Scraps of paper

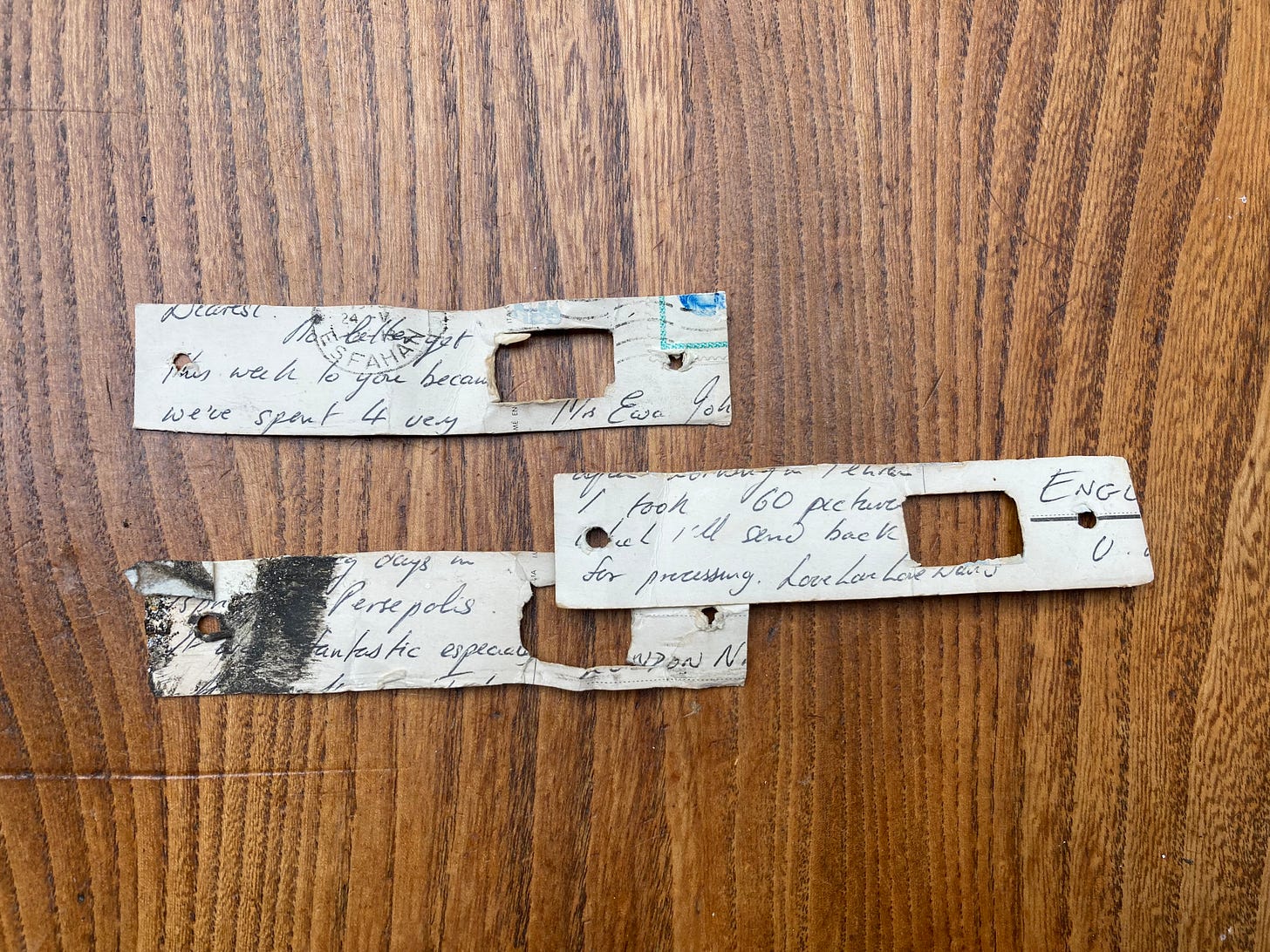

I had to take a lock off a door last week and underneath I found 3 layers of paper, serving as a support, cut from a postcard sent and received some time in the past.

Sliced to fit the shape of the lock, the strips reveal only pieces of an original image and text. On one side – architectural scenes I didn’t recognise. On the other: ‘Dearest’ – ‘we’ve spent 4 very’ – ‘I took 60 pictures’ – ‘send back for processing’ – ‘Love love love’ – ‘Persepolis’. The ruined palaces and grand entrances of Persepolis are in south-west Iran, close to modern day Shiraz – they were begun about 518 BCE by Darius the Great. So: a sight-seeing holiday. Hesitating between discarding the scraps and keeping them, I put them in a drawer and close it.

