My book, The Book-Makers, (which is a book about books — published in book-form) is out in America in 11 days. The cover is different (more 16th-century), and the word ‘Remarkable’ has been pruned from the UK subtitle (‘A History of the Book in 18 Remarkable Lives’) — but the rest is the same! In anticipatory celebration, I’d thought I’d ping out a section from the final chapter: chapter 11, on ‘Zines, Do-It-Yourself, Boxes, Artists’ Books’, which brings book-making up to an anarchic contemporary. Part of this chapter is about Laura Grace Ford’s brilliant Savage Messiah, which I really enjoyed reading and thinking about. So here is a slice of that: I hope you enjoy it! References and links at the end, as podcasters like to say.

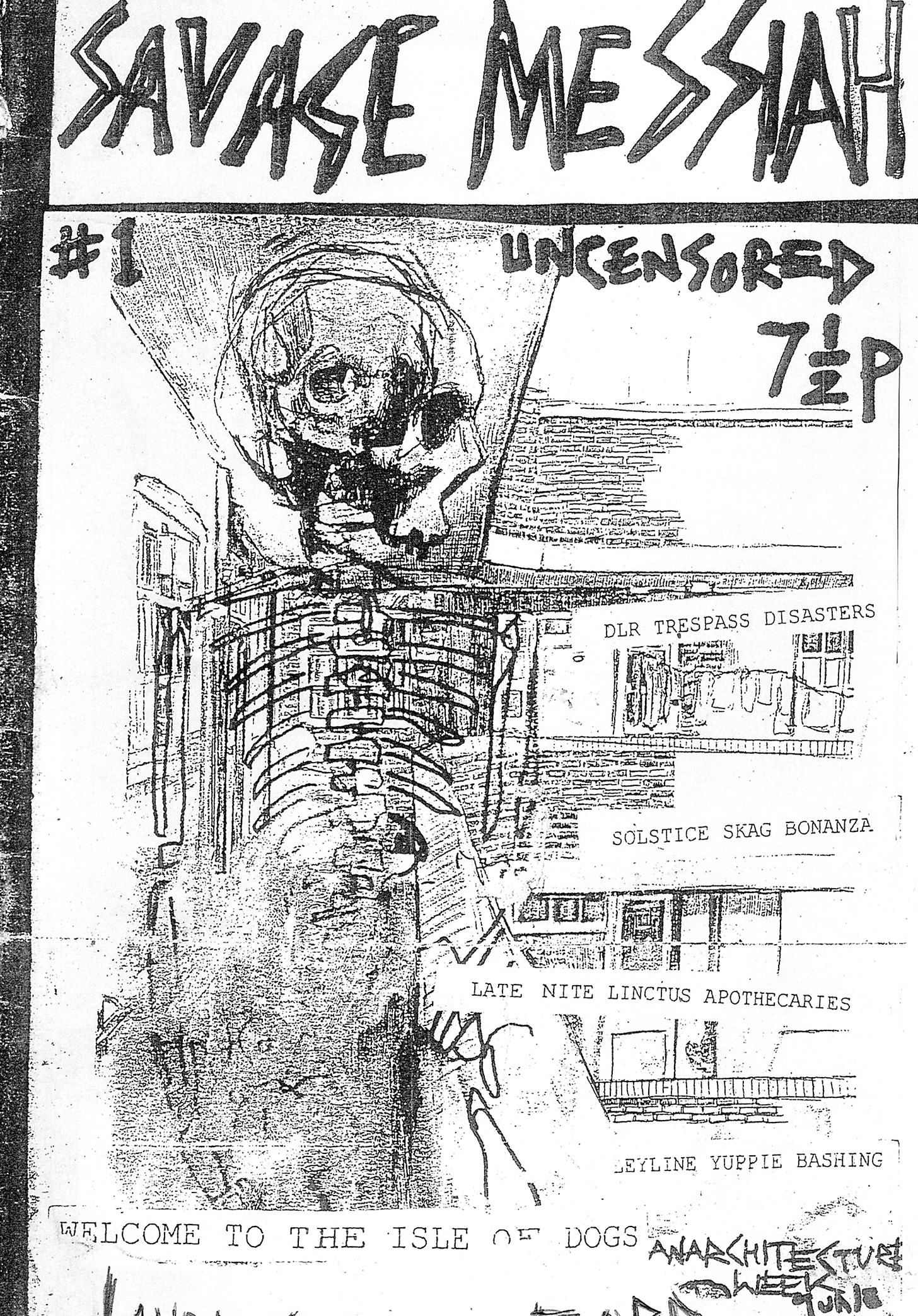

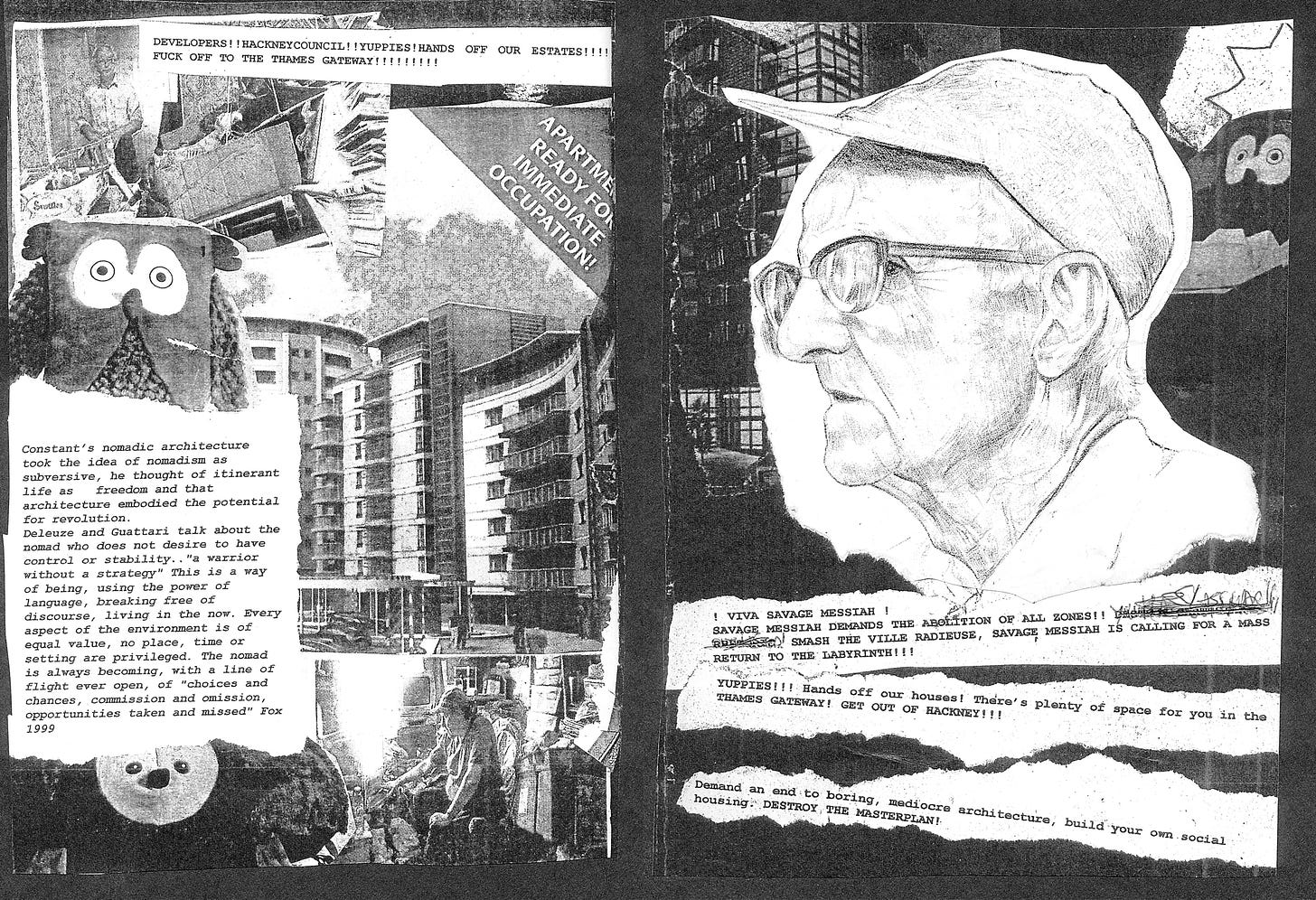

In 2005, around the time when London was awarded the role of hosting the Olympics in 2012, Laura Grace Ford (writing as Laura Oldfield Ford) began making a zine – for now let’s take that term to mean a self-published, self-distributed, non-commercial little magazine – called Savage Messiah. Like most zines, Ford’s was a product of photocopiers and of informal hand-to-hand distribution. Rather as Anna and Mary Collett in the seventeenth century had sliced up gospels to make Biblical Harmonies, Ford used scissors, knives, and glue to reorder the printed materials around her. And like her book-making forebears at Little Gidding, Ford’s work was ideological, although it was leftist political activitism, rather than Anglican piety, that her zines expressed. Across 12 editions, Savage Messiah recounts a series of walks or ‘drifts’ through London that stand in direct and confrontational opposition to what Ford saw as the destructive, neo-liberal modernising of the city, a process she associated with the Blairite government and, in particular, with the looming Olympics. Issue 2 (‘Welcome to Elephant and Castle’) has text juxtaposed with black-and-white photographs of ruined buildings: ‘“Young professionals” sit outside gently conversing in sympathetic tones. The translucent edifices of Starbucks and Costa become shimmering promenades.’ Another image proclaims: ‘HANDS OFF OUR ESTATES!!!!’

