From an auction house in Nottingham, I buy a series of 18 diaries running across the early to mid-20th century, kept by a man called Samuel who lived in a village near Chesterfield, Derbyshire. (I know his full name, and his dates, and can even see his house, in its current state, on Google Maps, but, to my surprise, it feels wrong to convey these specificities.) The diaries run from 1922 until 1959, although there are gaps. They provide the kind of punctual information we expect from the form – the noticing of daily things that would otherwise leave little or no record – but Samuel has a nice habit of reflecting on his own writing, and responding to the sense of the passing of time. I love durational writing – writing that, composed across a long stretch of time, has the effect of holding the passage of days and years.

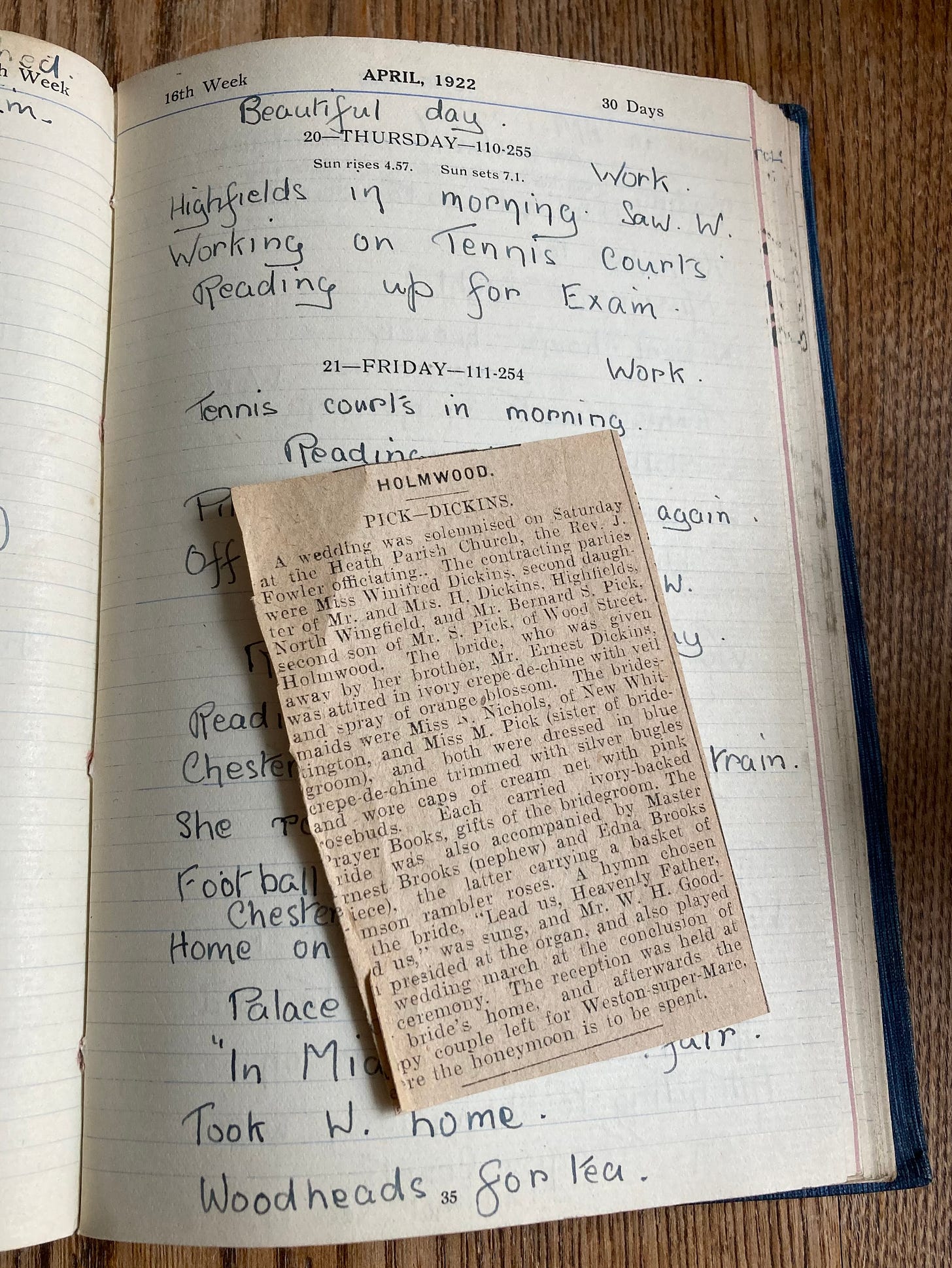

They begin in 1922: the year of High Modernism, a time when the British Empire lays claim to one-quarter of the world. In his village, Samuel reads a lot; stays late in bed; attends Sunday School; travels between the local towns by bus and train (‘Left Buxton 9.55 pm Home 11.45’); visits Williamthorpe, Heath, Highfields; takes part in Amateur Dramatics; plays tennis; goes to Highfields for tea; attends football matches and records the score and attendance (‘Huddersfield 1 Preston 0 English Cup Final 53,000’); notices the weather (‘Very cold’; ‘Beautiful day’; ‘Rough’); notices gardens (‘Tulip bed a picture’). He records local news: ‘Lad killed in H’wood, Blackshale.’ ‘E. Chambers bought new Yorkshire Terrier.’ He has a haircut.

