1. Pavel Büchler (b. 1952)

Pavel Büchler’s Idle Thoughts is a collection of the artist’s diaries covering the years 2003, 2004, 2005, 2007-8, and 2010-11. Each page is the product of a month of daily entries, written in pencil or biro: rather than proceeding across the space of the diary, as we might normally write, the entries are written and overwritten on this single page, layering and layering the text. Büchler published a catalogue of these 12 overwritten months, and then set about writing on each of these pages for the appropriate month of the next year, adding diary entries on top of diary entries. These were themselves then published, and the process of layered writing continued. We say something is ‘overwritten’ when we mean it is rhetorically over-heated, but here the writing-on-top-of-writing is literal.

Each page contains Büchler’s thoughts and experiences, but layered so many times as to produce illegibility. The density of the content means we can’t read it – except occasionally a glimpsed letter, or letter fragment, at the end of a line where the overwriting grows less intense. For the 2004 text – ‘A Year with a Dead Biro’ – Büchler wrote with ‘an exhausted biro’ that had no ink, creating a blind impression that is both full and empty at the same time. This unyielding quality prompts certain fundamental questions about the process of mark-making. Should we think of writing as something that covers up, rather than reveals? And when does text become picture, and writing become drawing?

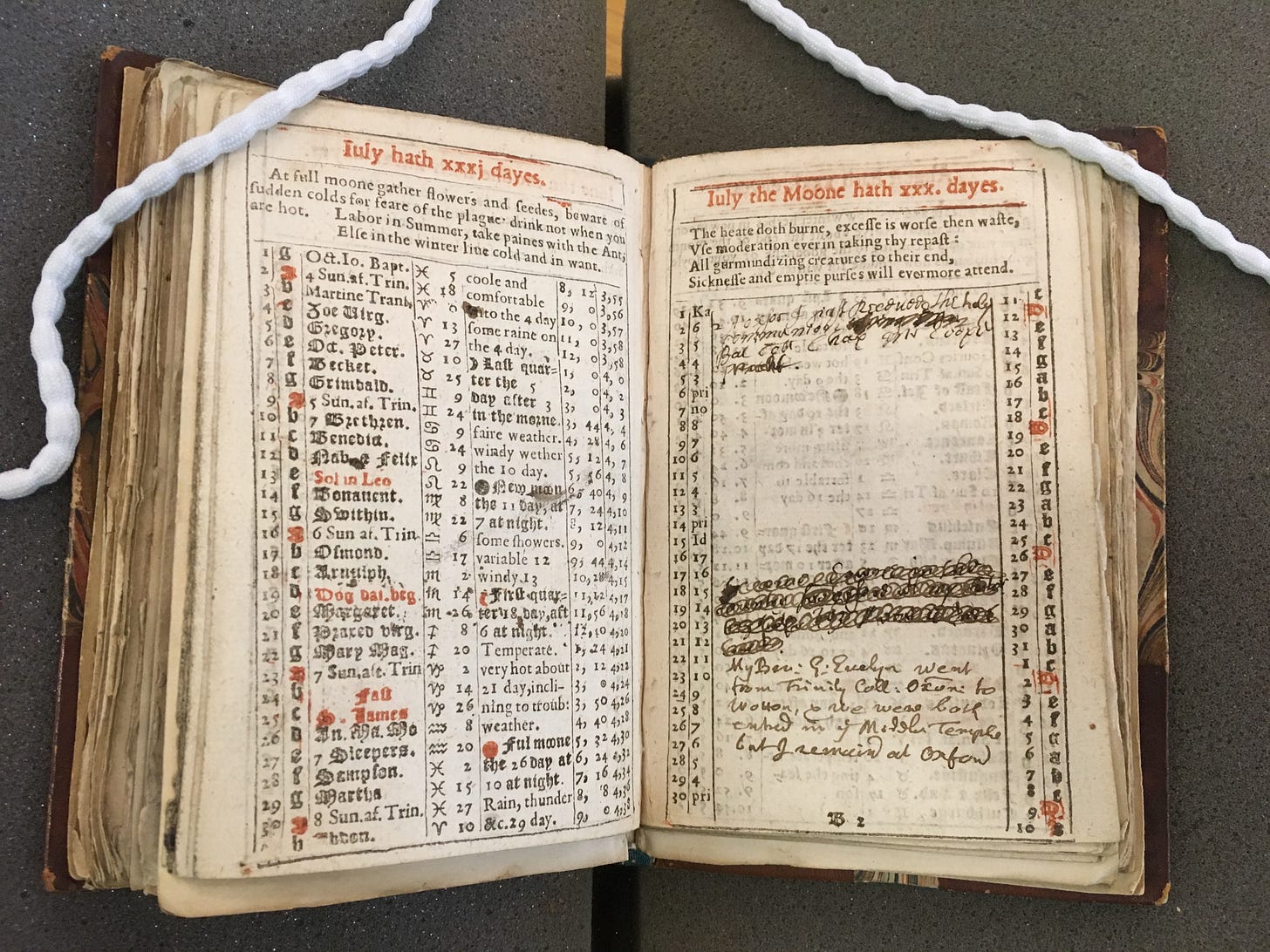

2. John Evelyn (1620-1706)

From the age of 11, the future antiquarian, courtier, and gardener John Evelyn set down notes about his activities – travels, meetings, observations – in the spaces in his printed almanacs, ‘in imitation’, he wrote, ‘of what I had seen my father do’. Printed almanacs were hugely popular texts in the 17th century, full of useful information, like detailed monthly calendars; descriptions of local fairs and journey routes; chronologies of history; astrological, medical and agricultural notes; a ‘zodiacal body’ anatomizing the influence of the planets on parts of the body; and ‘predictions of weather, and strange events.’ The printed almanac is at the absolute peak of its popularity during Evelyn’s life-time, and he used it, as others did, as a kind of framework for making his own diary notes. Here is Evelyn’s almanac annotation for July 1637, entered, the handwriting suggests, close to this date, in his copy of Thomas Langley’s A new almanack and prognostication (1637).