Different kinds of text collide in each issue within the descriptions of Ford’s ‘drifts’ across the sites of demolished buildings, or crumbling high streets, or along the routes of subterranean rivers: drawings of places and people Ford knew; photographs of the city’s architecture (graffitied walls, tower blocks, stairwells, shop fronts); maps; advertisements from estate agents and fliers from Reclaim the Streets; and diaristic accounts of drinking sessions in pubs, fights, sex with strangers, of traveller sites and squatter communities. Ford’s zines are shot through with quotations from authors and philosophers (J.G. Ballard, Italo Calvino, Samuel Beckett, Thomas De Quincey, Charles Baudelaire, Walter Benjamin) who help Ford understand what is happening to London, the displacement of working class men and women amid corporate land-grabs, and how the capital might be saved. Each edition takes in a different slice of the city – the Isle of Dogs; Elephant and Castle; Marylebone Flyover; the Lea Valley; Acton and Camden; Dalston and Hackney; Kings Cross; Heathrow – and as Ford recounts her movements, her words and images also move back and forwards in time (it’s 1973; it’s 1981; it’s 2006; it’s 2012). Earlier moments of political rebellion or resistance are summoned up, or glimpsed like ghosts: ‘a perambulation through the shadowscapes’, Ford calls it. This combination of textual fracture – of pieces gathered and recombined – and a movement through space and time creates a warping, dream-like world where the reader experiences different points in time simultaneously. The effect is to release a sense of the city’s radical possibility, to revive a politically resistant past, and to propose an alternative to a London that is, in Ford’s conception, gentrifying, banal and indifferent to its own actual history.

Ford produced 11 editions, and the zines were also later collected together in book form and published by Verso in 2011. In June 2018, after the fire at Grenfell Tower in June 2017, Ford produced a special single edition that returned to this area of London, placing the fire in a long history of middle-class gentrification and local government neglect of the working classes.

