If you are a bibliophile in London in the second half of the nineteenth century – or if you are any kind of reader at all – it’s likely you spend a good chunk of time at Mudie’s Select Library, where New Oxford Street meets Museum Street, near the British Museum. The annual subscription of one guinea (about £60 in 2022) undercuts Mudie’s rivals, and Mudie’s stocks are vast. In 1855, Mudie buys 2,500 copies of volumes 3 and 4 of Macaulay’s History of England. That’s eight tons of Thomas Macaulay. That’s Macaulay for everyone! An atmosphere of whispered efficiency fills the halls: the lifts, the iron staircases, the attendants communicating via speaking tubes. Light carts circulate from room to room, ‘laden with books’, and (in the words of London society) ‘the carriages block up Museum Street and New Oxford Street’ as ‘powder-headed footmen carry to and fro the packages of books.’ The impression is of a purring library machine that will run forever.

60 years later, in the 1920s, the library is still running with an atmosphere of frozen Victorianism. Wyndham Lewis describes Mudie’s as ‘solid as roast beef,’ and ‘about the only place in London where you could still find muttonchop whiskers, lorgnettes, tall hats from late-Victorian blocks, feathered and flowered toques.’ Here is the building in 1925.

The library is finally closed by a court order on 12 July 1937: The Times describes the event as ‘the extinction of … a national institution.’ By 1945, the building is pulled down, and the lot is advertised for sale next to posters for Guinness and ‘Senior’s fish and meat pastes’. (The camera’s long exposure means several of the pedestrians are reduced to spectral legs.)

In February 2022, the lot is filled with a building: anonymous-looking offices above, and with a ground floor that is available for rent for ‘restaurant use.’

If we visit and observe this plot of land, are these earlier periods in any sense present or alive? They are recorded in archives, and sustained in photographs, and we can recover them this way. But can this temporal depth be felt at the site? The shape of the new building seems to follow Mudie’s Library – at first it’s tempting to think they are the same shell, but it’s an entirely new construction. Presumably the location, and the shape of the lot, and the position of the roads, implies a certain building shape to architects in the mid-nineteenth century as much as today. But does this plot of land carry these past moments with it?

There are some riveting attempts to capture this sense of a single location existing at different moments, and these moments being simultaneously felt. ‘There rolls the deep where grew the tree’, writes Tennyson in ‘In Memoriam’, as he returns to the house where his beloved Arthur Hallam once lived:

He is not here; but far away

The noise of life begins again,

And ghastly thro' the drizzling rain

On the bald street breaks the blank day.

John Stow’s Survey of London (1598, 1603) is a work of chorography (place-writing), a kind of prose map of London, a walking (or ‘perambulation’) through the city, ward-by-ward, that, as it traverses space, also conveys the past beneath the streets: it moves horizontally and vertically at the same time. The Survey is deeply nostalgic for the lost customs and ceremonies and personalities Stow remembers from his childhood, and his work tries to keep these alive, even as he describes a London that is in the process of making itself anew. Near the end of his life, Stow (1525-1605) told George Buck (1560-1622) how he had talked with old men who remembered Richard III (1452-85) and ‘affirmed that he was not deformed, but of person and bodily shape comely enough.’

