On a visit to my brother’s last weekend I saw the Bible which has passed down on my mother’s side of the family, looming on a high shelf. It’s very large and very heavy and was rebound about 10 years’ ago.

It’s an undated edition from around 1860, a Bible with commentary that seems to have no end, by the prolific Rev. Robert Jamieson (1802–1880), a minister at St Paul's Church, Provanmill, Glasgow. Here’s the title-page:

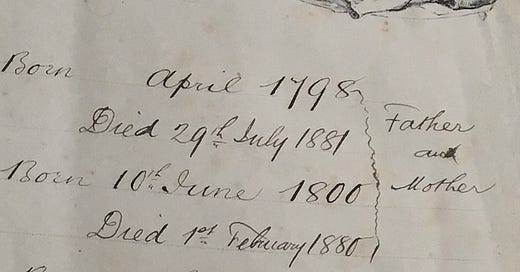

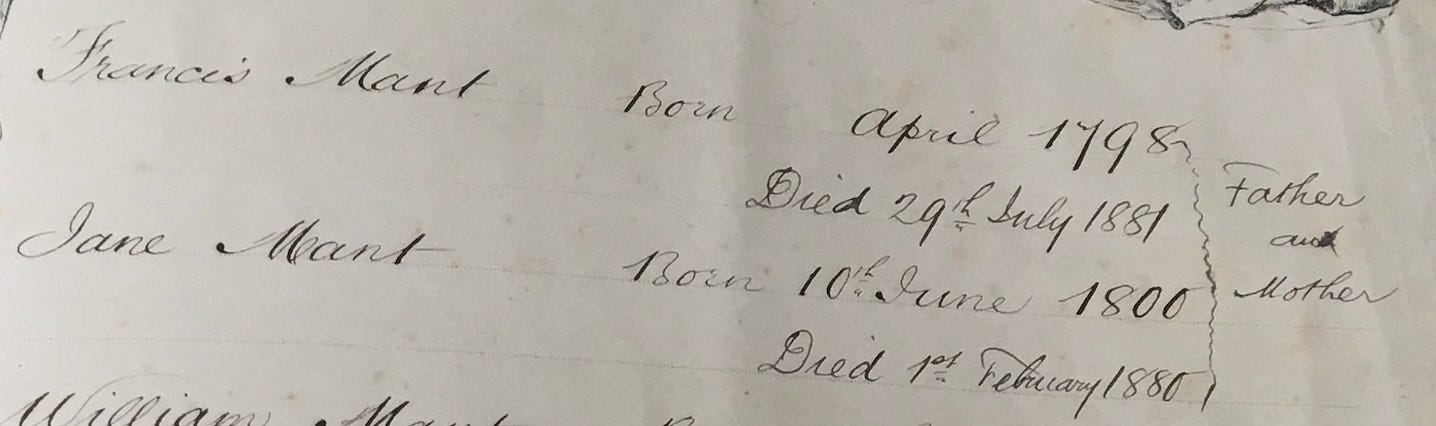

The two pages that preface the text are covered with handwritten annotations, mostly from the nineteenth century. The right-hand page lists a series of names and dates, starting with ‘Francis Mant Born April 1798 Died 29 July 1881’ and proceeding through births and deaths within the Mant and Bassil families.

You can see the first names a bit clearer here:

On the facing page, the Mant and Bassil families join in the marriage of Thomas Mant and Georgina Bassil – my great great grandparents, although I only dimly knew that until I took a closer look at the weekend. Their children follow, further down the page, and then my grandfather’s careful hand has carried on the list up until the 1990s, concluding with my cousin’s children who live in Australia.

These kinds of lists of micro-biographies, added to the opening of a Bible, are reasonably common, particularly in the nineteenth century, and often represent the only gathered account of the history of many families: family history as punctual information, as a series of brisk vaults down the generations. It’s what George Eliot describes in The Mill on the Floss (1860), when, in Book 3, Chapter 8, Mr Tulliver examines ‘the quarto Bible … laid open before him at the fly-leaf’:

‘Ah,’ he said, looking at a spot where his finger rested, ‘my mother was Margaret Beaton; she died when she was forty-seven, — hers wasn't a long-lived family; we're our mother's children, Gritty and me are, — we shall go to our last bed before long.’