Part of the power of Savage Messiah as it appeared as a flimsy, Xeroxed zine was precisely its non-bookishness: its acquired mobility and political charge from its form. The vibrant presence of non-books is a vital strand running through the history of print, from the indulgences printed by Gutenberg in the 1450s through Franklin’s jobbing print work. When I spoke to Laura Grace Ford, she described her decision to write serial zines, rather than a conventional book like a novel, as a consequence of her life at that time in 2005.

I was living on a housing estate in Hackney – we were living in short-life housing. And we were being evicted. And so the zine was inextricably tied to that, really. So that sense of the ephemeral or things being made quickly or that sort of transient quality of it – it actually was practical as well as aesthetic. Because my resources were limited. And I did photocopy things at work, because I used to work for Westminster Council teaching day centres and homeless shelters. And I used to just photocopy a few, a few zines in the office, and literally the first editions of them would be maybe 20, 30 copies.

The zine format was an expression of Ford’s sense of distance from any kind of cultural centre – ‘it wasn’t like I had a choice, it wasn’t like I had access to the publishing world’. Ford had little sense of a wider readership: ‘I was living on this estate, and my audience was my mates and fellow activists. I had absolutely no idea that it would ever be taken up by an academic publisher and turned into a tome. I would have been too frightened to write anything.’ Ford organised nights at venues such as the Foundry in Shoreditch, a bar and space for art performances established by Bill Drummond of the band The KLF – ‘it was quite anarchic and the activist element was always present’ – and copies of Savage Messiah were sold there or handed out. Number one cost a parodic ‘7½p’; later editions were £2 or £3. The zine entered the world as one component of a wider celebration: DJs, and music, and drinks, and ‘it would often involve a walk as well, or some sort of trespass.’ It was a noisy birth. The printed text here, was an event, or part of an event – a publication in the literal sense of being made public – and something is no doubt lost when, years later, the music has faded and the drinks have gone and we sit reading copies of Savage Messiah in special collection libraries or on silent screens.

