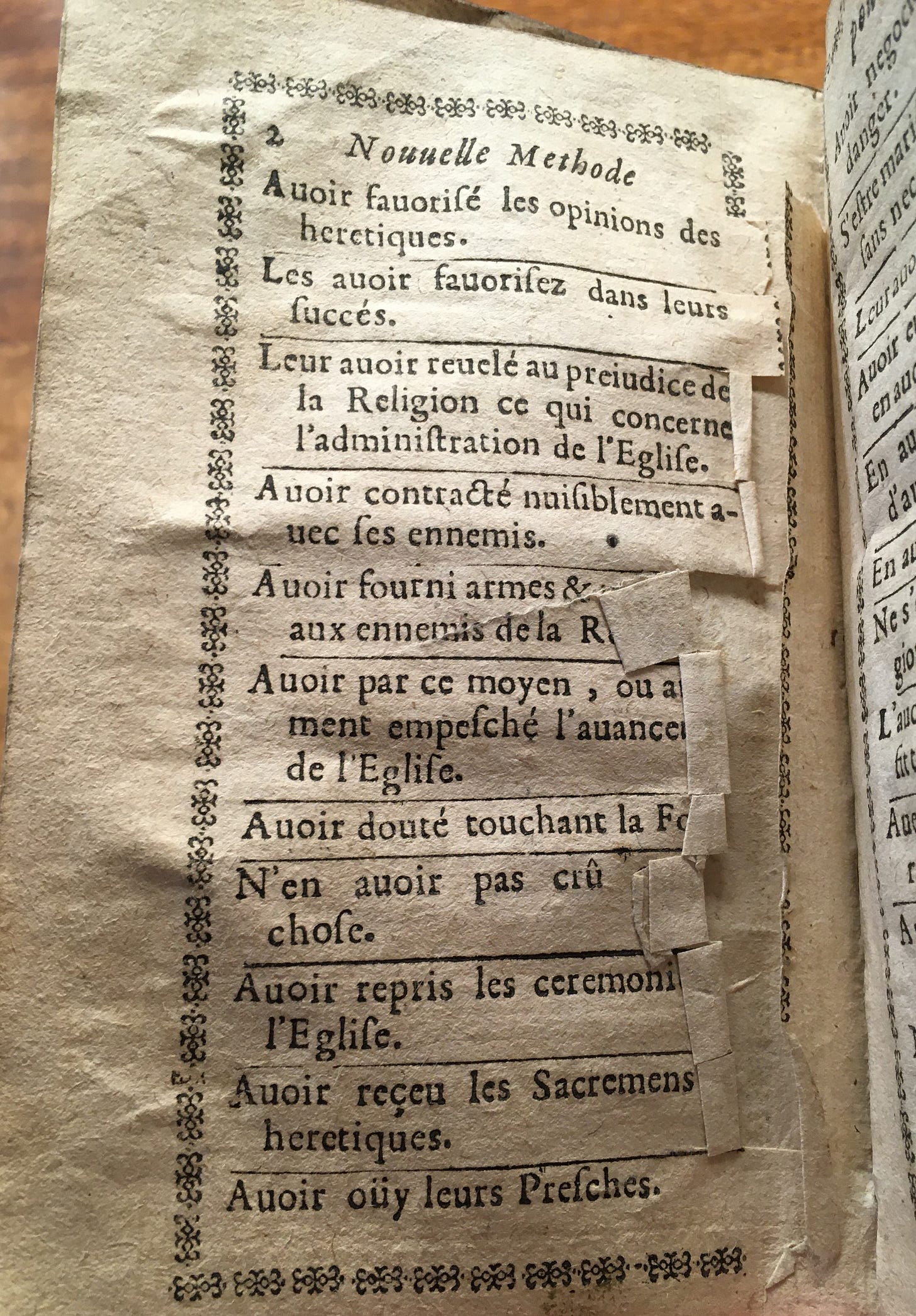

If you are having trouble remembering your sins in seventeenth-century France – if you feel you need some kind of spiritual prompt – then you could do worse than turn to Christophe Leutbrewer’s Nouuelle methode pour se disposer aisément à vne bonne & entiere confession de plusieurs années (1658). This is a Catholic confession book, or a confession coupée, featuring pages and pages of sins. Here’s one page listing transgressions to do with being impatient (‘Avoir esté trop impatient’), or delaying doing good deeds (‘Avoir differé de bien faire’), or – this does sound bad – persisting in sin (‘s'estre obstine dans le peche’).

