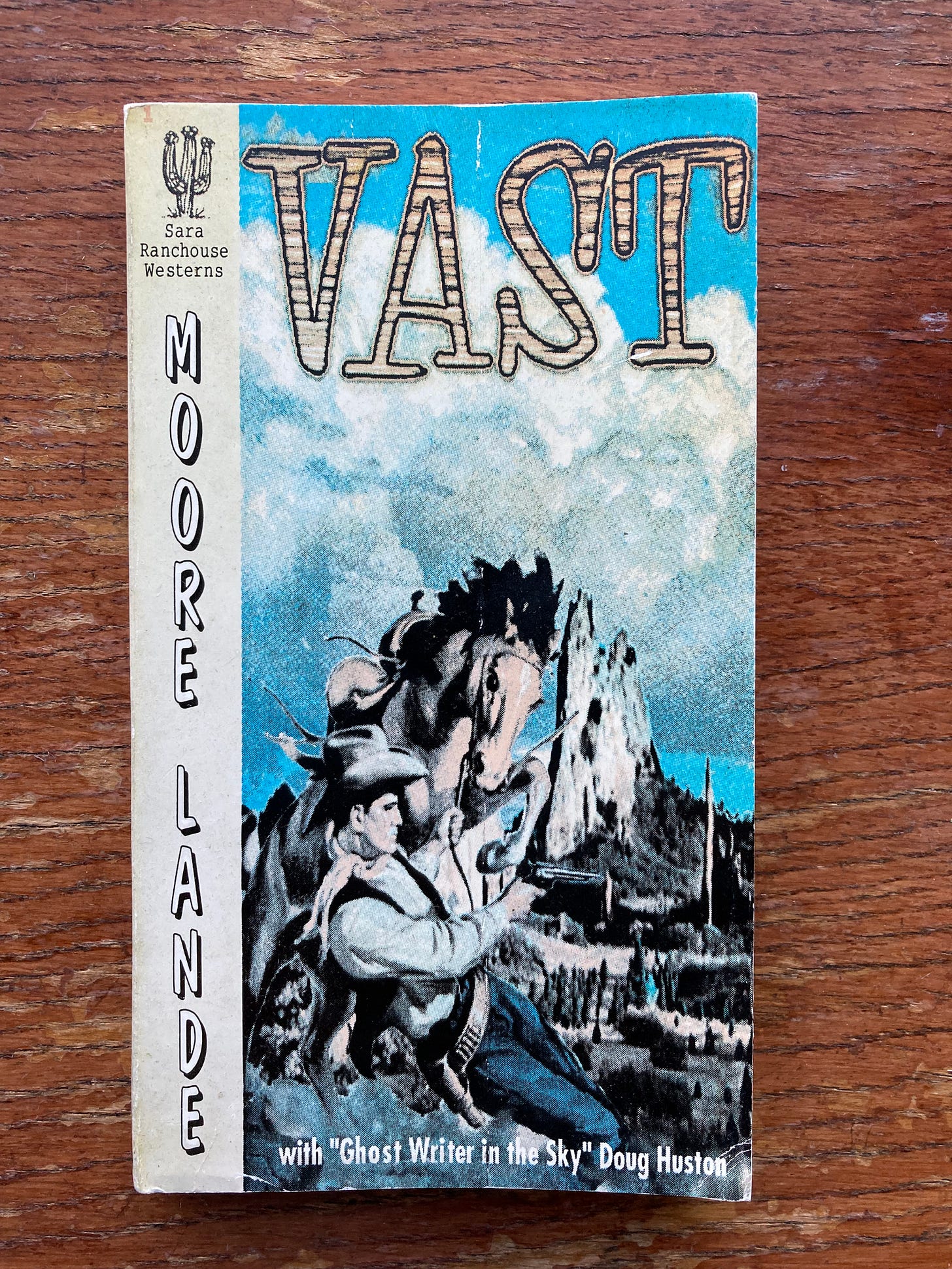

I’ve been enjoying reading Vast (1994) by Doug Huston. As Huston’s punning pseudonym ‘Moore Lande’ suggests, it’s a Western, and the author glories in his book’s pulpy conventions. ‘Ahead of him lay danger-bullets and fists. Ahead of him lay trouble with the only girl he really cared about.’ The subtitle is ‘an unoriginal novel’, and when we begin to read we notice immediately that each sentence is pegged to a footnote. Here is the opening.

