title embossed in gold, cigarette-paper-thin pages, and a red silk bookmark: the kind of thing that might rest unread in a hotel bed-side drawer. But it’s an altered Bible. Lines have been underlined in red, and images have been printed over the text, as if glued on top.

The relationship between underlining and image is sometimes, but not always, clear; and while some of the effects are surreal or even comic, and all are strange, in general the images work to draw out the various kinds of violence and suffering contained within the text. (The pictures come from the Archive of Modern Conflict, a London archive of found material relating to the history of war.)

Broomberg and Chanarin don’t use the term, but their Holy Bible is in effect a photographic reproduction of a Grangerised book.

I’d recommend these for more on Grangerising or extra-illustration:

Lucy Peltz, ‘Facing the Text: The Amateur and Commercial Histories of Extra-Illustration, c. 1770-1840’, in Owners, Annotators and the Signs of Reading, eds. Robin Myers, Michael Harris, and Giles Mandelbrote (New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll, 2005), pp. 91-135

Erin C. Blake and Stuart Sillars (eds), Extending the Book: The Art of Extra-Illustration (University of Washington Press, 2010)

Luisa Calè,’Dickens Extra-Illustrated: Heads and Scenes in Monthly Parts (The Case of Nicholas Nickleby),’ The Yearbook of English Studies 40 (2010), 8-32.

Juliet Fleming, ‘Afterword’, in Huntington Library Quarterly, Vol. 73, No. 3 (September 2010), 543-552, 552.

This is fascinating and inspiring! We are both annotators (Neha writes in a separate book journal, I write and tab directly in my books) but we'd never thought about expanding it in this way -- this post has got our wheels turning...

- S

Amazing write-up, I was hard-pressed to find any useful material on Grangerizing until your post showed up in a reference. I've also made a few insta stories about this topic and have cited your blogpost and used two pics and a few quotes, giving full credit.