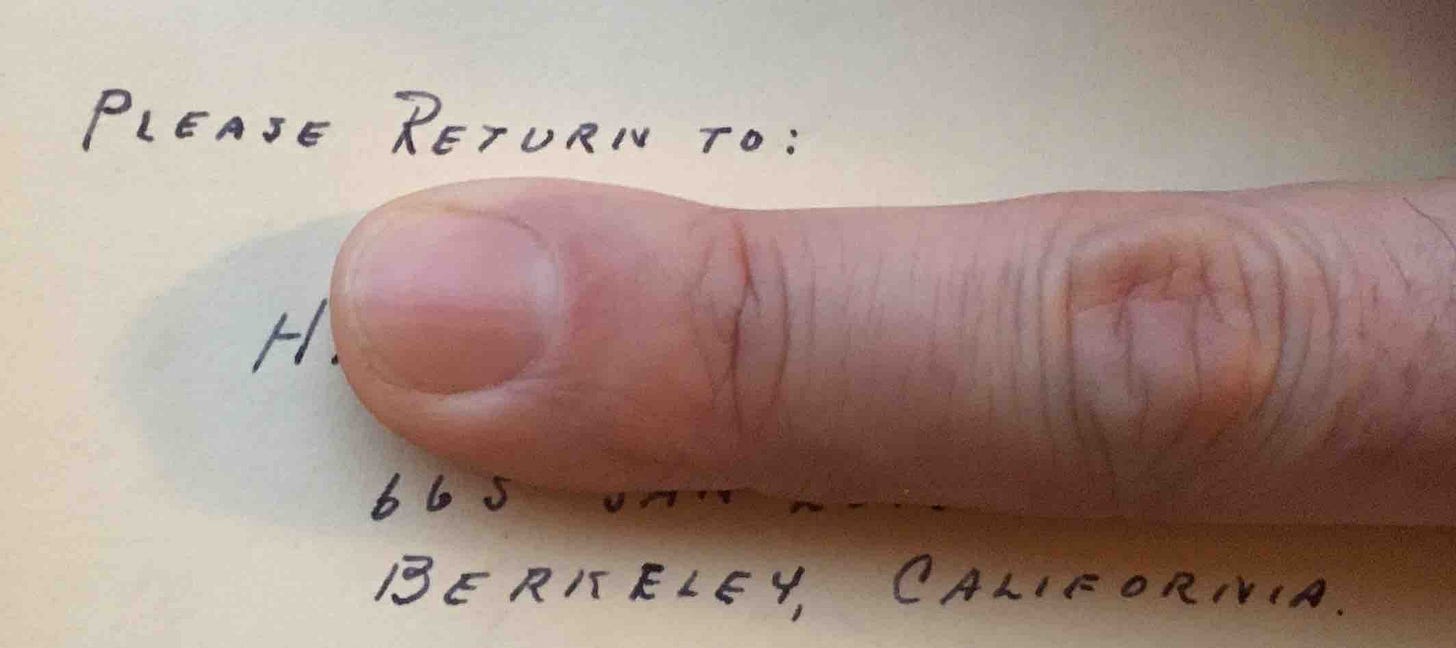

The diaries of H

In 2016, I purchased from eBay for £45 9 volumes of diaries owned by a clinical psychologist practising privately in Berkeley, California. The diaries cover the years 1950 to 1960 (1951 and 1956 are missing). Each volume is the same hardback format: The Daily Desk Diary manufactured by Books Inc, New York, described as ‘A Permanent Book Combining The Desk Calendar Pad, Personal Diary, The Business Diary, The Appointment Book.’ Each day fills a single page, and each volume measures 19x13cm: in the hand they have the weight and promise of a novel.

The name H ____ is written neatly on the fly leaf of each volume, along with an address on Piedmont Avenue, then (in 1953) on Telegraph Avenue, then (in 1957) on San Luis Road, and then, from 1959, Telegraph Avenue once again.

Almost all of the pages contain some kind of handwritten record. The handwriting is often illegible, or scarcely legible, and the impression is of notes made at speed with no concession to a future reader beyond the author himself. The overwhelming majority of these notes are surnames of clients, written against times of the day: Bradbury, Cann, Unwin, Davies, Mival, Lam. These names form the core of the 1950 diary. Progressing from volume to volume, particular names grow familiar, and then stop, and new ones appear: Ward, Ayres, Mayberry, Jones. Appointments tend to take place Tuesday to Saturday, although in later years Monday is used, too. In 1955 H tends to keep Wednesdays free. Appointments fall between 8am and 7.30pm. A busy day has 5; many days have 1 or 2; occasionally there are none. Sunday is always free. Client names are generally written in pencil, often supplemented with a neat cross (before) or tick (after) or (from July 1952) an inked asterisk, indicating, perhaps, attendance or payment. First and final appointments are noted (8 May 1953, 8am: Lloyd ‘last time’). The final page of each diary contains full names, addresses and telephone numbers of clients.

