Books Going Wrong

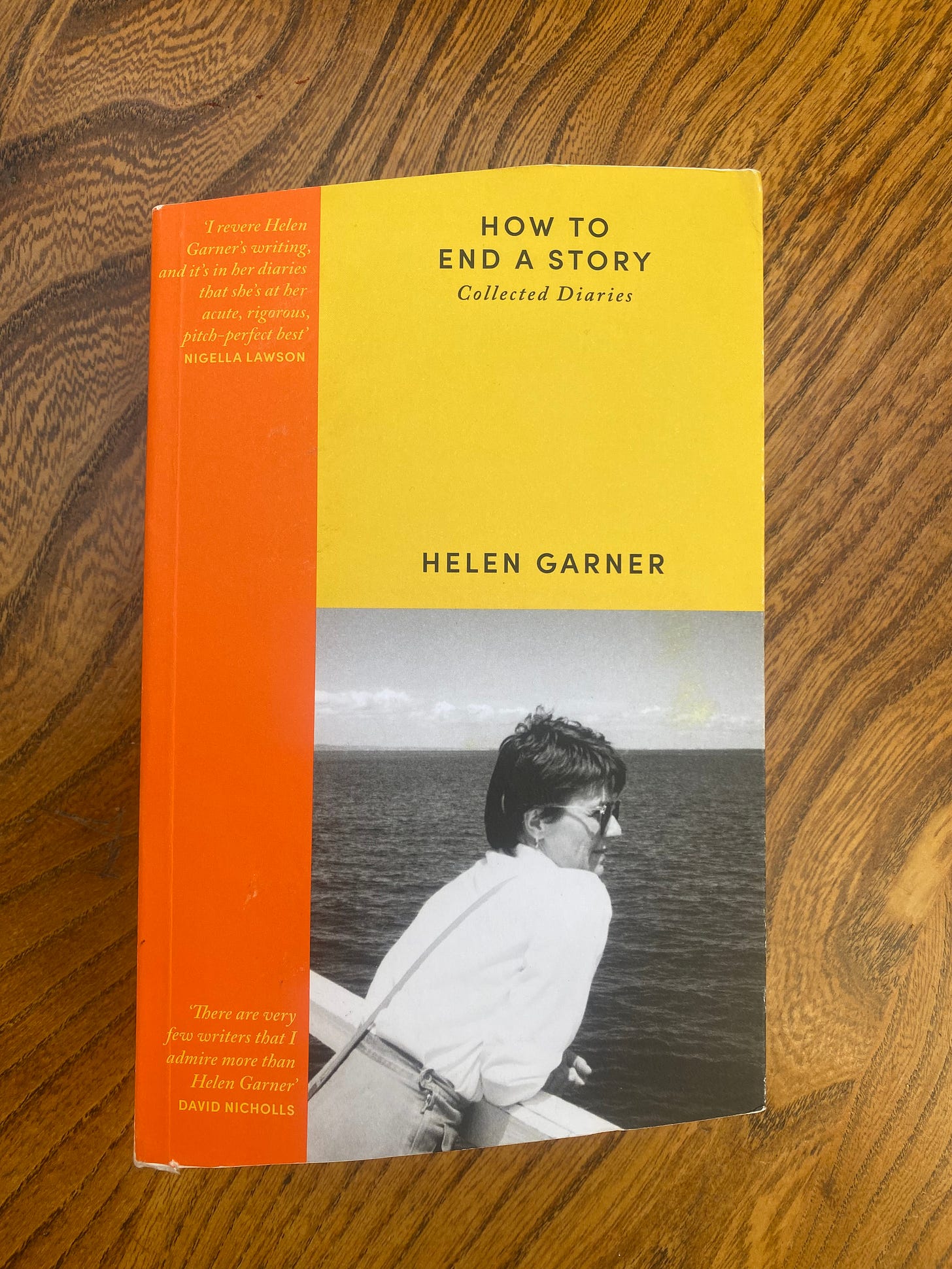

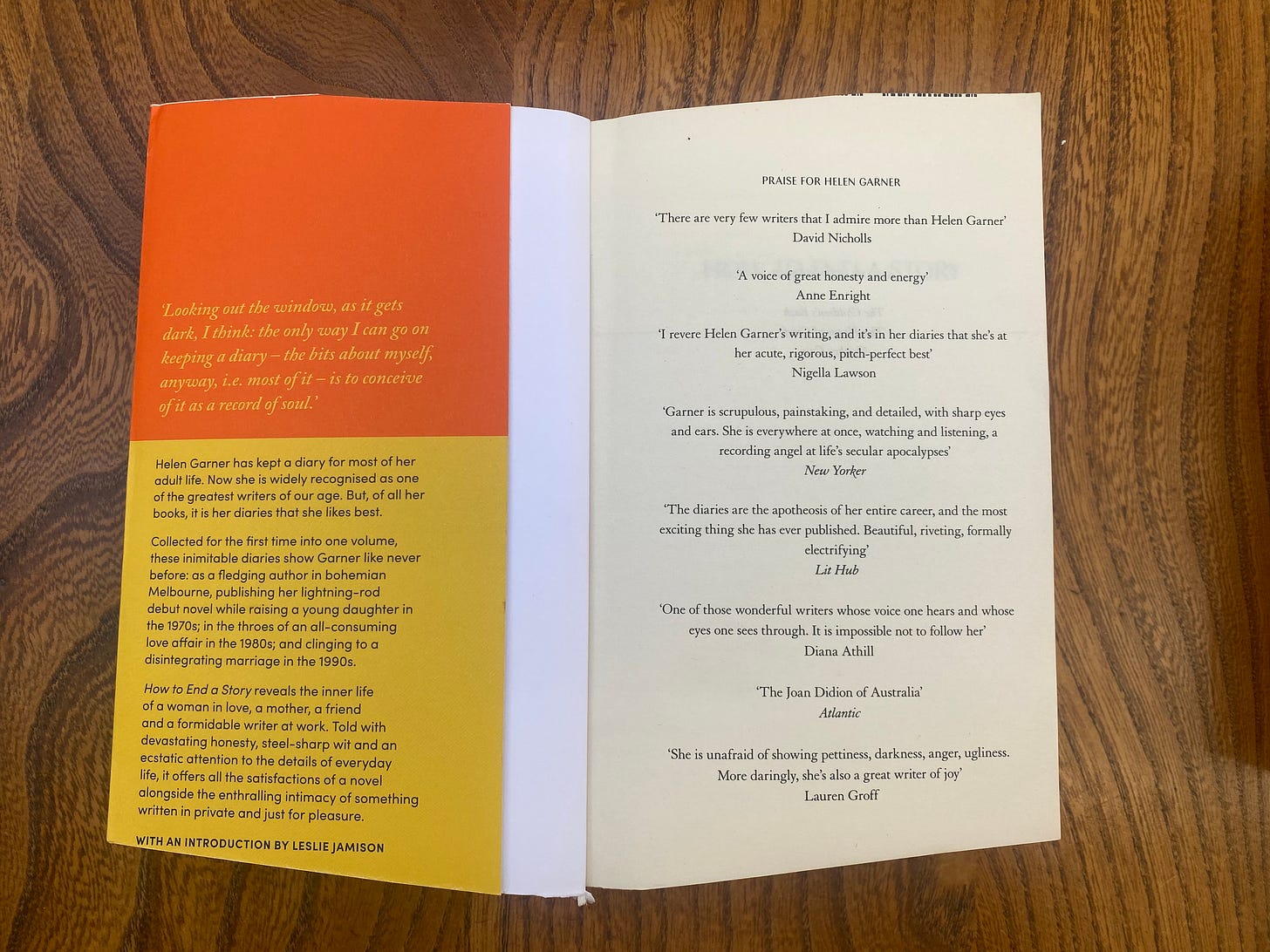

My friend Lottie sent me a copy of Helen Garner’s collected diaries, How to End a Story, for my birthday. It’s riveting: the false starts and self-doubts of a writer in the process of becoming brilliant. When I opened up the wrapping, the book that emerged had an off-kilter quality that I immediately liked.