Adding a genealogy like this makes sense in Bibles which themselves rehearse ancient family trees: ‘Rose Gertrude married George Percival Shippam at All Saints Church Chichester on 8th September 1898’ is a dim but very English echo of ‘And Judas begat Phares and Zara of Thamar; and Phares begat Esrom’. A Bible must have appealed also as a record-keeping space because it was the domestic object most likely to endure through time, and to remain part of the family – although the piles of annotated family Bibles offered for sale online suggest that this wasn’t always the case. The affective power of the list of names comes from that sense of earlier generations trusting later generations to carry on the work. This is a collaboration between people who could never meet.

The engraved borders encourage these kinds of handwritten annotations: by the time my family Bible was printed around 1860 (there isn’t an exact date), publishers were well aware of what readers had long been doing with their Bibles, and often built into the printed texts paratextual spaces to cheer on this kind of annotating. Versions of these family-annotations-in-printed-Bibles were becoming common by the late sixteenth century. As Femke Molekamp has described, an Elizabethan woman named Susanna Beckwith took her Geneva Bible and wrote an inscription to her daughter, also called Susanna, who would inherit the book:

Susanna Beckwith my deare childe I leaue the this booke as the best jewell I haue, Reade it with a zealous harte to understand truly and upon all thou readest either to confirme thy faith, or to Increase thy repentance ….1

And, as Katherine Acheson has described, a Book of Common Prayer (1682) now at the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington DC, carries the note, ‘Jane Clare her Book and was baptized the first day of August 1672.’2

These inscriptions represent a reader’s impulse to assert her presence, her place in time, her relationship to an important book, and that evidence of her aliveness is still legible today. These inscriptions have a kind of depth or texture because they record both an exact moment when the note was written (the I-am-here-ness), and immediately imagine a future when that record will be read as past (the I-was-here-ness). We can see a fuller version of this genealogical impulse in the 1612 King James Bible that once belonged to John Milton (1608-74), now in the British Library. It’s a fragile, battered volume, full of marks of use and the stresses and strains of frequent devotional reading which, of all modes of reading, was the most bibliographically violent. The flyleaf contains Milton’s handwritten records of the births and deaths of his family, beginning with his own birth on 9 December 1608, and the cheerfully vague note of his brother Christopher’s ‘about a month before Christmas’ in 1615, and then on, through the family. (Milton was blind by 1651 and the handwriting changes in 1652.)

You can read more about these kinds of annotations in excellent articles by Martine van Elk here and here, and by Kate Gibson here; in Margaret Connolly, Sixteenth-Century Readers, Fifteenth-Century Books: Continuities of Reading in the English Reformation (Cambridge University Press, 2019), chapter 5, ‘Books and their Uses’; in Femke Molekamp, Women and the Bible in Early Modern England (Oxford University Press, 2013); in Katherine Acheson, ‘The Occupation of the Margins: Writing, Space, and Early Modern Women’, in Acheson (ed.), Early Modern English Marginalia (Routledge, 2019), pp. 70-89; and in Renske Hoff’s ‘Safekeeping memories of transition and trauma in sixteenth-century Dutch Bibles’, forthcoming in TXT Yearbook (Academic Press Leiden).

Thanks to everyone on Twitter who replied so generously to my question about this practice!

Femke Molekamp, Women and the Bible in Early Modern England (Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 36-7. Beckwith’s bible is now at the British Library (BL 464.c.5.(1)).

Katherine Acheson, ‘The Occupation of the Margins: Writing, Space, and Early Modern Women’, in Katherine Acheson (ed.), Early Modern English Marginalia (Routledge, 2019), pp. 70-89. The book is Folger B3668.2, back flyleaf.

I was interested to see the link to familybibles.org.uk, which I shall pass on to one of my ex-colleagues. A familiar experience to anyone who has worked on the Reference Desk of a university library is the "elderly person with a carrier bag" (a.k.a. The Antiques Roadshow Experience). This bag usually contains a large 19th century tome, usually a Bible or a Shakespeare, which "has been in the family for generations, and must be of some value". It can take some considerable tact and patience to persuade them otherwise.

Mike