The many notebooks I’ve filled in recent years are normally scattered across various drawers and desks but last week I gathered them into a single pile and they look like this.

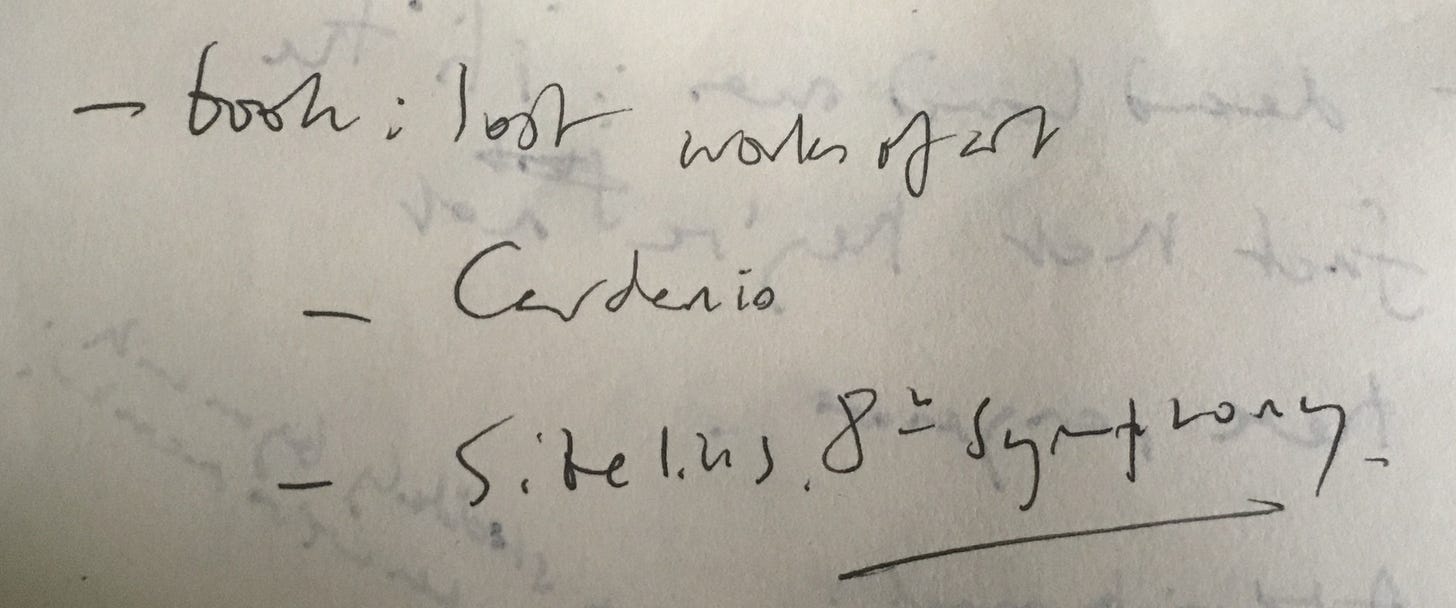

Lots of the notes are ideas for projects, or essays, or pieces of writing of various kinds, like

or

Neither of these notes ended up as the projects they promised. In fact, only a tiny minority of notes represent early stages of things that became bigger things, like this struck-through list of 17th-century commonplace books (left) that surfaced years later in a book on life-writing, and the long list of obscure alcoholic terms (right) which dates from around 2004 when I was editing a book called Drink and Conviviality in Seventeenth-Century England.

