A few years’ ago, I asked for David Markson’s This Is Not A Novel for my birthday. My wife bought me This Is Not A Novel by Jennifer Johnston. David Markson’s This Is Not A Novel is a series of staccato fragments, a kind of commonplace book of literary history, delivered by a narrator called ‘Writer’ who presents an anti-narrative of literary deaths and gossip (‘Botticelli spent his last years on crutches’; ‘John Milton died of gout’ – I wrote about it here). Jennifer Johnston’s This Is Not A Novel is the story of Johnny, a brilliant young swimmer who might have made the Olympics, but who died young, 30 years ago. In 2022, Sandra Scofield published a collection of short stories called This Is Not A Novel, available on Kindle: a grandmother worrying she’ll be moved to a nursing home; an artist reflecting on youthful errors.

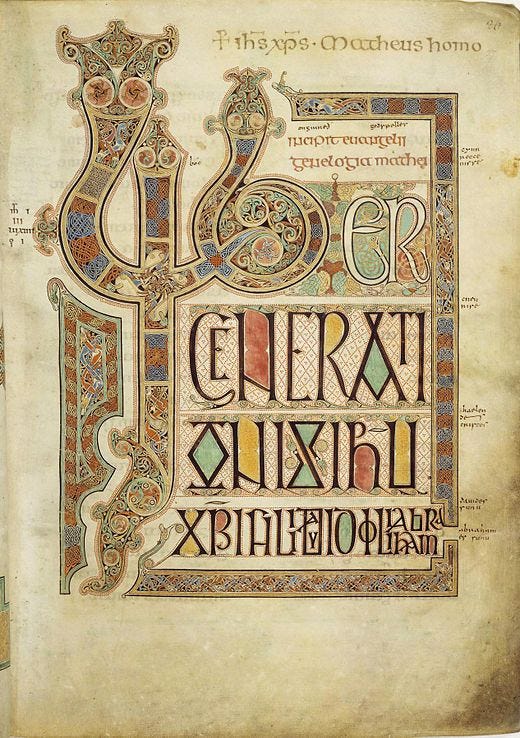

Titles seem obvious or self-evident as categories of writing, but they have a history as a form. Before print, manuscript texts began with an ‘incipit’ (Latin for ‘here begins’ or ‘it begins’): a brief statement that both announces the beginning of the text and declares its subject – like Incipit liber danielis (‘Here begins the Book of Daniel’). Incipits are interesting because they make the beginningness of titles part of the title.

Incunables (books printed in the infant years of print, before 1501, from the Latin incunabula, ‘swaddling clothes’ or ‘cradle’) had a brief title applied to the otherwise blank leaf at the start of the text – a blank leaf that was there to serve as a protective covering during the book’s transit. These titles were an improvised appropriation of a bit of available paper. By the 16th century, printed books began to present the title-pages we recognize today – like John Milton’s Paradise Lost, first published in 1667, and maybe (we can argue about this later) the best poem in English. In 2009, the popular historian Giles Milton published Paradise Lost, about the destruction of Smyrna in 1922. In 2022, Elizabeth Drayson published a history of Granada called Paradise Lost, and a year later, Paul Hogget wrote a book about the climate crisis which he called Paradise Lost. None of these should be confused with Lost in Paradise: A Billionaire Romance, by J.A. Low, published in 2022.

For the history of title-pages, I’d recommend Whitney Trettien’s ‘Title Pages’, in Book Parts, eds. Dennis Duncan and Adam Smyth (Oxford University Press, 2019), pp. 39-49.

And for the explicit: http://books-on-books.com/2019/04/23/the-colophon-and-the-left-over-i/ !

Funny, I've experienced with Markson a variation on this. I can't remember what had happened, perhaps the curriculum was changed a tad bit too late, but for one class I took in college some of the students were reading Markson's This is not a Novel, the others his Reader's Block.

I suppose that editor of Title Pages is not a mere relative?