H is punctilious in recording non-attendance:

‘missed, no notification’; ‘cancelled on 30 min notice’; ‘on vacation’; ‘no phone call’; ‘didn’t phone’; ‘didn’t come’; ‘no show’; ‘missed appointment, but no notice’; ‘late cancellation’; ‘late call’; ‘overslept’; ‘cancelled at 4:20 because couldn’t get car from garage’; ‘just didn’t come’; ‘missed !!!’.

There are few records of costs although on 25 February, Unwin’s 10am appointment has the note: ‘cancelled because car trouble $5.00’, and some pages contain arithmetic which looks like money worries. A number of notes refer to the process of diary-keeping, particularly when noting has become problematic: ‘Book not [here] noted later from memory’; ‘No contemporary notation’; ‘o = retrospectively noted’.

The diary is in general characterised by haste, regularity, and reticence. It’s easy to describe it as unyielding, but that’s to import inappropriate expectations of candour: these volumes constitute the bureaucratic scaffolding around a series of professional interactions. But within this scaffolding there are moments, particularly in later volumes, when H writes short, delphic notes about his clients. A vignette opens before us, and we can briefly draw closer to something like a person. Here is one note, from 1 August 1953, relating to client French:

‘French – flunked like sch test. Gen. resistance – silly, nthg to say’.

What we read here is I think not H’s judgement, but a brief excerpt from French’s account of herself: H here is like an audience member at a theatre, scribbling a line spoken by an actor in his notebook. There was a moment – a few seconds in 1953 – when French described herself in these self-trivializing words. I’m silly. I’ve nothing to say.

There are other notes, for clients O’Brien, Cook, David, Parker, McCoy and Simon (1953-8):

‘O’Brien – General parasite – No MA thesis. Catholic bro younger, Explotive [sic] living– a girl, her ear. Draft — guilt. Takes sick leave from work’

‘Cook – has broken from g.f. New girl – really clear that sister enters into sex

inhibitions’

‘David – passive aggressive, F’s voyeurism, F’s death’

‘Parker – appearance, clothes, spank – couch, laughing at her, cheating her’

‘McCoy – late, anal, withholding’

‘Simon – Puts me on spot. “If anyone calls you – Let him sweat”.’

What can we know about these people? What do we want to know? H’s difficult-to-read handwriting records a blend of his own judgements (‘really clear that …’) with the briefly vivid voices of his clients. The self-lacerations of O’Brien (‘Draft — guilt’), and the controlled aggression of Simon (‘Let him sweat’), are audible, or nearly so, and if these diaries have a power, it lies not in a trespass into the private sphere, but rather in the spectral sense of voices from the past returning back to life. Sometimes the notes are short: ‘Webb – SILENCE’. Sometimes a client’s voice is embedded in H’s: ‘Bicknell’s “peculiar” qualities.’ Other annotations, unmoored from referents, are harder to understand, but have an urgent intensity as a result: ‘This is it’, written diagonally and then struck through; ‘and to feel justified’, underlined twice; ‘no no’ on an otherwise empty page; ‘Portia!!’ When H is sick, he notes it, usually in a loose blue pencil, expanded to cover the page.

The volumes also hold scattered scraps, letters, and items of ephemera, including a university parking permit, inserted loose at the start or end of volumes, or interleaved, or held to pages with paper-clips.

These loose letters contain messages from patients expressing gratitude at the moment of departure, writing of the need to end the course of treatment, usually for reasons of cost (‘the way I had to earn the money for therapy was too unpleasant’), or because they are moving, or because they have no time, often due to university studies.

Events from the outside world do not intrude: the Korean War, which began the year of the first diary, is felt only in the passing reference to O’Brien’s anxiety about the draft, and the presence of Joseph McCarthy, or Brown vs Board of Education, or I Love Lucy, or John Wayne, or the Russian space race, or Rosa Parks, or Elvis Presley, is impossible to discern. The only intervention from beyond is the word ‘SNOW’, written in large letters across 7 February 1959.

How did these diaries come to be for sale? Why were they not destroyed, or kept safely by someone close to H? I purchased them from an eBay seller specialising in ‘good quality new and vintage collectibles’: ‘champagne tastes for a beer budget.’ A lot of people want to read these kinds of thing: there’s a sizeable market online. With less of the spirit of rifling through old bins, the Great Diary Project collects, catalogues, and archives diaries, gathered through donation or purchase: it currently has more than 9,000 unpublished texts, ranging in date from 1785 to 2018, and although some are closed for a period of time (5 years, 40 years, 50 years, indefinitely), readers can consult many of the originals in Bishopsgate Institute’s reading room.

I wonder about the ethical position of what I’m writing. H’s diaries were written between 60 and 70 years ago; the author (certainly) and all of the mentioned clients (very probably) are dead – although some may have had children who are alive. I wrote a first draft with full names but then redacted H’s, and then removed the first-names of clients, and then changed the names of the clients entirely. There might still be sufficient information here for a determined reader to identify H, so my redactions may only serve to devolve the moral dilemma on to you, as readers. In making these omissions, I’m conscious that my article repeats not only one central dynamic of therapy – a promise of revelation that is deferred – but also the experience of the diary as a form: a hope for depth, intimacy, contact, that is never reached.

Brilliant piece Adam.