The ‘Nouuelle’ in Leutbrewer’s Nouuelle methode was not the various kinds of human fallibility, but the page itself. Each of the sins was printed on a horizontal slice, separated from its neighbours above and below (but joined to the gutter). With a stylus or needle, the reader could unpick the particular sin from the margin and fold it back to serve as a reminder. Here, below, are some sins from the devotional life of an owner of the copy now in the Bodleian Library (Vet E3 f.506) – frozen in time at the last reading, like a kind of spiritual version of those Vesuvius victims found at Pompeii.

The brilliance of the design meant that after confession, the user could return each strip to its original, unfolded, unfallen, position, ready for the next cycle of sin / book-marking / confession. The page tracked the spiritual condition of the reader. Leutbrewer’s Nouuelle methode was a bestseller, and similar books were soon published in the Low Countries and in Mexico – versions like El pecador arrepentido. O methodo facil para disponerse a una buena Confession General, o particular (Mexico, 1716).

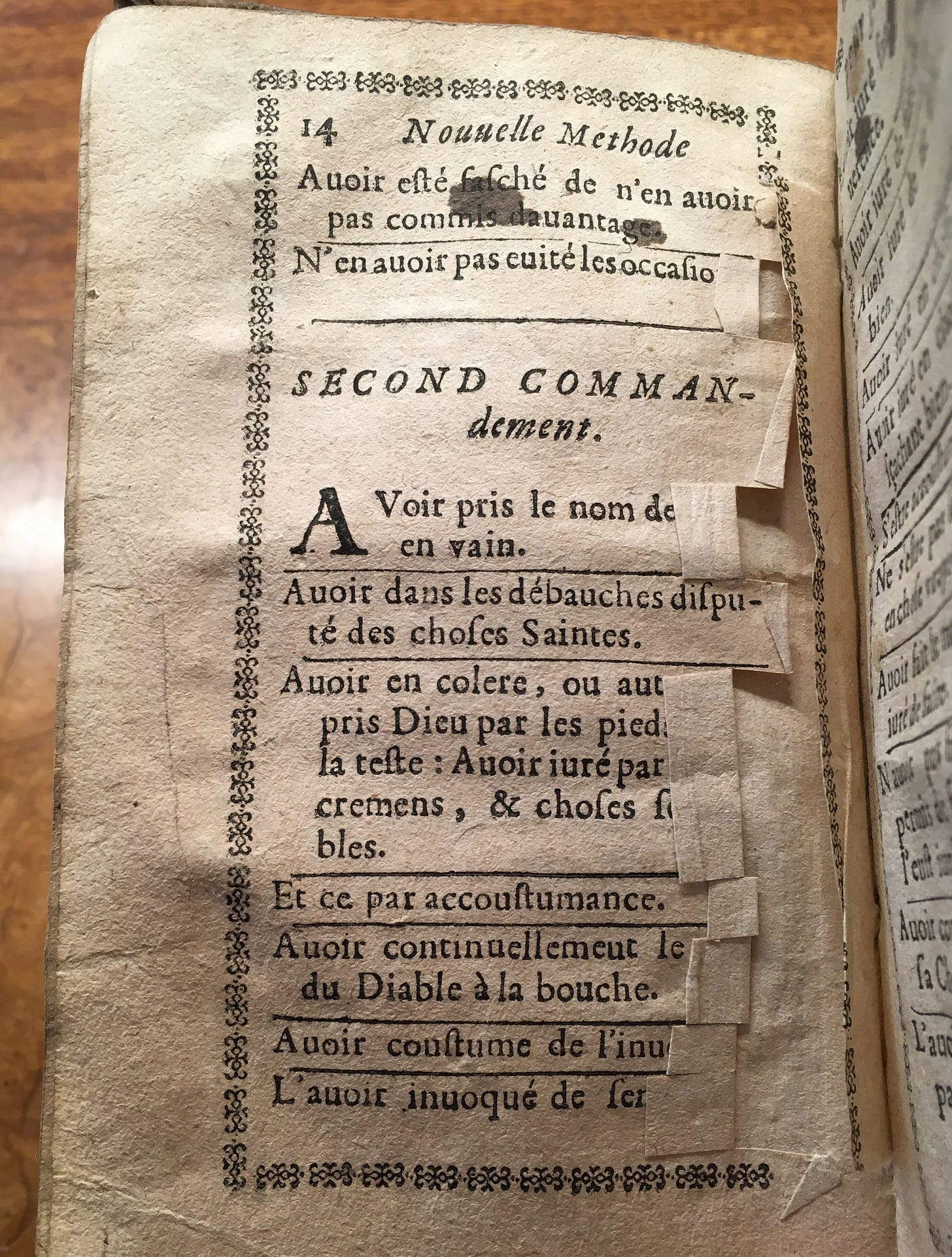

Here’s one more page from the Bodleian copy, this one with a busy cluster of action around the second commandment.

