The Book-Makers - out and about

Hello Readers!

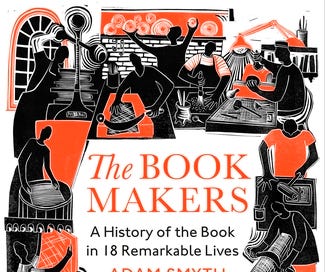

Two things related to The Book-Makers: A History of the Book in 18 Remarkable Lives …

First. I’ve a number of in-person events in the UK coming up about The Book-Makers, and I wanted to include the details here. Come along, if you can!

Blackwells, Oxford – in conversation with the brilliant Abigail Williams

Thursday 25 July, 6pm

Tickets and details here

Chiswick Book Festival, at Hogarth’s House, London

Monday 16 September, 7pm

Tickets and details here

Budleigh Salterton Literary Festival

Wednesday 18 September, 4pm

Tickets and details here

Wells Literary Festival

Saturday 19 October 5.30pm

Tickets and details here.

Second. I’m including below an excerpt from The Book-Makers — this is from the start of the chapter on paper. I hope you enjoy it!

Chapter 6. Paper

Nicolas-Louis Robert (1761-1828)

The man with the best claim to revolutionizing the paper industry died in something approaching poverty, in a village in northern France, on a hot day in August 1828. You won’t know his name. He was 66, and for many years had endured poor health working as a teacher in a primary school he had founded in Vernouillet. The pay was pitiful, but he passed quiet days with his wife and children. He wrote poems for his friends. He also spent – probably, surely – many hours reflecting on the arguments and the missteps: the ways he had been left behind. Nicolas-Louis Robert was ‘frail and ingenious’, as one historian has it, but also ‘broken and discouraged.’

What Robert invented, but spectacularly failed to profit from, was the technology that produced (in the words of its 1799 patent) ‘continuous paper’: that took paper-making out of the hands of the vatmen, couchers, and layers, and placed it on the rotating belt of a machine. Under the name of Fourdrinier, that machine was soon humming across European and north American factories, making vast quantities of paper, not as sheets but as loops of ‘indefinite length’, at speeds unimaginable to even the most brilliantly skillful of artisans who had made paper in Europe since the 12th century, in the Islamic world since the 8th, and in China since the 2nd. Robert’s machine presented a crucial new chapter in the (at that point) 16-century-long history of paper; his paper machine was, in the overheated but not untrue words of paper’s towering historian, Dard Hunter, ‘destined to revolutionize civilization’, and enabled, among its many other consequences, the rise of the newspaper in the nineteenth and twentieth-centuries, and with it, a whole new relationship to information. But Robert died a long way from acclaim or success or even recognition. Given the significance of his invention, the monument that stands in front of the church in Vernouillet, erected in 1912, seems to mark not memory but eclipse.

A similar kind of injustice – a sense of both unrewarded ingenuity, and a fading from the historical record – defined the closing years of several others associated with the early years of the paper-making machine. This was a technology that seemed to disown its origins. Saint-Léger Didot (1767-1829) supported Robert’s early experiments but lost his paper-mill and his business and died broke; John Gamble was a pivotal figure in exporting the technology to England, where it first flourished, but his effacement from the history is such that it’s not even clear when, exactly, he died. Even Henry Fourdrinier, with his brother Sealy the head of the Fourdrinier firm for whom history at least has some memory, became bankrupt despite the success of the machine with his name, and survived until the age of 88, ‘in humble but cheerful retirement’ in a Staffordshire village on handouts raised by a testimonial organized by The Times.

In part these bathetic ends to talented lives are a reflection of the Wild-West-like instability of patent law at this time: early inventors struggled to hold on to ideas, and copy-cat models sprang up. It’s also a story of debtors who defaulted on promised payments, draining the inventor until they couldn’t go on: like Emperor Alexander I of Russia, who you’d think might have the cash, but who handed over nothing of the ten annual payments of £700 promised to Fourdrinier after the 1814 installation of two machines at Peterhof. But there is also a larger truth about the ways in which a great invention necessarily exceeds, and therefore betrays, the life of any single originator.

Robert turned over this fact – probably, surely – as he took his daily early evening walks round the sun-dappled square of Vernouillet.

***

There were writing surfaces before paper: baked clay tablets with wedge-shaped cuneiform marks from ca. 3,000 BCE Uruk, in present-day Iraq; papyrus reeds gathered from the banks of the Nile, peeled and layered to produce sheets, combined into scrolls; wax tablets, pairs bound to produce a diptych, or several bound to produce a codex (the Latin for ‘block of wood’, or ‘tree trunk’, and meaning later a block split into leaves or tablets for writing); parchment and vellum, made from animal skins, de-greased, de-haired, stretched and scraped, but often with veins and hairs still visible. Chinese writings were found by the Yellow River in a flood in 1899: 3,000 pieces in all, from about 1,300 BCE, inscribed on tortoise shells and animal bones. The urge to write – to make a mark, to signal presence, to transmit and store information – is registered in this variety of substrates, a variety which suggests both technological innovation and the need to use whatever is to hand.