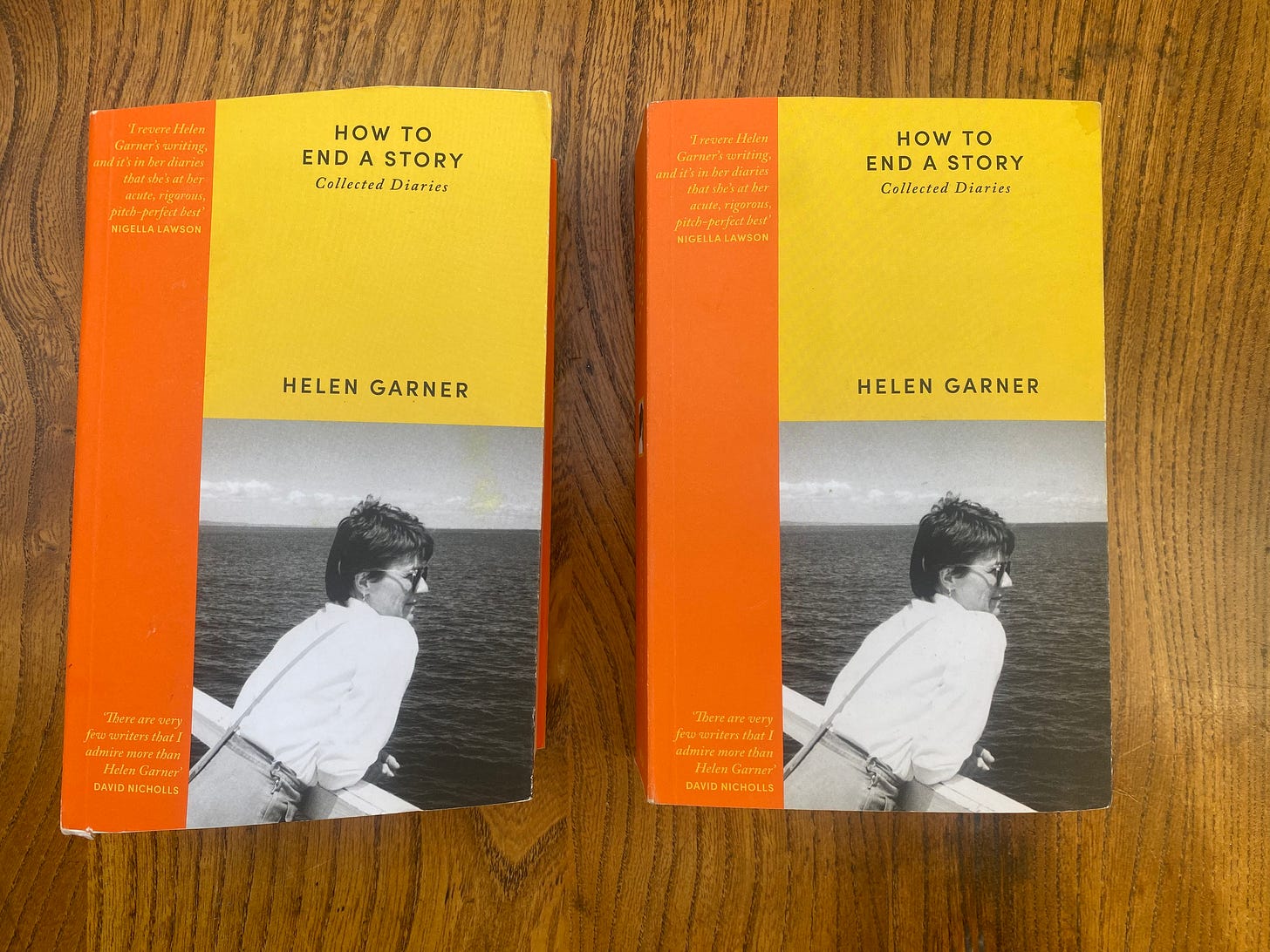

The bottom and top edge of the text block and cover had been cut at an angle, producing not the tidy rectangle we expect, but something slanting and irregular. None of the inside text was obscured, but the text at the bottom only just gets squeezed in. The whole things feels perilous.

Was it meant to look like this? I didn’t think so, and comparing Lottie’ gift with another copy brought into focus the nicely hacked-about nature of my birthday present.

Interesting things happen to objects when they go wrong.

The first is that the object’s materiality comes into focus – the fact of it as a bundle of stuff (rather than bodiless, transcendent ideas) is felt. The TV remote that stops working is suddenly more vividly a plastic and rubber thing we hold in our hands and stab with frustration, rather than the object made invisible from its sleek efficacy.1 So with the book: the book is a thing of paper and glue and stitching and ink – and also of edges and lines – and of roughness and texture – when it goes awry.

The second thing is that in these moments of wrongness we imagine the book’s process of production: a book mistakenly trimmed (if that’s what my present is) probably makes us think about what went awry, makes us speculate on process, and so our head is suddenly in the printer’s, at Clay’s, in Bungay, Suffolk, pondering presses and conveyer belts. Our imagination isn’t transported in this way with a tidy finished volume. So we might imagine the book clamped to a conveyer built, and two parallel guillotine knives descending to trim the top and bottom of the book, and then a third knife perpendicular to the first two trimming the fore-edge. (You can see something like this happening here – jump to about 50 seconds. It’s hypnotic: I could loop this and watch it for hours.) My copy must have been not positioned squarely as it hit the trimmers. Normally, a copy like this would be binned, but thankfully this one made it through.

Thanks to Dennis Duncan, Paul Nash and Richard Lawrence for talking to me about trimming; to Clay’s, in Bungay, Suffolk, for answering my questions; and to Lottie for the present.

A bit conspiratorial, but considering the two parallel guillotine knives from Bruno Latour’s perspective reveals them as active agents rather than mere objects. Their off-kilter—possibly intentional—trimming distorts the typical separation between "subject" (you) and "object" (the book), shaping both into a network with new connections and nodes.

Omg!!! How exciting to have such a one off! I’m in Australia so have the three volumes separately but also bought the uk combined version (because why wouldn’t I) mine sadly is not as impressive as yours