These books are interesting for so many reasons. As a script of sins they represent an instance of print culture very directly shaping religious subjectivity: to be a Christian, here, means locating one’s self in relation to this litany of prior printed mistakes. Where are you, amid this list? Who are you? It’s also a crucial moment in the history of the page as a unit: a moment when something whole is sliced into strips that move and return, when the page becomes permutational, following us, but also shaping us.

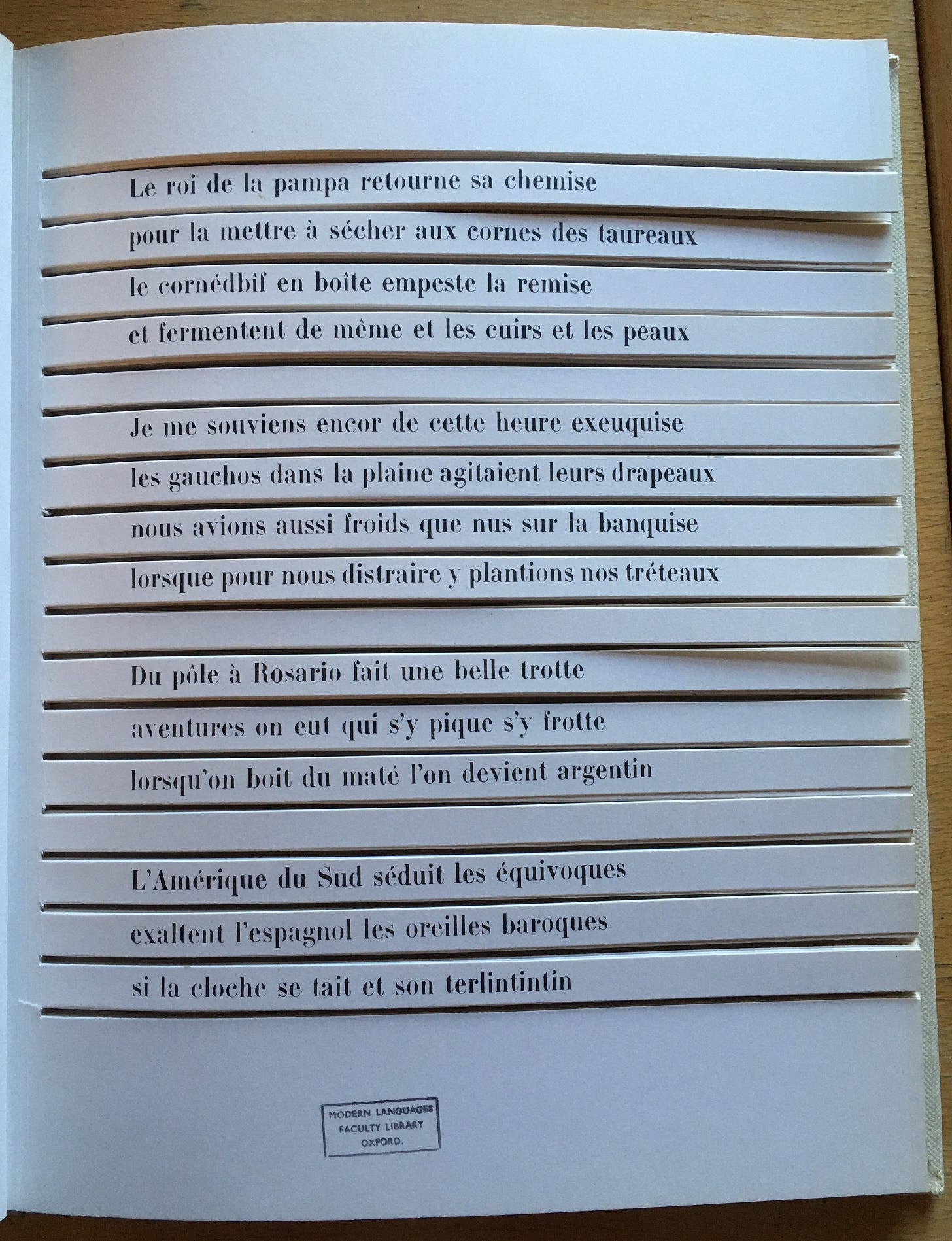

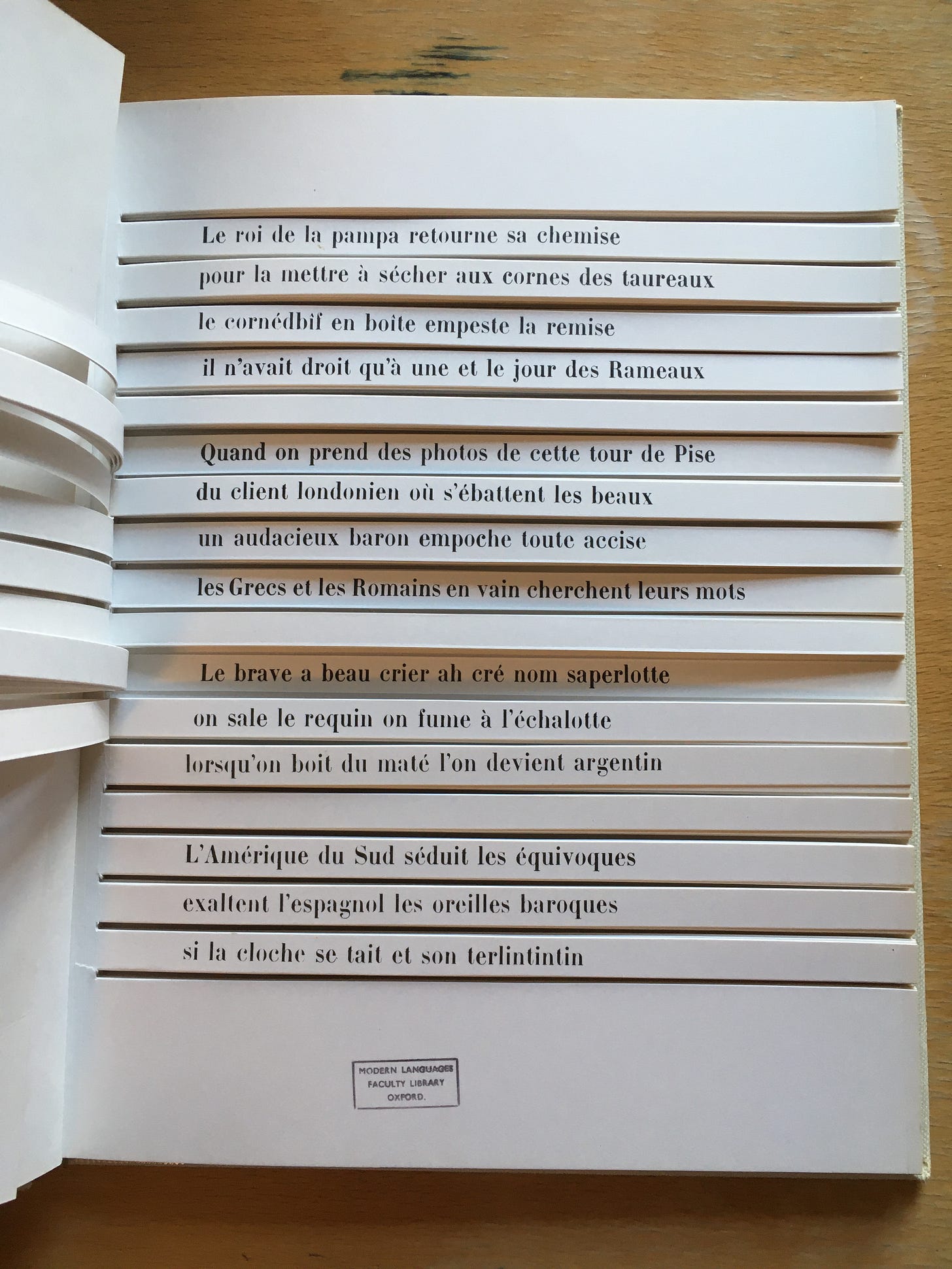

I don’t know if the French novelist and poet Raymond Queneau (1903-1976) knew anything about the confession coupée, but he achieved a similar relationship with the page in his Cent mille milliards de poèmes (A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems), published in 1961. Here is the page that you’re faced with if you open the Gallimard edition from that year.

