One of the features of books is their tendency to describe their own history: as the bibliographer and literary critic D.F. McKenzie wrote, ‘every book tells a story quite apart from that recounted by its text’.

Henry Dugdale Sykes’s Sidelights on Shakespeare (1919) is a set of essays on the authorship of Two Noble Kinsmen, Henry VIII, Arden of Faversham, A Yorkshire Tragedy, King John, King Leir, and Pericles. T.S. Eliot called Sykes ‘perhaps our greatest authority on the texts of Tourneur and Middleton’, which sounds like the perfect back-handed compliment, and indeed as editor of The Criterion, Eliot penned a deft rejection letter to Sykes in 1923 (‘I am afraid your paper [on Middleton] is too technical to give me the right to include it to the exclusion of certain other things. It is with great regret that I release it to you’).

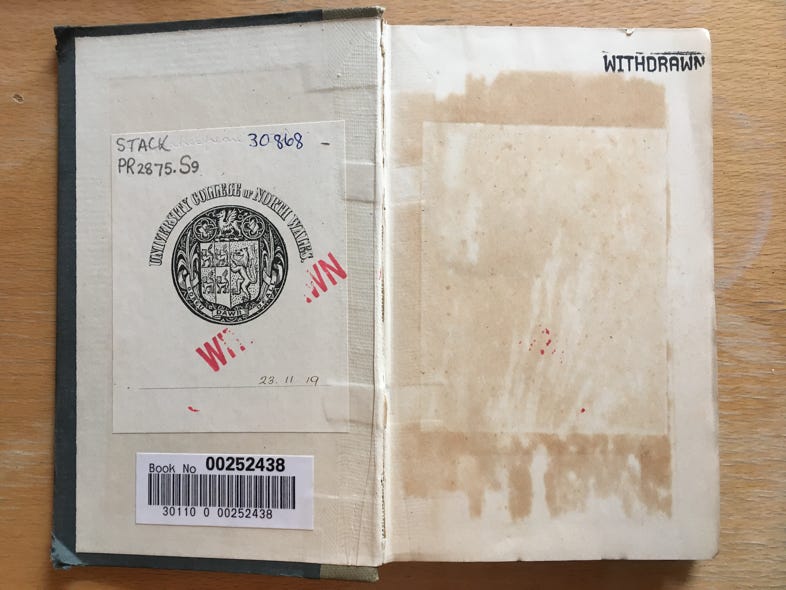

My copy of Sidelights on Shakespeare shows a life of movement and stasis (but mainly stasis), of selection and then rejection, revealed in the marks and wounds we see when we open the volume. Published by the Shakespeare Head Press in Stratford-upon-Avon in 1919, a year and a month after the armistice, Sykes’s book arrived at University College of North Wales (founded in 1884, and now Bangor University) on 23 November 1919, sat on the shelves in at least two different positions, was tagged by hand and then later by bar code, and was then withdrawn from circulation.

The book also carries evidence of its journeys, like stamps in a passport, on the title-page -

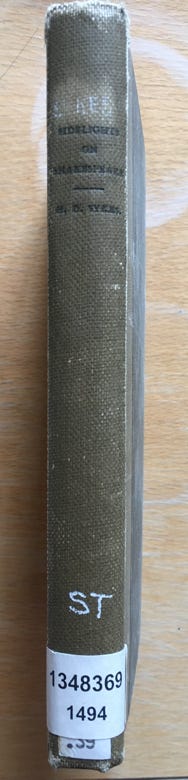

- and on the spine, with one shelfmark bandaged over another.

These are the most everyday tags on a book, but at the same time: there is so much to see here!

A second example of books telling their material history, from a long time ago. Wynkyn de Worde may have the best name in printing history (disappointingly, his nickname seems to have been ‘John’). ‘De Worde’ suggests a birthplace, which might be Woerden in Holland, although – you can imagine – historians have been debating this for more than a century. De Wordean books have a particular tendency to self-narrate: to describe, self-reflexively, their own origins. Here is the colophon to his Nychodemus Gospell (1509), a book commissioned, like several he printed, by Lady Margaret Beaufort (1443-1509), Countess of Richmond and Derby, and mother of King Henry VII. The colophon is so punctually dated that we can imagine de Worde inspecting the wet sheets hanging from strings in his Fleet Street print shop, and de Worde styles himself ‘prynter unto the moost excellent pryncesse my lady the kynges moder [mother]’:

We get a fuller version of the same tendency in De proprietatibus rerum (1495), a vast reference guide to the properties of things. De Worde’s was the first printed edition of the English translation of this influential 13th-century work of science that had been a huge hit in manuscript. In the epilogue we are offered a vignette of the book’s making.

And also of your charyte call to remembraunce

The soule of William Caxton, first prynter of this boke

In Laten tonge at Coleyn [Cologne] hysself to avaunce,

That every well-disposed man may theron loke:

And John Tate the younger joye mote [may] he broke,

Which late hathe in Englond doo make this paper thynne,

That now in our Englysshe this boke is printed inne.

The book remembers the soul of the departed Caxton (de Worde’s former master), who printed a Latin version in Cologne, and records also that this is a book printed on paper made in England by John Tate the Younger. Tate was a former merchant dealing in fine cloth who converted a water-powered mill upstream from Hertford into England’s first paper mill, the exception to English reliance on paper imported from Italy and France, which ran from about 1480 for some 20 years. De Worde’s book is one of the very first printed on paper made in England. We know this because the book tells us: here I am, it says; this – future readers – is where I come from. Hold the pages up to the light and you can still see Tate’s watermark, an elegant 8-pointed star or petal set in a double circle.

Ah, the colophon. Thanks for those De Wordean examples. I enjoyed them almost as much as the colophons in the middle(!) of Inscription, Issues 1&2. Here are some other examples for fun: http://books-on-books.com/2019/04/23/the-colophon-and-the-left-over-i/

Enjoyable as always, I'm looking forward to sharing your blog with colleagues of mine this summer during a rare book seminar. Many thanks