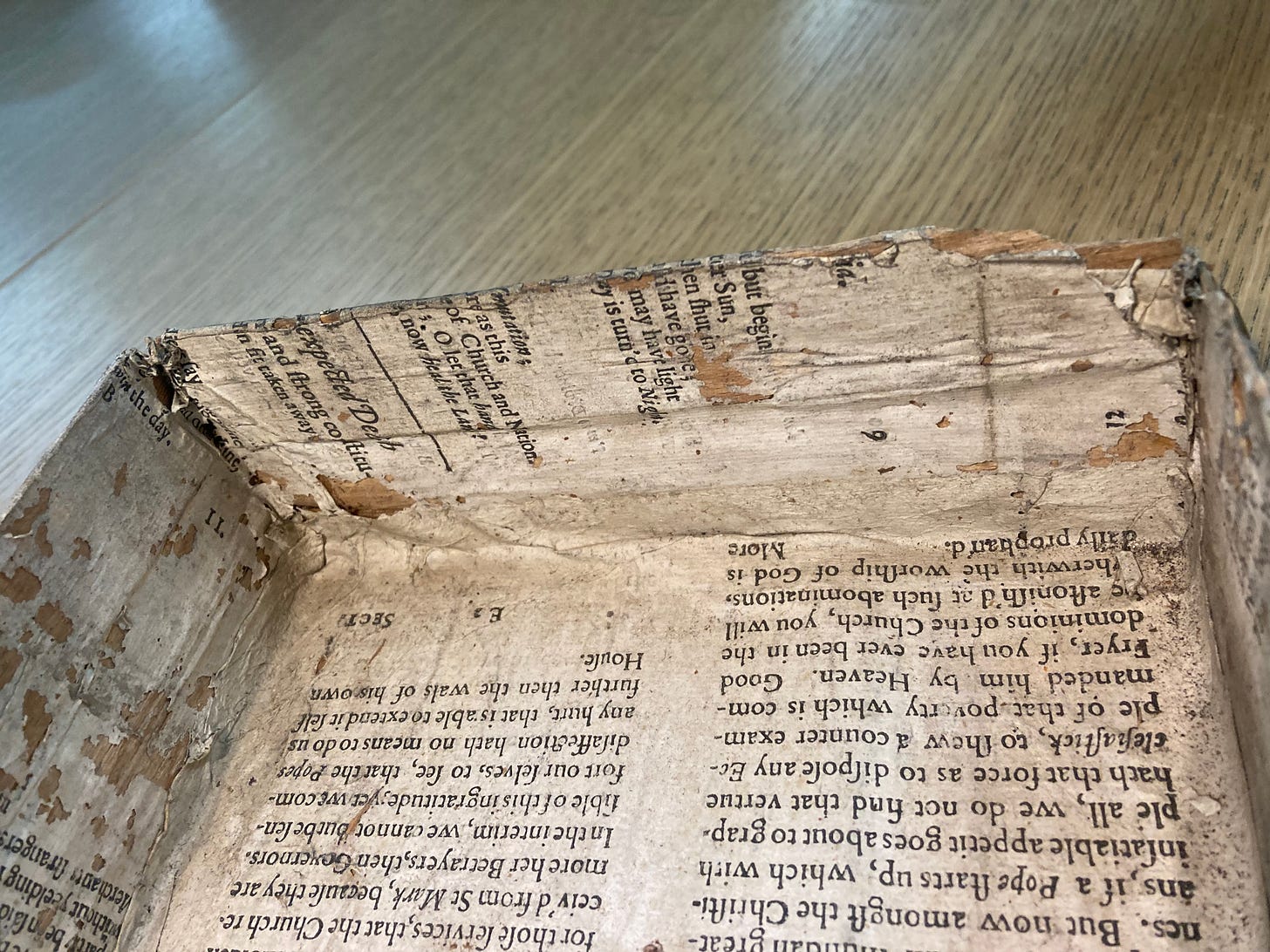

Last week at the National Archives in Kew, I was looking at a 17th-century box that has the unlovely name C 107/129. In fact it’s a deed box, full of handwritten 17th and 18th legal documents – wills and rental agreements. Take off the lid and you get this kind of thing bursting out at you:

Remove the vellum manuscripts and you can see the box itself. The lid, sides, and base have been lined with pages of print. After a little digging, we can work out that this box is covered with sheets that were once intended to be 3 different mid-17th-century pamphlets, but which never made it into their finished form.

From 1646: Justa honoraria: or, funeral rites in honor to the great memorial of my deceased master, the Right Honorable, Robert Earl of Essex. From 1644: St Paul’s late progres upon earth, about a divorce ’twixt Christ and the Church of Rome. And from 1641: The libertie of the subject: against the pretended power of impositions. Perhaps the sheets had errors, or perhaps too many were printed. Whatever the cause, they were no longer needed as texts to be sold and read, and were repurposed, before they could be folded and stitched, as a lining for this box. If we peer close, we can still read bits of the latent pamphlets. There are other copies of these pamphlets in libraries in the UK and North America, but sometimes this kind of re-use preserves otherwise entirely lost texts – their status as waste paradoxically ensuring their survival. These lined boxes suggest also how often in the past, as now, printed words came at readers not in the shape of the tidy codex, but in more plural, non-bookish forms: pasted on walls, or pinned to doors, or cast on the ground, or lining boxes.

String a twine through the holes and you get perfect bookmarks! To me it looks like the Khaju Bridge in Isfahan. What do you think?