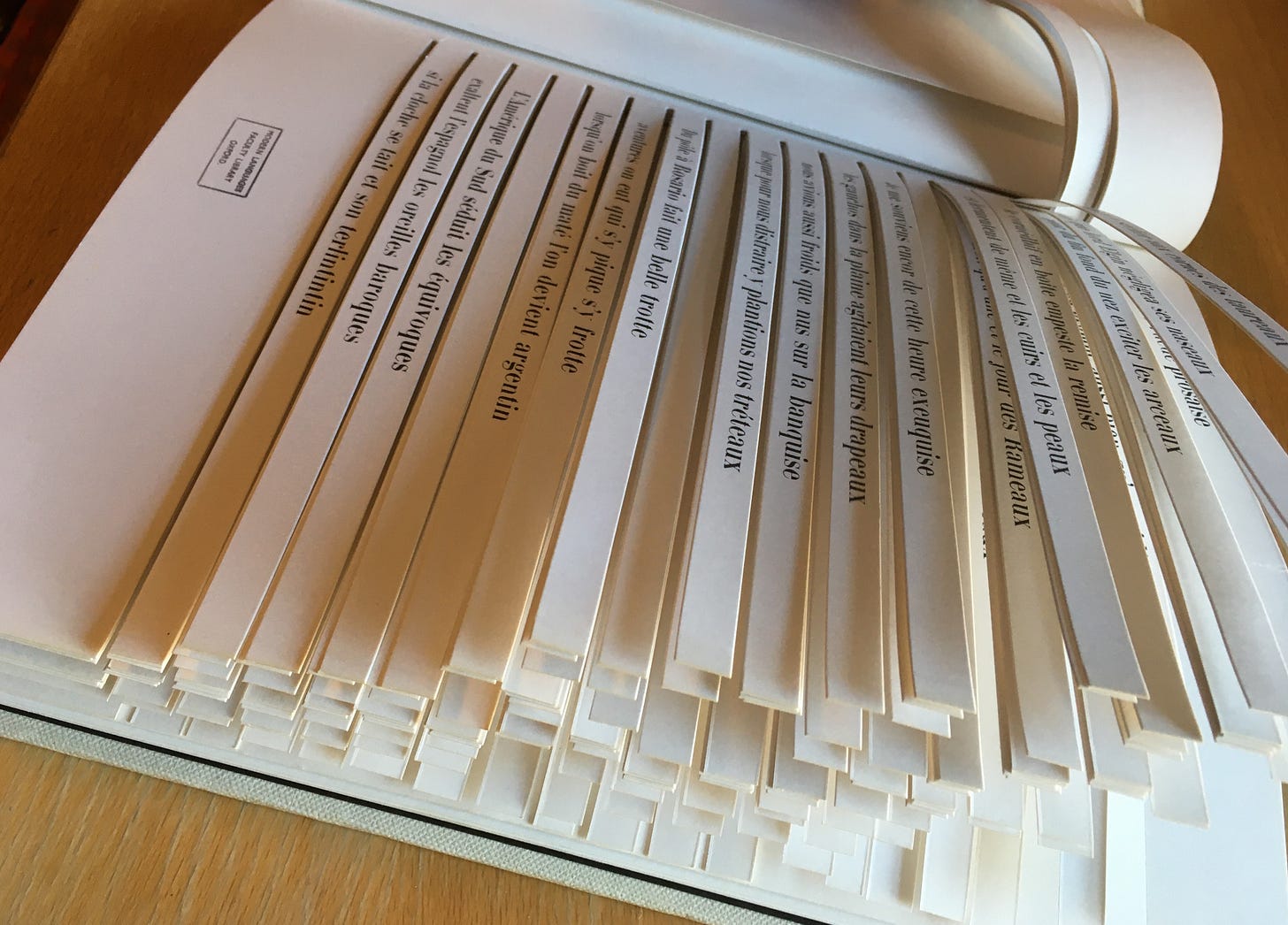

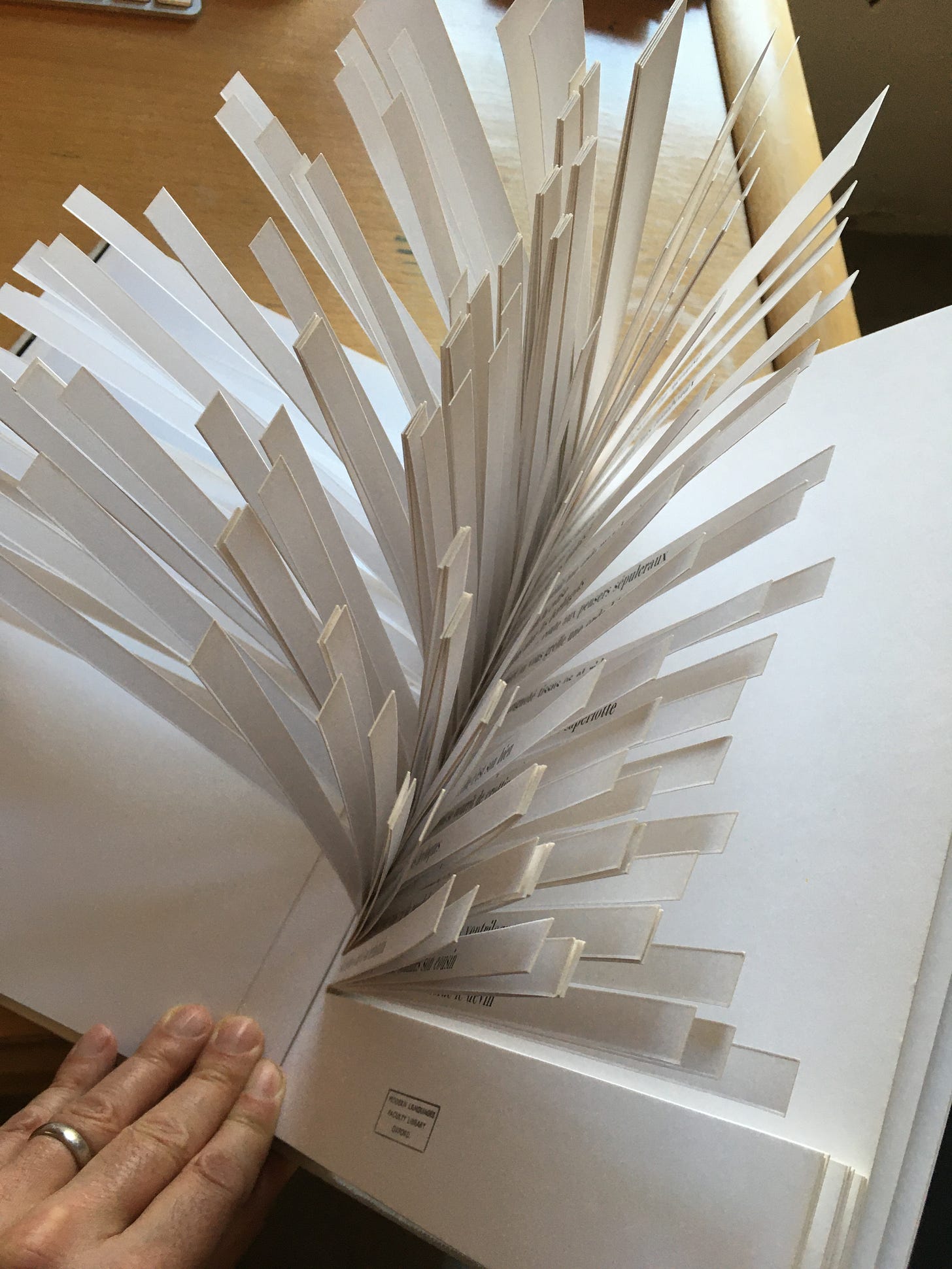

This is a sonnet, with each line on a horizonal slip, like Leutbrewer’s Nouuelle methode. But each line is 10 strips deep, and there are 14 lines, meaning that the slips can (in theory) be rearranged to produce 10 to the power of 14 different sonnets. You can get a sense of this depth – of the lines beneath each line – here:

And of the strange pluming thing the page has become, here:

Where Leutbrewer’s text was, we might say, a disciplinary technology, Queneau’s page is a machine for producing an almost infinite number of poems.

10 to the power of 14 sonnets means 100,000,000,000,000 sonnets, which Queneau estimated would take 200 million years to read. Which is more than enough sonnets!

A good job the novelty 18 line sonnet championed by Thomas Watson in 'Hekatompathia', never caught on. https://blogs.bl.uk/english-and-drama/2016/08/visual-verses-thomas-watsons-hekatompathia-or-passionate-century-of-love-1582.