By the time Ford started writing Savage Messiah, there was a long history of zine writing that found one origin in sci-fi fanzines of the 1930s such as The Comet; gained popularity in the punk scene of the 1970s with Do-it-Yourself, photocopied publications like Sniffin' Glue, Search and Destroy, and, slightly later, from 1982, Maximumrocknroll; and boomed in the early 1990s with feminist and queer zines, particularly those associated with the Riot Grrrl movement, such as Bikini Kill, with an accompanying band of the same name started in 1990 by Tobi Vail and Kathleen Hanna. As the scholar of zines Janice Radway has written, the ‘unifying thread’ of zines ‘is their outside-of-the-mainstream existence as independently written, produced, and distributed,’ and the potential they offered often marginalized communities to articulate or visualize their stories. Riot Grrrl zines like Discharge or Wrecking Ball defined themselves in opposition to a mainstream media dominated by a small number of global conglomerates and understood to be exclusionary, repressive, and technocratic. Of course, the tendency of capitalist culture to appropriate and commodify precisely the cultural forces that seek to oppose it complicates this idealism – as when, in Ford’s words, in 2006 ‘you could go in a Top Shop or somewhere like that, and there'd be T-shirts’ designed with a post-punk aesthetic, neutered of any political intent. But the utopian energy of many zines is real, even if the effects in the world are more complicated, and compromised. The Riot Grrrl zines of the 1990s, for example, continue to inspire later publications, like the Oxford-based intersectional feminist zine Cuntry Living which has flourished since 2014. ‘Like our sisters before us,’ write the editorial collective in the first issue, ‘we wanna talk about the problems women face in our society: endemic sexual abuse, economic discrimination, objectification and slut-shaming.’

As objects these zines are (Radway again) ‘nothing if not motley’, offering a patchwork of word and image; defying any ordered, linear reading; and possessed of ‘a kind of uncontainable, ecstatic generativity.’ The poet John Cooper Clarke catches things nicely when he writes of Mark Perry’s Sniffin’ Glue (1976-7): ‘with its cheapskate house style and semi-literate enthusiasm … there was a piss-or-get-off-the-pot urgency about the whole production.’ Zines might reprint and collage copyrighted images and play with format in a dance that is a continual mockery of the conventional bound book. Mark Todd and Esther Pearl Watson’s Whatcha Mean, What’s a Zine? (2006) presents instructions for zine formats they call standard ½ page; no staples; ¼ page mini; accordion; stack-n-wrap; freebie; micro- mini; and French fold-n-bind. ‘Break out of the format!’, they urge, before listing ‘Places to leave your zine’ – bus stops, libraries, car windshields, concerts, copy stores, ‘places where people sit’, or ‘any public place’. Zines make it clear how easy it can be to publish: on a fundamental level, that is their message – you can do it, too! – and this commitment to democratizing, rather than mystifying book-making, is central to the zine as a form. In this sense, zines stand as polar opposites to the technical and aesthetic mastery of a book-maker like Thomas Cobden-Sanderson: the calligraphic flourishes of Edward Johnston, and Cobden-Sanderson’s baffling way of talking about ‘the Book of Life’ (before things went pear-shaped and he dropped his type in the Thames). All of that might prompt admiration but to finish a Doves Press book is also to feel, I could never do that – and that was surely Cobden-Sanderson’s aim. Zines encourage readers to become D.I.Y. makers, rather than stunning them into silent or baffled consumerism, or connoisseurship, or study; zines are a spiky riposte to a book-making culture that is seen as corporate, consumerist, profit-seeking, and commercial. In the age of the Internet, many zines became e-zines or webzines, but many did not, and persisted defiantly with older forms of book-making at the very moment when digital and online publication offered a more obvious route: rather than the blog, paper and pen, scissors and glue, staples and thread.

