Hands and books

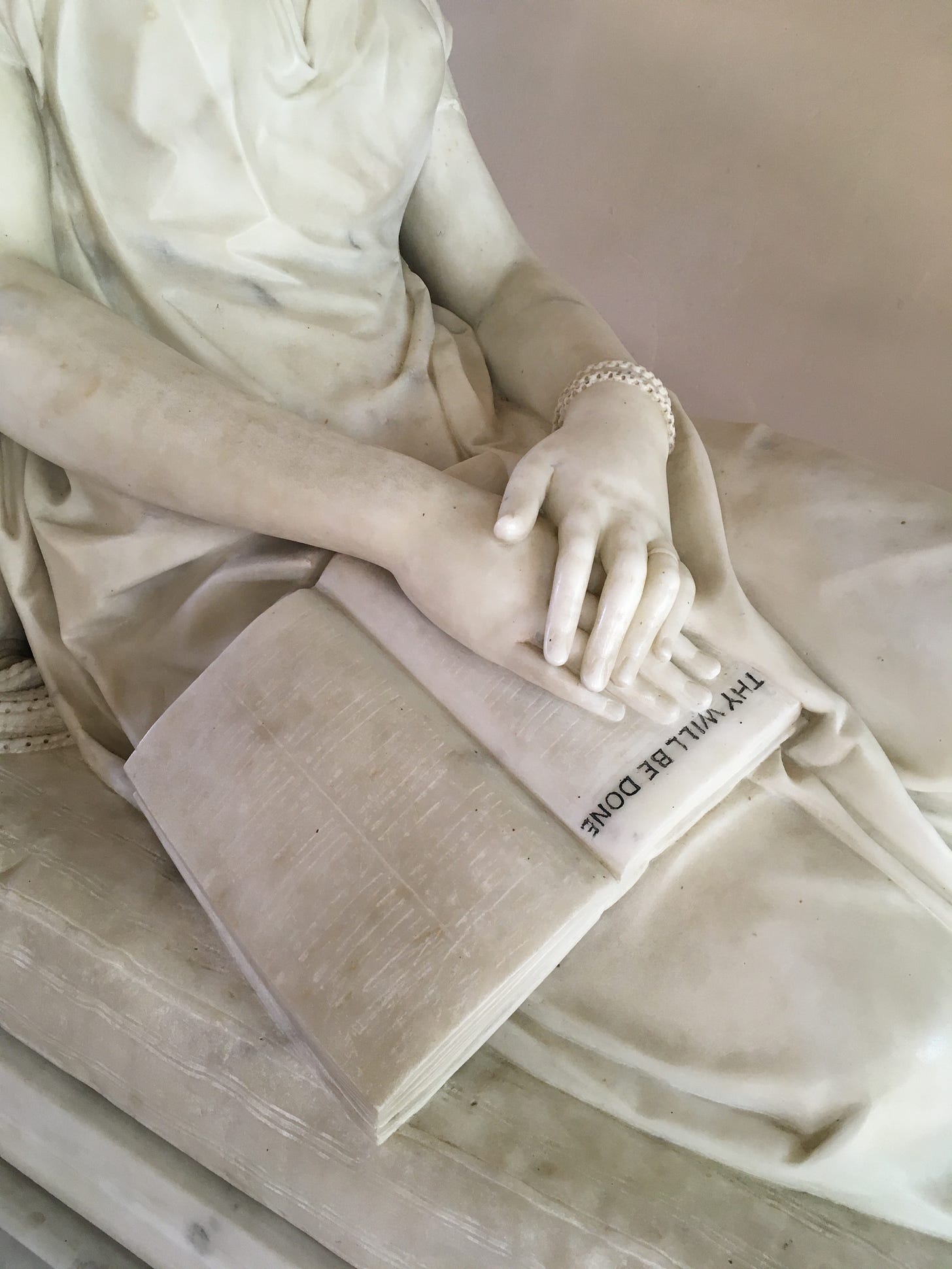

The village of Great Tew, Oxfordshire, was famous in the 1630s as a gathering point for intellectuals who, reclining in the comfortable surroundings of Lucius Carey’s estate, debated philosophical matters of the day. The whole place is pretty idyllic today, despite the continual rumours that Rupert Murdoch is about to buy the fallen-then-restored manor house. But my favourite thing about Great Tew are the hands of the marble sculpture in the wide chancel of St Michael’s Church of Mary Boulton née Wilkinson (1795-1829).

The memorial was carved by Sir Francis Chantry in 1834: the extravagant folds of Mary’s dress make it clear this is both a memorial to a young woman (Mary died young after the birth of her 7th child), and a chance for Francis to show off his skills. Death here is like sleep: we die as we nod off with a book in our hands. The hands are the focal point, the left holding the right in place as if to still its progress across the page, and to cover the text. Apart from the four words in black capitals from the Pater Noster, ‘Thy will be done’, the text is signalled by indentations that denote letters but, on closer examination, are illegible.

They are writing-like marks, not writing, and their unreadability keeps us from coming too close, both in terms of the sculpture as a work (so we stand back and observe the whole), and in terms of Mary’s subjectivity (we can no longer share what she has been reading: she is locked out to us).

Some different hands. These belong to biographer Lytton Strachey (1880-1932) in a portrait by Dora Carrington. In fact they are hardly hands at all, more collections of gathered fingers, held in a pose so striking that you feel it must be documentary: the left thumb and forefinger forming a ‘c’, the right fingers resting on the book more than holding it, like sticks or lined up pencils.

Here’s a photograph of him.

We don’t know who took it, but Strachey here is being paradigmaticly Lyttonic: not one but two deckchairs, with a third on standby, and objects (large floppy hat, umbrella) gathered but not used. He’s in the garden of Asheham House, Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s weekend house near Lewes, Sussex, around 1915 – the fingers once again grasping and also framing, holding the magazine as if the pages vibrate and need pinning down.

One consequence of Strachey looking so particular is, ironically, that lots of people look like him. Here is his near double in 1541.

Giovanni della Casa (1503-56) was a Florentine poet and author of the enormously influential conduct book, Il Galateo overo de’ costume (1558). Don’t clip your nails in public; don’t talk about dreams ‘since most dreams are by and large idiotic.’ He’s painted by the Italian Mannerist Jacopo da Pontormo. There are no deckchairs but there is a Strachey-like stretching to everything: the head, the nose, the beard, the body, the hands, even the windows. The book is held close, away from us – we threaten intrusion – and the job of the fingers is to mark where the reading paused, and where it should resume. In fact the fingers register two places in the book, and della Casa – humanist scholar that he was – may have been in the process of comparing different passages. The book is unidentifiable. It’s not Il Galateo, which wasn’t published for another 17 years, but its small format suggests portability and ease of use. Perhaps it’s one of the elegant publications of the Aldine Press in Venice: Aldus Manutius’s publishing house, founded in 1494, became famous for the small ‘handbook’, or enchiridion, from the Greek within (‘en-‘) and hand (‘kheir’), something held and contained within the hand.