Paper – which means, in words unlovely but true, ‘thin, felted material formed on flat, porous moulds from macerated vegetable fibre’ – may have been developed in China in the year 105 CE. Pass me that sheet of macerated vegetable fibre! It was almost certainly not an invention from nowhere but a modification of what Lothar Müller calls the ‘proto- paper’ already in use. The inventor may well have been Ts’ai (or Cai) Lun, a court official in charge of weapons for the Eastern Han dynasty. (Historians like to repeat the fact that he was a eunuch, although it’s not clear why this is important.) The process Ts’ai Lun introduced went something like this. The inner bark of the mulberry tree was soaked in water with wood ash and then processed, or mashed up, until the fibers separated. The watery fibers were poured onto a screen – cotton or hemp fabric stretched on a wooden frame – resting in water, and were spread out by hand. The screen was lifted and left to dry with the fibers on it: when dried, a sheet of paper was pulled off. It was a slow process – a papermaker might produce a few dozen sheets a day – but also, across centuries to come, a process that was remarkably constant.

From Asia, the technology spread to the Arab world, perhaps via a battle in 751 CE on the banks of the Tharaz River near Samarkand, in modern-day Uzbekistan, where Arab soldiers captured Chinese papermakers and with them secured paper knowledge. The romance of the story suggests a tidy myth serving to scoop up a more gradual process of dispersal across a series of military conflicts, and along the trade route of the Silk Road. But it’s certain that paper spread quickly across the Islamic world. It also developed as a technology, as Arab makers, needing to find resources abundant in their own lands, moved away from natural mulberry and began to use man-made linen and hempen rags – so linking paper production to cities, to areas of denser population, and to textile production. Paper mills of unprecedented scale and sophistication appeared in Baghdad in 793-4. Government bureaucrats began to use paper in place of papyrus and parchment and the Stationers’ Market (Suq al-warraqin) thronged with shops selling books and paper. The great writing culture of Islam between the 7th and 13th centuries, in which dazzlingly skilled calligraphers in Medina and elsewhere produced paper Korans, was fed by this later paper production. Paper mills followed in Damascus (soon famous for its delicate, light ‘bird paper’ – waraq al- tayr), Tripoli, Sicily, and through Tunisia and Egypt. In the 10th century, floating ship-mills, powered by the current, moored on the Tigris above Baghdad. By the 11th century, mills were producing paper in Fez: the delayed take-up perhaps due to the sustained dominance of parchment in a herding society.

When knowledge of papermaking arrived in Spain in about the 11th century via North Africa, paper was a medium, and paper-making a set of skills, definitively shaped by earlier Arab and, before it, Chinese, cultures. Perhaps because of this belatedness, European attitudes to paper-making were initially characterized by an arrogance built on deep foundations of ignorance. Europeans initially distrusted paper as a medium introduced by Jews and Arabs: in his Against the Inveterate Obduracy of the Jews, Peter the Venerable, Abbott of Cluny (ca. 1092-1156) condemned rag paper – ‘made from the scrapings of old cloths or perhaps even some more vile material’ – through an explicit association with Judaism. By the time Europeans had understood paper’s revolutionary potential, they set about systematically forgetting its Arabic, Chinese past, appropriating paper as its own, and refashioning its history into a story of European ingenuity. This was in part because of a booming early modern European paper-making industry that began to export to North Africa and West Asia: by the 18th century, when Europeans started to write paper’s history, papermaking had diminished massively across the Islamic world. For hundreds of years, Europeans had no sense that paper-making began in China ten centuries – ten centuries! – before it reached Spain. When in the seventeenth-century, Europeans witnessed paper-making in Japan and China, they assumed the origin of this Asian craft was Europe; Diderot and d’Alembert’s Encyclopédie (1765), that central text of the French Enlightenment that provided ‘a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts’, knew nothing of an Arabic past. If Europeans had really been interested in origins, they would have understood how the Chinese used a wide variety of grass and bark fibers, and so would surely have arrived at the idea of wood pulp as an alternative source to rags less belatedly than the 1840s.

By the thirteenth century, paper mills were booming in northern Italy: the mountainous town of Fabriano was the site of numerous paper-making innovations that drew on the town’s rich tradition of weaving and of metalwork (a blacksmith is il fabbro). Water-powered rag stampers hammered the macerated rags with a new efficiency; animal glue (boiled down deers’ feet and sheeps’ hoves: the stench was overwhelming) was used as sizing to stop ink from seeping through the paper and so to enable writing; and stiffer moulds were made from fine wire rather than bamboo or reeds. Medieval Fabriano was also the site of the invention of the watermark: a piece of wire attached to the mould producing the makers’ initials, or an image of a crown or a pot or a fool’s cap, symbols that linger today in the language of paper size. Around this time Europeans began to wear more linen than wool: supplies for rag paper increased, therefore, and paper mills were established in Nuremberg (1390), Ravensburg (1393), and Strasbourg (1445). In England – which at this point was late to just about every party – William Caxton, who, as we’ve seen, learnt to print in Cologne, had to import paper from the Lowlands because England had no papermaker until John Tate established the Sele Mill in Hertfordshire in the 1490s. The earliest extant paper from Tate’s mill survives in the form of a single-sheet papal Bull from 1494. Throughout much of the sixteenth and seventeenth century, British mills produced little white paper, and mostly made coarse, brown papers for wrapping; it took the arrival of skilled Huguenot paper makers, fleeing France after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes (1685), to bring a surge of manufacturing skill capable of producing fine white paper.

Thus the history of paper is a sprawling, complicated story ranging across thousands of miles and thousands of years – but it is also a story of relative constancy, of the possibility of recognition across time. By the 8th century there were paper mills operating in Japan producing paper with no yellowing acid content: a sheet looks the same today as 1,200years ago. The paper used by Gutenberg in the first printed Bible (1450-55), with its brilliantly clear bunch-of-grapes watermark, is of a time-defying quality unsurpassed by modern industrial processes …