Ford was certainly conscious of this zine genealogy – ‘I was aware that I was channelling this kind of post-punk aesthetic’ – although there were other cultural coordinates, too. The critic Mark Fisher saw a comparison between Savage Messiah and 1980s mix tapes – compilations of music from multiple sources produced by listeners on cassette, often with a contents list scrawled in biro – as works that proceed through the jolt of juxtaposition. This link between zines and music is important for Ford, and she imagines reading Savage Messiah as a kind of listening.

You can’t read it, like from start to finish the way you would a novel. I don't think it really makes sense like that. I feel like, you can zigzag across it, you know, in different routes. I remember in the introduction to A Thousand Plateaus [(1980)], [Gilles] Deleuze and [Félix] Guattari talk about how you should read that book, like listening to a record. You know, you can like move between tracks, some tracks that immediately resonate with you and some that you don't like, and some are a slow burn. And you can, you know, it doesn’t have to be like, linear. I like that.

The physical quality of the zine is central to the achievement of Savage Messiah, and it matters that this is a physical as opposed to an online publication. In 2005, blogs were increasingly popular – ‘loads of people I knew were doing blogs’ – but Ford felt the urgency of the political context demanded a form of publication held in the hand, turned over, passed around: ‘I felt because of this encroachment on public and communal space, it was really important to do a physical zine that could be a kind of catalyst that would galvanise these collective moments.’

The D.I.Y. materiality of the zine – that sense that it is the product of the bedroom, not the office – is crucial for this sense of animating different moments from London’s past, for ‘rupturing the veneer’, for feeling the power of glitches or gaps in the official history of London: ‘being able to cut and paste these different elements, and juxtapose things that may be kind of jarring to produce unexpected results.’ Savage Messiah was a response to Ford’s sense that ‘neoliberalism was imposing an official text of what London was … that culminated around the Olympics’, and her zine’s cheapness, ragged ephemerality, mobility, and immediacy meant ‘it could just like pop up in the cracks … in these other pockets that persisted, despite that onslaught.’

Ford was familiar with the cut-up-techniques of William Burroughs and a wider tradition of modernist collage, although her familiarity with these came first not through galleries or books but, as a young teenager, via record sleeves. The Xerox machine is also central to Ford’s work, and in particular its capacity to bring together into a single flatness excerpts and pieces from diverse sources:

What I always loved was the magic of the photocopier. So you can have all these disparate elements and it’s all messy and uneven, and the splotches of glue and wrinkles in the paper, and it’s drawing on different temporal zones, but as soon as you photocopy it, it’s all smoothed out, isn't it? And then they all coexist seamlessly. So you're kind of referencing those jarring moments, but the overall effect when you photocopy something’s more that things coexist more seamlessly.

In 2005, Ford had little thought of literary posterity, or of the zines as collectible in the longer term. Today, she hasn’t even got copies of all the editions herself and ‘when Verso came to publish it as a book, I had to put a call out to see if people could lend me them back.’ The sustained appeal of Savage Messiah beyond the small circle of friends and activists for whom Ford first wrote (‘there’s a lot of in jokes and a lot of ludicrous stuff’) is, Ford thinks, because the problem her zines attempted to address still pertains:

I think the reason Savage Messiah resonates with people is because you know, I feel like there’s so many people that have been expelled and evicted from London that are no longer part of the discourse. Or like the contemporary discourse around art. I feel like there's a lot of voices that have been marginalised, geographically and, you know, on every other level as well, and that sort of discontent, I mean, it smoulders, doesn’t it?

You can buy the (paradoxically) bookish edition of Laura’s zines in the Verso edition of Savage Messiah here.

For zines, the most recent work is Gavin Hogg and Hamish Ironside, We Peaked at paper: An Oral History of British Zines (Boatwhistle Books: London, 2022). Janice Radway has written some of the sharpest pieces on zines, including ‘Zines then and now: what are they? What do you do with them? How do they work?’, in A. Lang (ed.), From codex to hypertext (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press; 2012), pp. 27– 47, and ‘Girl Zine Networks, Underground Itineraries, and Riot Grrrl History: Making Sense of the Struggle for New Social Forms in the 1990s and Beyond’, in Journal of American Studies, 50(1) (2016), 1-31.

The Book-Makers is — of course! — available in the UK and the US.

I used to enjoy rifling through the boxes of slightly damp paper in the back of junk shops around brick lane in the eighties and striking gold with some enthusiastic cut up making a statement. Great piece thank you.