Re-using woodblocks

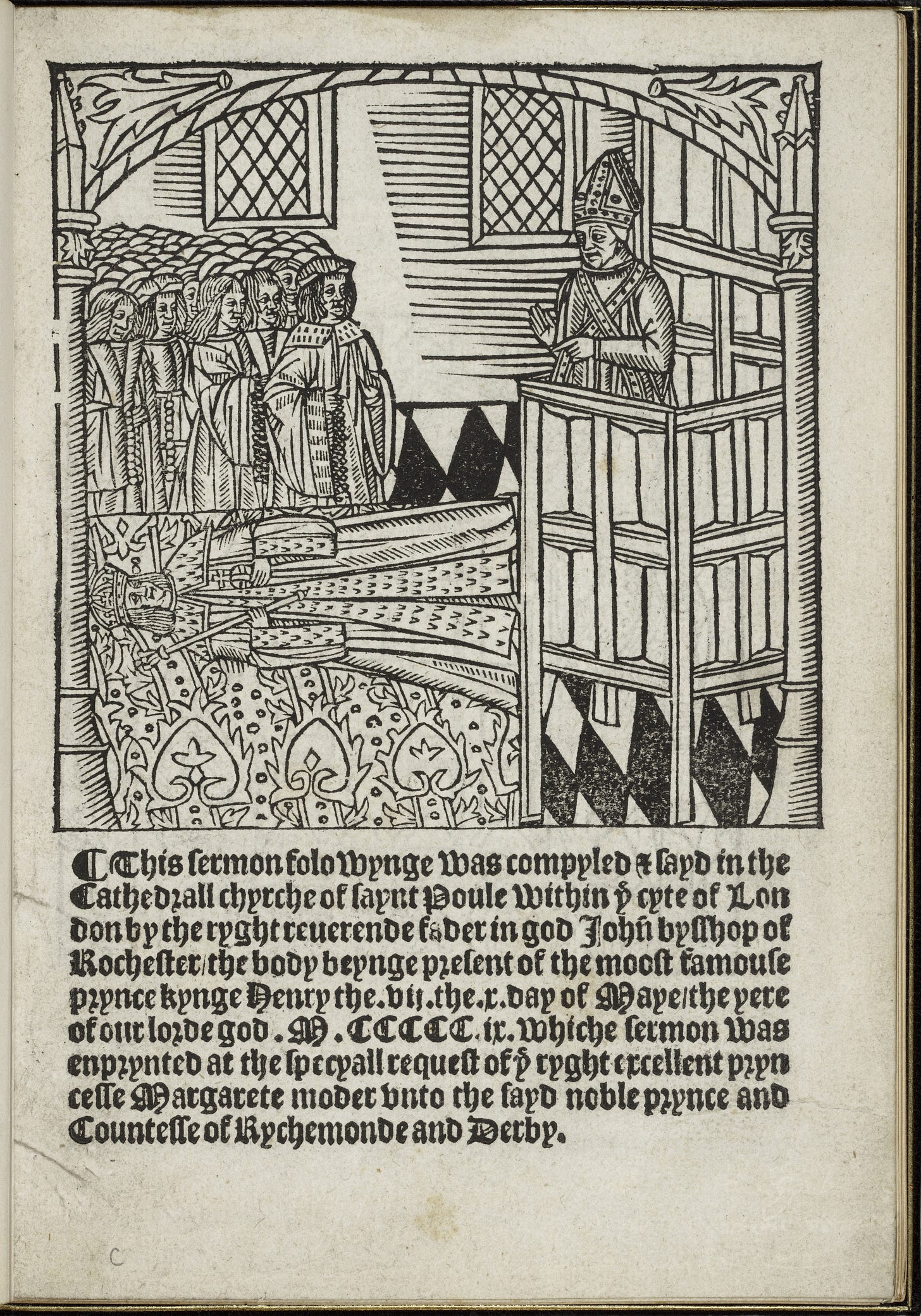

It’s quite often the case in early printed books that the same images reappear in different scenes, within books, and across different books. Woodblocks were expensive pieces of hardware, so better to reuse blocks already in-house than buy or commission new ones. That image of a courting couple, embracing outside on the ground, used in The Beggar’s Delight? Perfect also for The Hampshire Miller, Short and Thick. (These were ballads in the 1680s.) The great early London printer Wynkyn de Worde was an enthusiastic re-user across lots of his publications. In The Assembly of Gods (1500), a series of reprints of John Lydgate’s shorter poems, de Worde used a woodblock intended to represent the assembled gods that had been previously used to illustrate the very ungodlike pilgrims in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. And here below are two title-page examples. First up is de Worde’s edition of the sermon delivered at the funeral of Henry VII in 1509 by John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester. I love the dead king: a picture of a living Henry, flipped horizontal to denote death, as though he’s lying down, or has been run over, or is maybe wandering through a different plane of existence. Who cares about perspective when your king has died?

12 years later, de Worde came to reuse the same woodcut for a 1521 sermon by Fisher against ‘the pernicious doctrine of Martin Luther’. Pulpits are similar, as are mitres and crowds, and pretty much all de Worde did was cover the no-longer-relevant king with the opening blackletter text. A sort of second burial. The broken border on the left gives the game away, but probably only if you were a massive Bishop of Rochester fan and remembered the earlier title-page.

Today we might see these visual repetitions as dubious shortcuts: failures of book production for which de Worde deserves reprimand. But I don’t think that’s right. This kind of image-recycling was common in print across the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, particularly in broadsheet ballads. Readers would have expected these repetitions, and rather than feeling that something was amiss, may have drawn connections between the flashes of visual repetition. After all, this was a culture deeply familiar with the re-presentation of biblical and classical figures and narratives, and reiterated woodcuts no doubt prompted some readers to make links between the repetitions – in this instance, perhaps, between the death of a king, and a new doctrine blowing in from Germany.

A pedantic point: I think the king would probably have been cut out of the block, not covered up, else the type would not have sat level in the forme. A portion of his gown is still visible on the right.

Mike

It’s the ones that appear across publications by different printers that I find most intriguing. One cause is presumably stock being sold or passed on when someone dies or goes out of business. But in the early 1640s for example you find the same woodcuts appearing in close succession in rival printers’ works. I like to imagine someone popping round the corner to borrow one from a colleague: “I really need a bishop and a ghost to illustrate this quarto satire about Laud… have you got anything?”. Or perhaps the carvers retained ownership of the block in some cases and flogged them to various printers? I don’t have a sense of whether carving the woodblocks was a specialised trade in its own right or just something given to apprentices who had shown a knack for it.