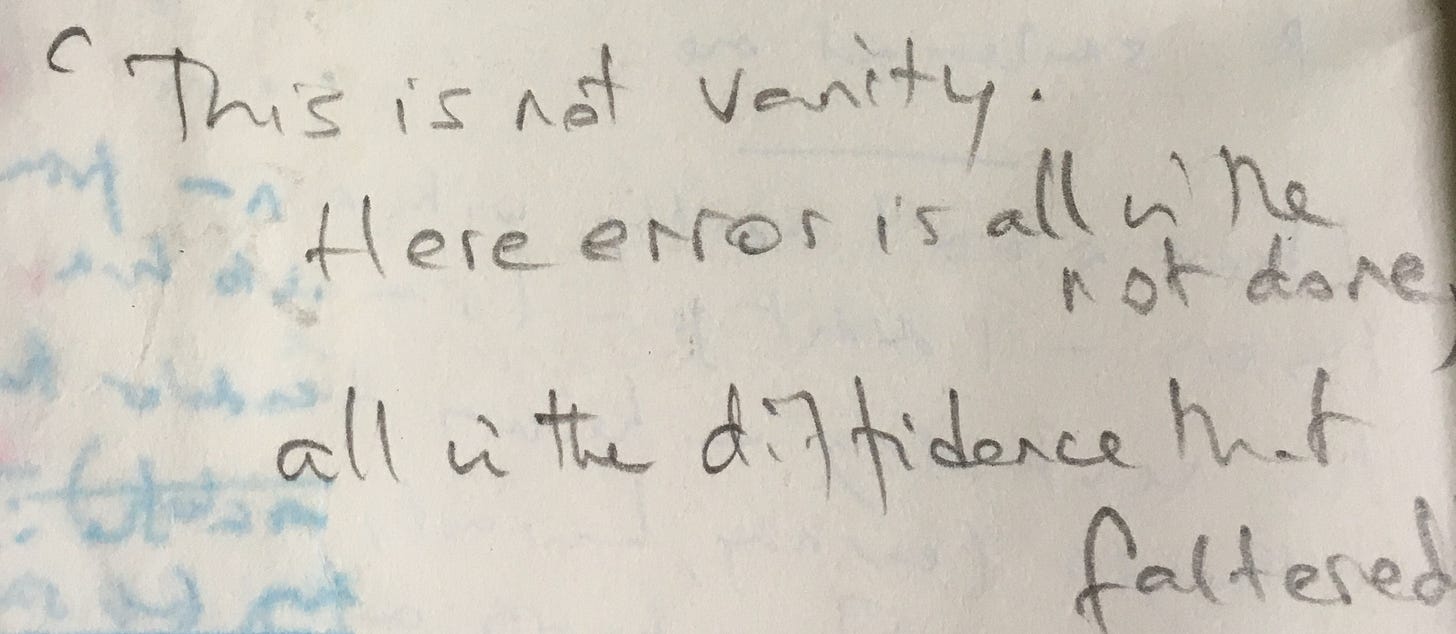

Most of the notes lack any sense of telos: they are decontextualised brevities that can’t possibly ‘make sense’ but which record something striking me at a moment in the past in ways I can usually not understand now, like

or

There are hundreds and hundreds of these. What was I thinking? There are also lots of lines excised from books I was reading which come at me now anew.

There are unattributed quotes, floating free.