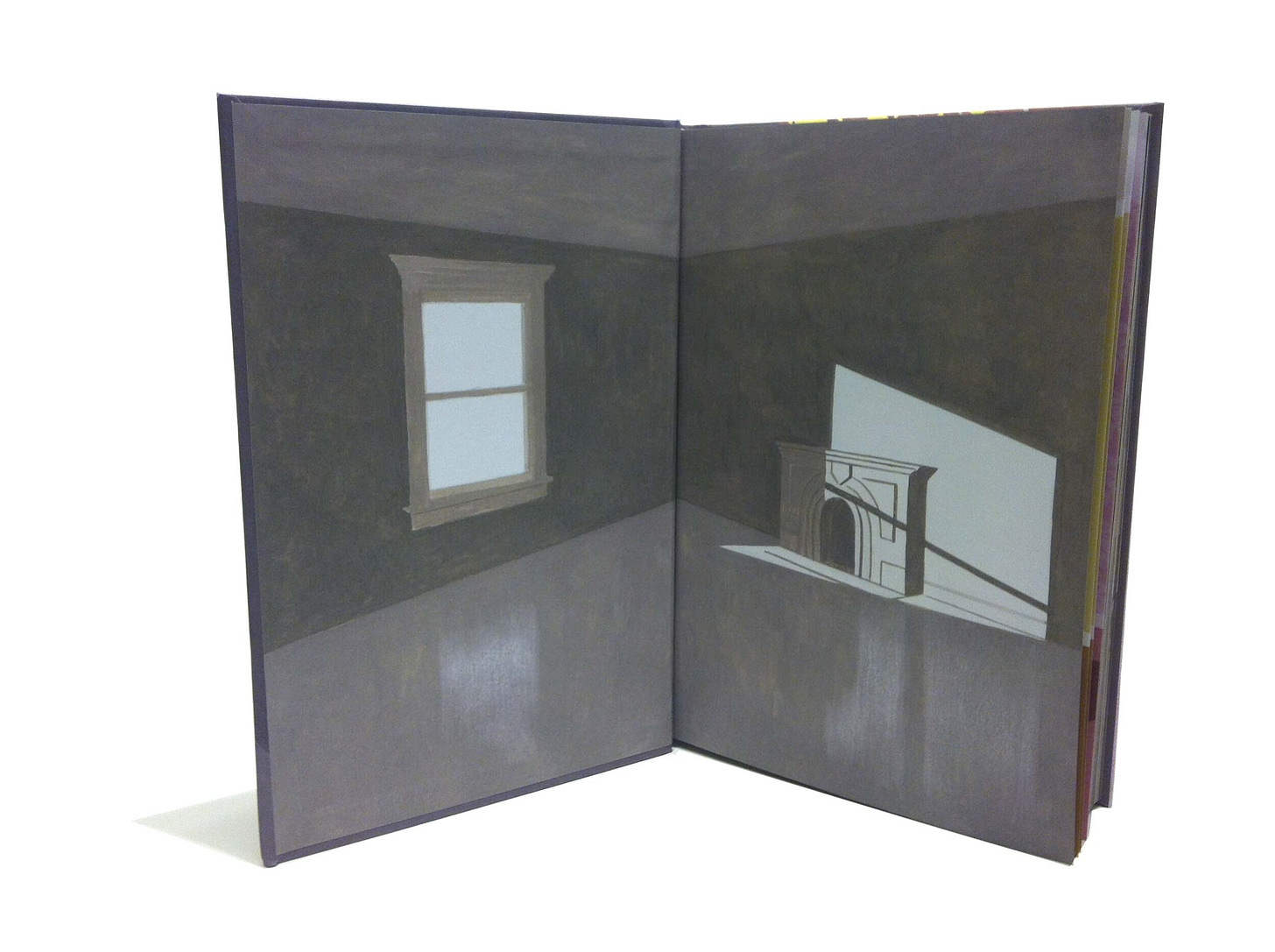

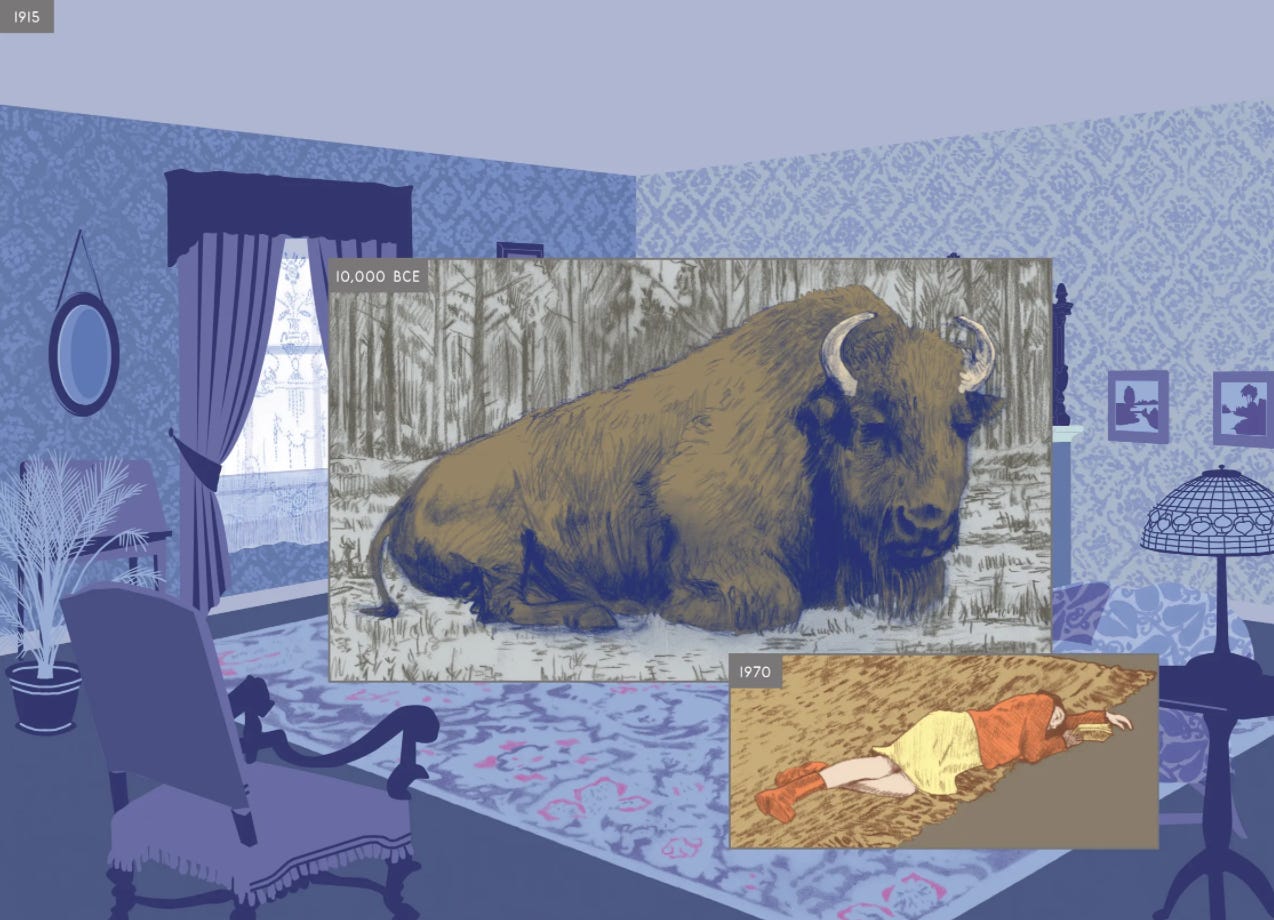

By far the most powerful exploration of this terrain I know is Richard McGuire’s Here (2014). McGuire calls this ‘an artist book disguised as a graphic novel about one location over time’. A corner of an unremarkable-looking room is tracked through time – we are flung between sudden, non-chronological moments (1915 to 2016 to 1933 to 1609 to 10,000 BCE). The full temporal range of the book covers 500,957,406,073 BCE to 2033 CE; the spatial coverage is about 30 square metres. Here is the start.

Soon we get multiple slices of time coming at us at once – the same space, in 2014 and 1503; then 1964, 1932, 2014, and 1993; then 1915, 10,000 BCE, and 1970.

What would the prose equivalent of this kind of temporal simultaneity be? In the spirit of Richard McGuire, here is the space where New Oxford Street meets Museum Street, in February 2022, but with slices of 1925 and 1945 within it.

It is worth noting that New Oxford Street is very much a cordon sanitaire, a 19th century extension of Oxford Street itself, and designed to separate the posh terraces and squares of Bloomsbury, from St Giles, on the south side of the road. This was known as one of the worst rookeries in all of London, an overcrowded quartier of ruinous tenements their broken windows patched with hessian, the gutters strewn with filth. It was home though to many Irish immigrants, especially from Cork, who arrived in London after the Great Famine (my great-grandfather among them), and proudly boasted a notorious pub called the Rat's Castle at its centre. Michael Faber's 2002 novel 'The Crimson Petal and the White' (another Tennyson reference incidentally) uses St Giles as a backdrop for its account of a young prostitute who manages to lift herself out of this squalor. So it is doubtful if Mudie's got much custom from this abject demographic!

"Here" is indeed a remarkable work of imagination, though I confess I find his choice of colours offputting. The interactions of time, space, and multi-generational memory are like ghosts, I think, more often felt than seen, and unpredictably intermittent. You can't seek them out -- "never go back" is excellent advice -- but they will take you by surprise.

It's a subject close to the heart of anyone of an age where practically every site of significance in your own life has been demolished, or transformed beyond recognition. I think something of the sort is what Bowie was aiming at in "Where Are We Now?": "a man lost in time near KaDeWe..." If I may, I'd like to point you at a post from my blog, exploring an attempt to recover one such chunk of lost time and space:

https://idiotic-hat.blogspot.com/2017/07/forty-seven-memory-palace.html

Mike