The very scratchy hand on the right, written against July 2nd, records ‘A[t] oxfor I first Receued the holy communion being yn in Bal Coll Chap Mr Cooper preacht’. Evelyn is using the printed monthly calendar as a prompt, and as a space, to record his note. This note was a first, preparatory stage of what would later become Evelyn’s fuller, and today very famous diary: Evelyn converted these staccato early notes into expanded narrative prose, decades later, producing his diary not in a moment of immediacy, as we sometimes imagine, but through a careful process of noting and subsequent revision. The brief note about holy communion in Balliol College chapel is redrafted, some time after 1660, as this:

Upon the 2d of July, being the first of the Moneth, I first received the B: Sacrament of the Lords Supper in the Colledge Chapell, one Mr. Cooper, a fellow of the house preaching; and at this tyme was the Church of England in her greatest splendor, all things decent, and becoming the peace, and the Persons that govern’d.

The most of the following Weeke I spent in visiting the Colleges, and several rarities of the University, which do very much affect young comers; but I do not find any memoranda’s of what I saw.1

Less an unguarded, spontaneity record of a life, Evelyn’s diary emerges as a revised, retrospective, we might even say literary text.

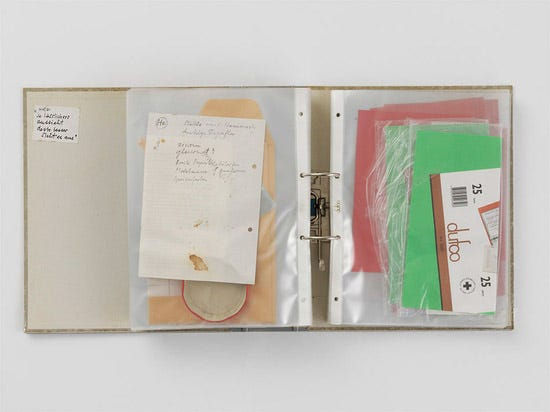

3. Dieter Roth (1930-98)

Dieter Roth worked on his first version of ‘Flacher Abfall’ (‘Flat Waste’) for a year, when he was 43: it’s the record of 12 months of Roth’s life, although it may not look like that. Roth gathered small, flat, seemingly worthless objects – each less than 1cm thick – that passed through his days: the kinds of scraps that would normally be discarded, like bottle labels, envelopes, handkerchiefs, jam jar lids, cigarette butts, pieces of paper, postcards, fruit peel. Roth stored them, in the spirit of a meticulous cataloguer, in plastic sleeves.

The sleeves were placed in binders which were filed on shelves. Roth continued to work on ‘Flat Waste’ for during his 50s and 60s, and produced 623 folders.

These collections register Roth’s continuing interest in collapsing the distinction between everyday life and the work of an artist: the index of waste becomes a register of Roth’s life. The French scholar of autobiographical writing, Philippe Lejeune, described the diary as ‘a series of dated traces [série de traces datées]’ which tended to be ‘[d]iscontinuous. Full of gaps. Allusive … Redundant … repetitive’ – and ‘made up of more empty space than filled’. In certain moments, Lejeune suggests, these accumulated traits produce ‘the feeling of touching time’.

Roth’s flat collection fits with this punctual, non-narrative conception of the diary. One effect of Roth’s ‘Flat Waste’ is to make us pause over and therefore dignify these superfluous objects. ‘I do not seem to be able to throw them away,’ Roth said, and in representing durational experience through discarded scraps of food and paper, rather than grand narrative events, Roth is pushing to the limit the connection between the diary and the everyday.

Pavel Büchler’s Idle Thoughts with a foreward by Maria Balshaw and an afterword by Adrian Searle, (Manchester: Whitworth Art Gallery, 2013).

Fiona Bradley, Dieter Roth: Diaries (New Haven, Conn.: Yale UP, 2012).

Philippe Lejeune, On Diary, edited by Jeremy D. Popkin & Julie Rak, translated by Katherine Durnin (Honolulu: The University of Hawai’i Press, 2009).

The Diary of John Evelyn, ed. E.S. De Beer (Clarendon: Oxford, 1955), 6 vols, vol. 1, pp. 19-20.

"‘I do not seem to be able to throw them away,’ Roth said, and in representing durational experience through discarded scraps of food and paper, rather than grand narrative events, Roth is pushing to the limit the connection between the diary and the everyday."

Yes, that's my excuse, too. Sadly, my partner isn't buying it.

Mike

With syntax like that how can Evelyn fail to be literary? Syntax is missing from the others, of course, which is one of their deficiencies.