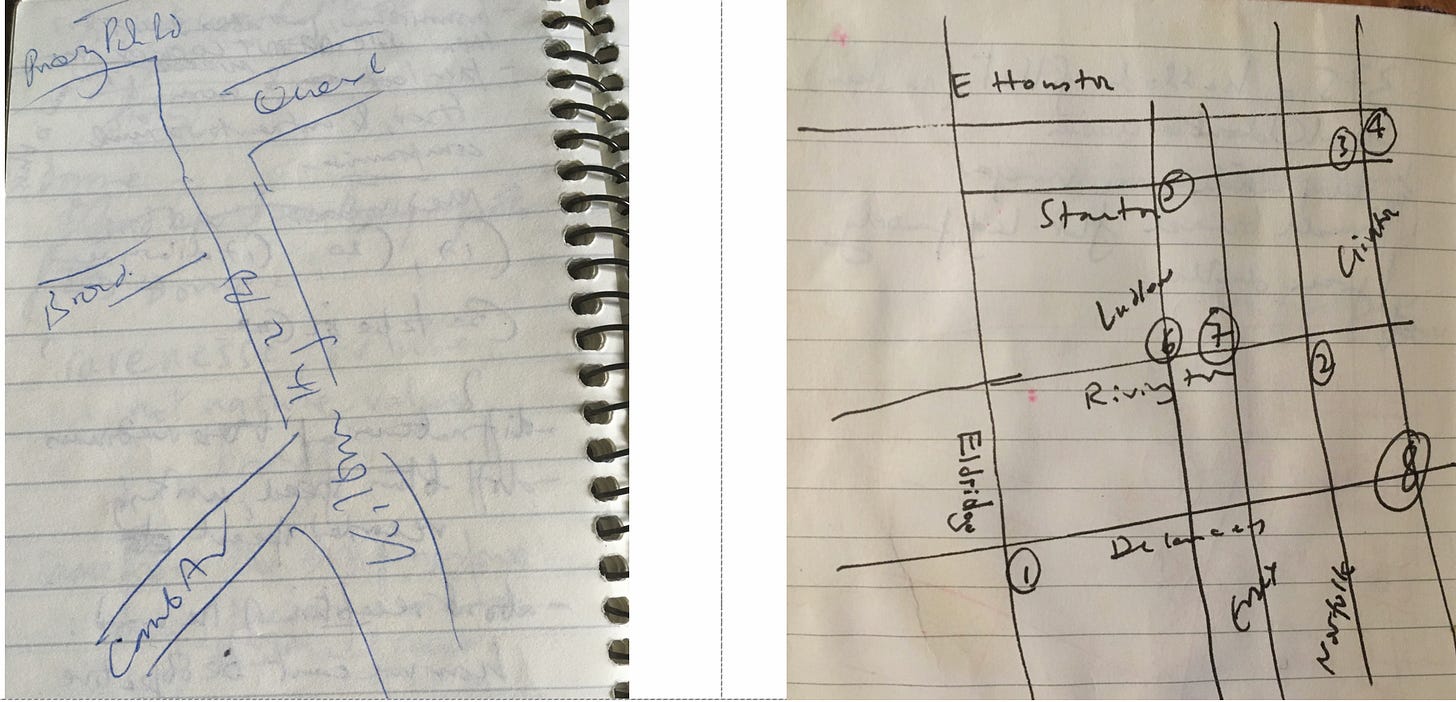

There are lots of recipes, and administrative bits and pieces (flat-hunting scraps from the 1990s when you could get a studio in Bloomsbury for £70 a week), and also a form that the smart phone has killed off, but which I like: the hastily sketched map.

