Library stamps

In a hands-on ritual that has now largely been replaced by the beep of a bar code reader, borrowing a library book for many decades involved the stamping of a return date on a sheet glued to the front or rear inside cover. Additionally, a paper card was removed from the ‘lending pocket’, usually glued to the bottom left inside cover, and the borrower’s name was written in, and it was also stamped with the return date. When the book was returned, the stamped date was struck through, and the book card replaced in the pocket. A late return meant, usually, a fine.

As time passed, a book might accumulate a list of return dates, stamped often in different coloured inks, and with a level of careful placement that varied according to the librarian. Return date stamps were intended to serve a particular function – to remind the reader when the book was required back – but, like so many administrative records, they generate effects beyond their original purpose.

The years can flash by in these date stamp lists: they are seemingly neutral administrative documents shot through with pathos. When one date is followed by another date, something powerful happens. Where did the time go? Here is a copy of H.S. Bennett’s English books & readers, 1475 to 1557, from the Library of the Society of Antiquaries, with two stamps: 14 February 1985, and 22 February 2022.

So much seemed to happen in the 90s and noughties, but not here. We have two staccato moments in time: days of action for the book. These are issue dates, and return, we read, is required within 3 months. The dates are not a narrative, in the sense that the moments are not joined up: this isn’t a story of book use through time, but a record of 2 days when suddenly the book was required. It’s Valentine’s day in the mid-80s: get me H.S. Bennett’s English books & readers, 1475 to 1557! The gap between dates is the 37 years that Bennett’s book rested undisturbed on the library shelf, not waiting – can books ‘wait’? – but just … there.

This is a sparse account, a life of two moments, but stamps sometimes record frenzies of activity, a sort of social whirl. Here is David Norbook’s Poetry and Politics in the English Renaissance, from Balliol College Library in Oxford, experiencing a steady start to the 21st century which increased to a period of peak use ca. 2007-9.

‘Date Due’ declares the heading, so in fact the stamps mark not periods of use but the opposite: the days by which reading should stop, and the book should be returned. In this sense the list constitutes a kind of anti-travel account, a record of reading being disciplined: points in time when the book’s tendency to move around, to wander, to rest on new desks or in new hands, is curbed by the call to return home.

This copy of Brian Vickers’ Shakespeare, Co-Author was in and out the London Library pretty regularly between 7 February 2003 and 10 December 2018, with a fallow patch between 2013 and 2016: lean years for Vickers’ book.

Sometimes the stamp is imperfectly placed.

Sometimes the stamps have a playful, even carnivalesque quality. Here is Late Shakespeare, 1608-1613, edited by Andrew Power and Rory Loughnane, from the London Library, which has a single date, rather joyfully upside down:

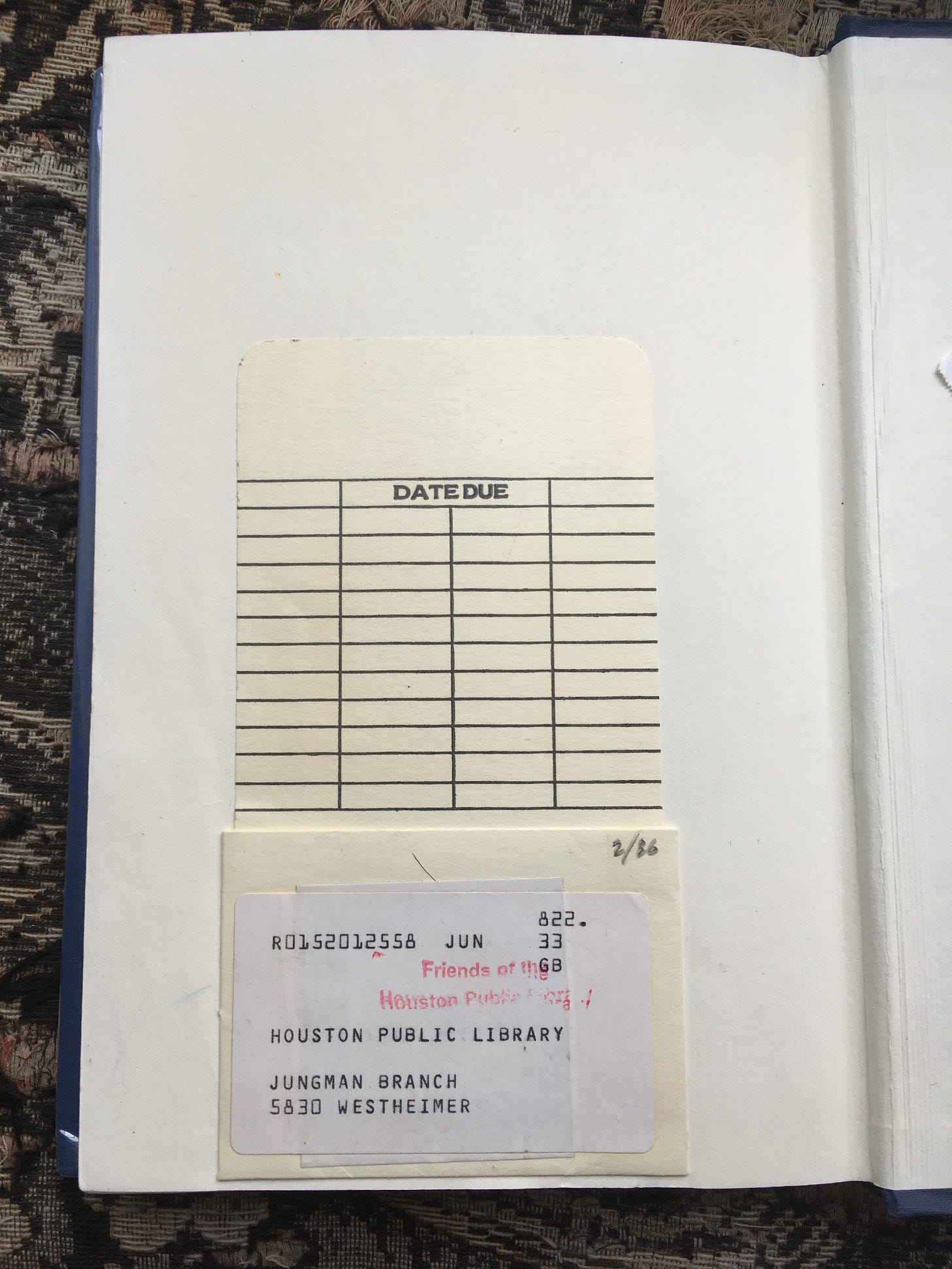

Quite often the form is entirely blank. This is Thomas Tanselle’s A Rationale of Textual Criticism from Houston Public Library:

Lists of stamp dates like this one might seem to tell a story of non-reading – and even for a busy book, moments of use are far out-numbered by moments of non-use. Library shelves are in this sense full of books not being read. But of course that’s the wrong way to think of things. What is so moving about a book is precisely its patience: the sense that H.S. Bennett’s English books & readers, 1475 to 1557 was there on the shelf, dead still, and the years became decades and the millennium turned and then suddenly the book is required, and here it is.

Hi Adam! Our library (now very advanced) began what then passed for computerization in the late 1950s, but a year or so ago I picked up a book in an area (rapidly dwindling) for really old books that hadn't yet been re-catalogued -- and discovered a card in the pocket at the back with my student signature on it -- 1953.

I enjoy puzzling over library stamps, too. And I've occasionally checked out a book in hopes of saving it from storage or culling! At the same time, I know that I've used many books that I never checked out. It's one of the terrible things about the computerised systems we have now; they seem to understand nothing about the presence of books. Now I have to order books so that I can look at them and decide they won't do. Or I order them and read one chapter, which I could have previously done in the library without checking the book out.