Here he is, in the first week of January 1922:

Samuel also tips in cuttings from local newspapers, like this one, describing his own wedding that year:

The last diary I have is from 1959. Is he the same person? One kind of doubling that diaries achieve is the sense of a self that is recognisably the same, but simultaneously a self that is developing, altering, inconstant. Another doubling is a sense of time: of time as duration, an experience of onwardness, but this unfurling held in check by the shocking suddenness of the particular record, whose effect is to shudder things to a halt. ‘Took the bathroom tap to pieces and made it easier to turn: Not before time.’ The great scholar of diaries Philip Lejeune identifies the particular power diaries have is ‘the feeling of touching time’, and we can feel that here, as Samuel tinkers with the tap in his bathroom on a day in December, 65 years ago.1

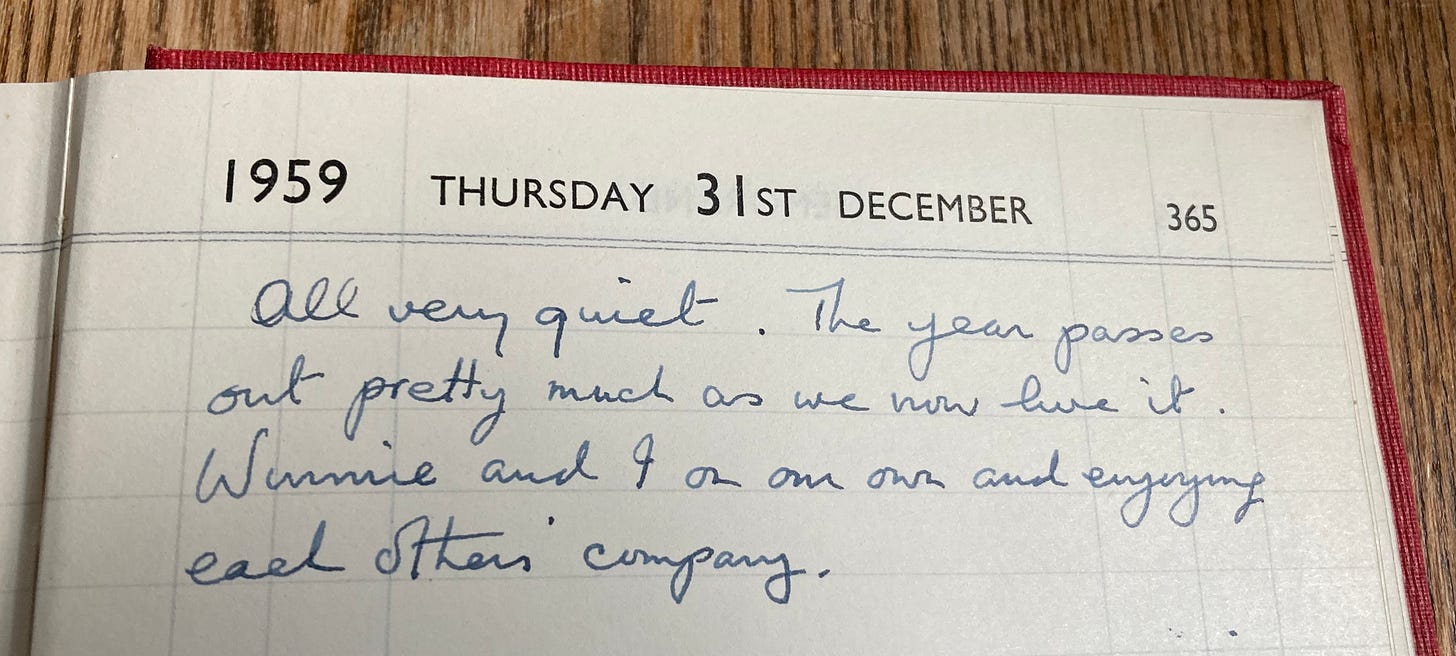

People enter Samuel’s diary, sometimes for a single record; sometimes for a while; they leave with no fanfare, or they die; and very occasionally, across the whole run of texts, they remain. The girl he knew as ‘W.’ in 1922 – ‘W. met me at Kirkby station’; ‘W. made shirt for me’ – is now the wife who, usually still recorded as ‘W.’, holds Women’s Institute meetings in the living room, and ‘had a hard day washing’. Time is speeded up. ‘Winnie and I went to Heath and changed the flowers on the graves.’ There are constants in terms of what Samuel notices (‘Awful weather’; ‘Hair cut’), and also in Samuel’s pleasure in living – his lunging at things. ‘What a life! Bolsover for lunch.’

This is the last entry I have, from 31 December 1959:

Philippe Lejeune, On Diary, ed. Jeremy D. Popkin and Julie Rak, trans. Katherine Durnin (Honolulu: The University of Hawai’i Press, 2009), p. 209.

It is as if we can replace the bathroom tap with the concept of 'time.' We take time to pieces, making it easier to handle or ‘turn.’

The final entry also offers a beautiful self-reflexive ode to time; it correlates with the way we live it.

This is charming. I love how fresh the pages look. The difference in Samuel's handwriting over the period of 37 years. The inclusion of the cutting about his wedding and the fact that W is still there in the final entry. The simple details and the fact that they end on a simple note.