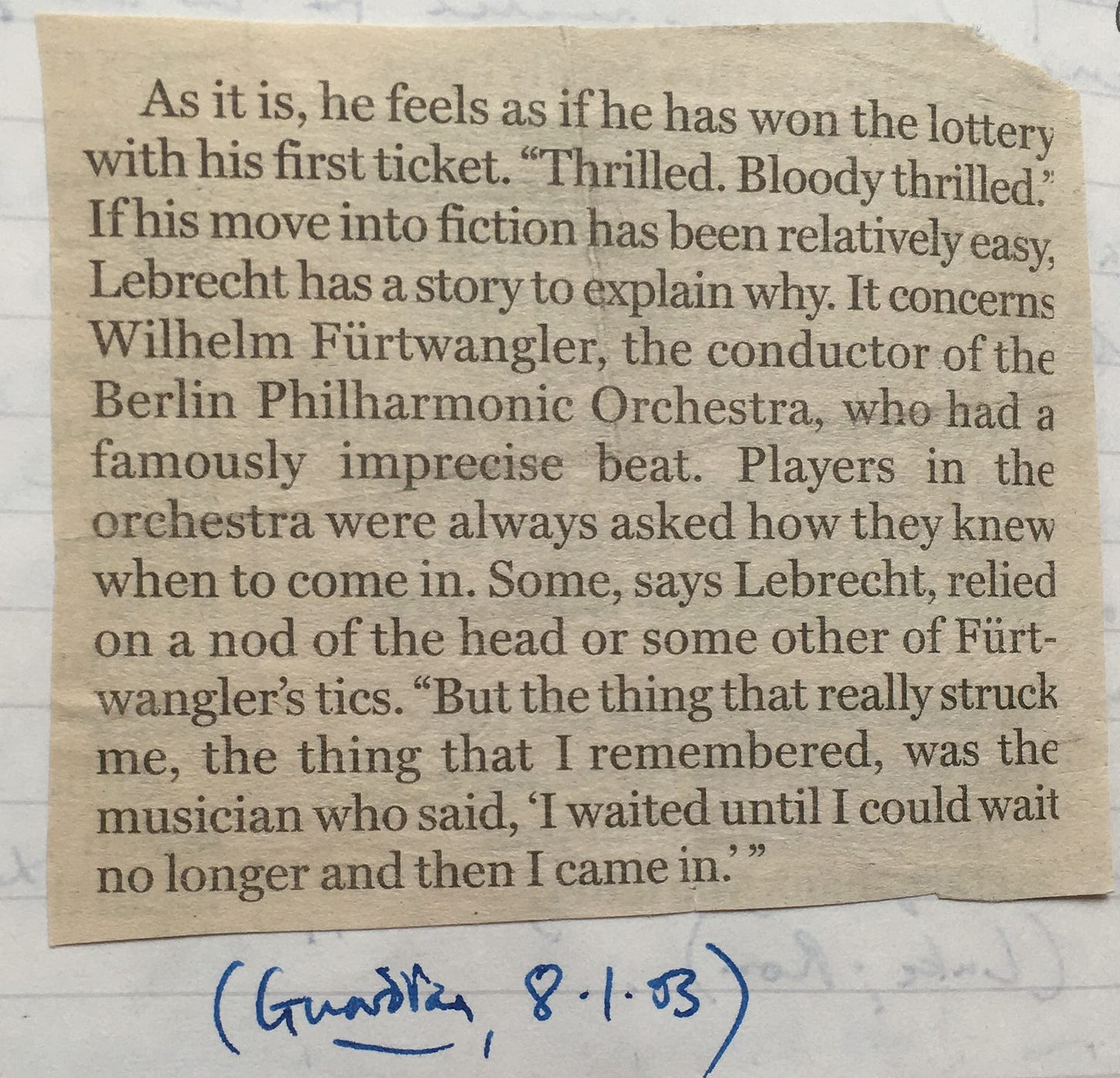

Most of the notes are hand-written but sometimes I’ve glued in a clipping.

What am I doing, when I write something in a notebook? Perhaps what I am doing is consigning a thought to the back of a drawer that I won’t have time or organisation to open again: note-taking as a version of throwing away. The overall impression on rereading this stack of records is a combination of (i) nothing having changed at all (these are all still my thoughts!) and, the direct and louder opposite, (ii) who is this stranger with these alien ideas?

What the notebooks demonstrate as a technology is a problem of mobility: these records are not alive, are not circulating, are not available for recall and recombination. They are inert and, very evidently as I read through the pages, often forgotten. How can noting be a mechanism for putting text in motion, rather than pinning text down?

One answer might be the kind of digital notebook software like Evernote (left) I’ve tried for 2 or 3 years (alongside, and overlapping uncertainly with, my paper books), but I’d much rather put my money on John Mellis’ A Briefe Instruction and Maner How to Keepe Bookes of Accompts After the Order of Debitor and Creditor, & as Well for Proper Accompts Partible, &c. (1588) (right). It’s possible you don’t know it. Mellis’ book is a guide for keeping financial records – how a Renaissance merchant can present an honest textualized version of his self to the world – but it might serve, as it did in early modern England, as a model for notebooks more generally.

For Mellis, notebooks are about transfer, revision, and refinement – about keeping records moving, shunting them round – and at the heart of his system is the construction of multiple, interconnected books. The dutiful accountant (let’s call him Ralph) begins by compiling a full inventory of everything he owns and all his debts, to establish a kind of ground zero. Then, in a second book, called the ‘Memoriall or Remembrance’ or sometimes a waste book, Ralph notes down business transactions as they occur, in real time. These records are scribbled franticly while the torrent of life comes at him – this is Ralph writing his 16th-century version of ‘shouting at the T.V’ or ‘compulsive eater’ – so they tend to be rushed, flabby, disorganised, inconsistent. Every five or six days, Ralph transfers this information to ‘his Journall’, where he pares down records to produce a leaner narrative, ‘without superfluous words’. Details like currencies are regularised; layout is made consistent. Finally, and meticulously, this information – ‘parcelles’, to use Mellis’s term – is carried over to the last book: the ledger, or ‘great booke of accompte’. Here, only essential details remain, and Ralph – happy Ralph! – brings a sense of regularity, system and clarity to his finances, and demonstrates his honesty, virtue, godliness, diligence, skill, and social credit.

There are a few notes of money owed in my notebooks, but they are not primarily financial records. But Mellis’ system of a network of notebooks, and of information revised-in-moving, might be a good model for note-taking more generally: the much-discussed bullet journal method from around 2013 effectively (without knowing about Mellis) combined these 4 or 5 books into one. Mellis’ system is one way of keeping information moving, and of turning writing into an act of launching.

At first sight, I thought you had stolen *my* notebooks. A second look, and I was pretty sure you had, except for the fact that my handwriting has improved, perhaps from being "laid up", like scotch in a barrel.

Here's an apposite item from a notebook I was keeping in 1978:

"Runaway thought, I wanted to write it; instead, I write that it has run away"

(Blaise Pascal, quoted by Roland Barthes, in 'Roland Barthes by Roland Barthes')

Mike

Brilliant read. I’ve often found the process of note taking to be more important than the actual product.

Mellis’ notion of the waste book seems to be reminiscent of how everyday rituals first become concretised before being embedded within the broader taxonomy of life.