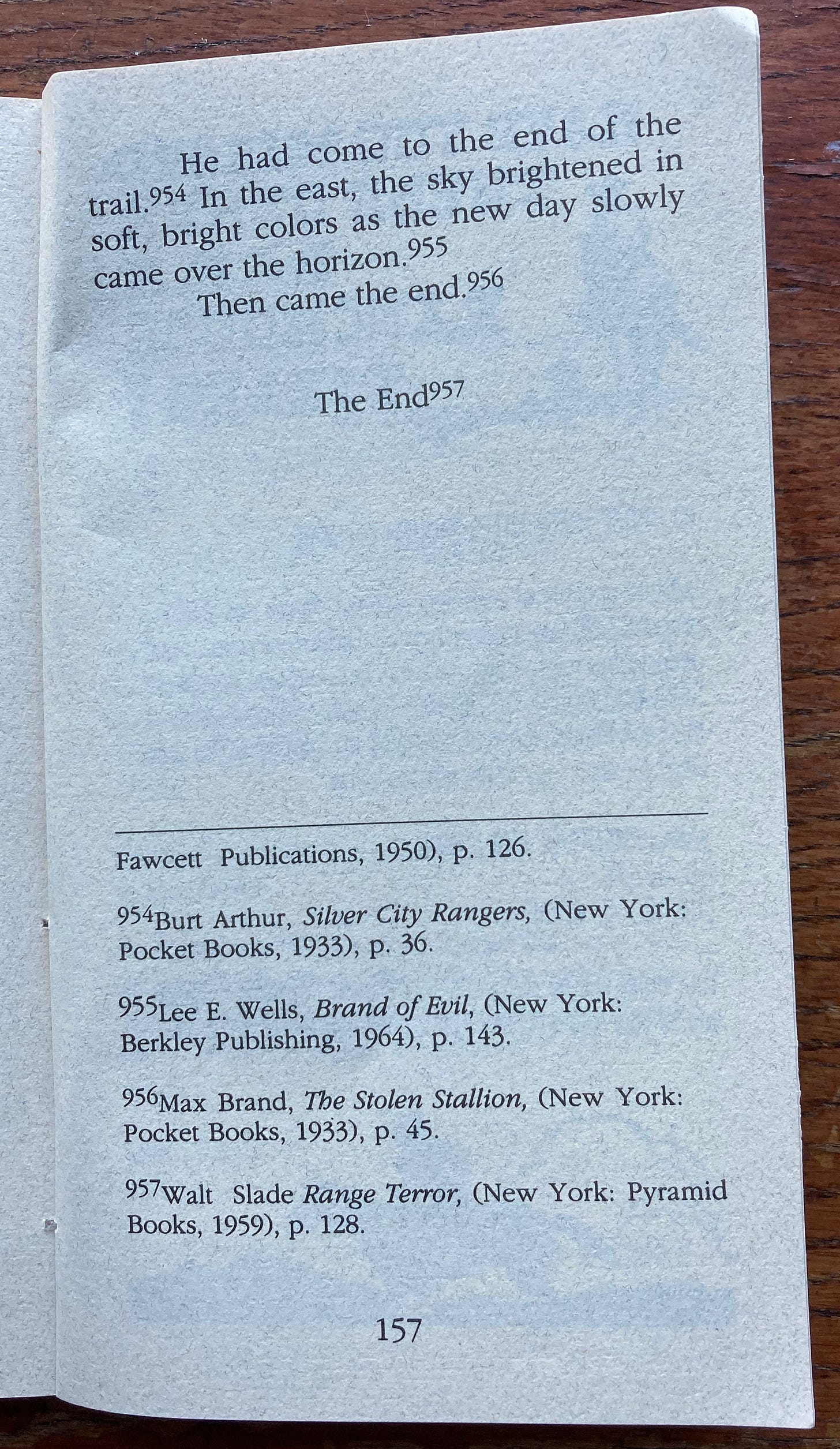

This is a Western novel composed entirely of individual lines appropriated from other Western paperbacks, with the citations included. The unit of creativity is the sentence: this is the scale at which Huston ‘writes’. Vast tells a story of the travels of a hero, rather wonderfully named ‘Dave Moore’. We see him constantly ‘racing forward’, his eyes ‘raking the desolate scene’. My favourite passage is the very end:

One effect of this total dependency on prior texts is that the book, in being so loyal to convention, ends up being strange. It is too conventional to sound like the other books it copies. As Huston – or Lande – or the rearranged fragments – writes of the plot: ‘It is the story of a man who managed to be part of all of it … but never belong to anything, or anybody, but himself.’

In Woman’s World (2005), Graham Rawle began by writing a novel in the usual way: thinking up a story, writing the text. Once he had a draft, he began to search through hundreds of women’s magazines from the 1960s for portions of text – sentences, phrases, single words – that came close to his written narrative. Rawle would replace his original writing with these found passages. Often the match was not exact, so Rawle would approximate, and the shape of the story would be modified. ‘Little by little,’ Rawle said, ‘my original words were discarded and replaced by those I’d found.’ Using scissors and glue, Rawle assembled the pieces into a whole story of cut-out words. Where Doug Huston’s Vast signalled its sources via footnotes, Rawle gives us not references but the actual cut passages (or at least reproductions of them). The cadences of women’s magazines from the 1960s is still clearly audible, but the story is a new one.

Here is the first page. Look out for ‘Deep Gloss’, and also ‘Roy’.

In the 1630s, the Anglican community at Little Gidding, near Cambridge, led by Nicholas Ferrar, used scissors and knives to slice up printed copies of the gospels in order to reorder the text and harmonise discrepancies in the account of Christ’s life: cutting and reordering was here a means to obtain a single, harmonised text. The cutting and pasting was mostly done by Ferrar’s nieces Anna and Mary Collett. You can see the kind of thing they produced here:

Words from printed copies of each of the gospels are snipped out, combined, and glued in place. These harmonies combine the methods of Vast and Woman’s World. The text is cut and glued and so we are reading not transcriptions but the actual pieces of paper that have been excised, ordered and pasted down – in this sense, Little Gidding and Rawle are engaged in similar projects. But Anna and Mary Collett have added superscript letters at the start of each sentence, or phrase, or word, that signal the source Gospel, rather as Huston’s Vast gives us those footnotes: the ‘Mr’ at the start signals ‘Mark’. The ‘L’ – for the single word ‘Now’ – indicates Luke. ‘M’ is Matthew. This is a harmonising, a cohering of fragments, but it also acknowledges the original placements and so imagines the possibility of putting the words back. This is why these lavish folio harmonies have the qualities of both finished magnificence, and in-flux contingency.

Reads like the start of a book on the boundaries of pastiche and collage. Wonderfully observed!

Interesting that St. Jerome has a codex in his right hand, but what looks like the makings of a bookroll under his left hand, on the table. I expect it was a sheet for one of his letters, cut from a papyrus or parchment roll. Jerome lived right at at the point where the roll gave way to the codex; Jim O'Donnell says Augustine for example, probably never saw the holy books combined into a "bible."