A brief experiment in cutting up poetry.

I wondered what would happen if I tried to patch together an Edmund Spenser poem using William Shakespeare’s words: if I cut out words from Shakespeare’s Sonnets, published in print by Thomas Thorpe in 1609, and used these to recompose a Spenser sonnet, published in print by William Ponsonby in 1595. Would I learn anything?

Here is the Spenser poem I chose: sonnet 74 from Spenser’s Amoretti, a poem normally understood to describe Spenser’s love for three Elizabeths (his mother, Queen Elizabeth I, and his second wife Elizabeth Boyle). I chose it in part because its first line hinted at my method (‘most happy letters fram’d by skilfull trade’).

I used a full text database to find where, in Shakespeare’s sonnets, each of the words in Spenser’s poem appeared. Here, for example, is my annotated version of Spenser’s final line, with a note of where each word appears in the 1609 Shakespeare sonnet sequence:

that [sonnet 5, line1] three [104.7] such [9.14] graces [17.6] did [31.11] unto [47.2] me [49.6] give [51.14].

This gave me a map for finding Spenser’s words inside Shakespeare’s sonnets. I printed out a text of the 1609 sonnets, and located, and then cut out, each word, one by one, working through Spenser’s poem in a strange, slow, parody of reading, gluing the words onto a page.

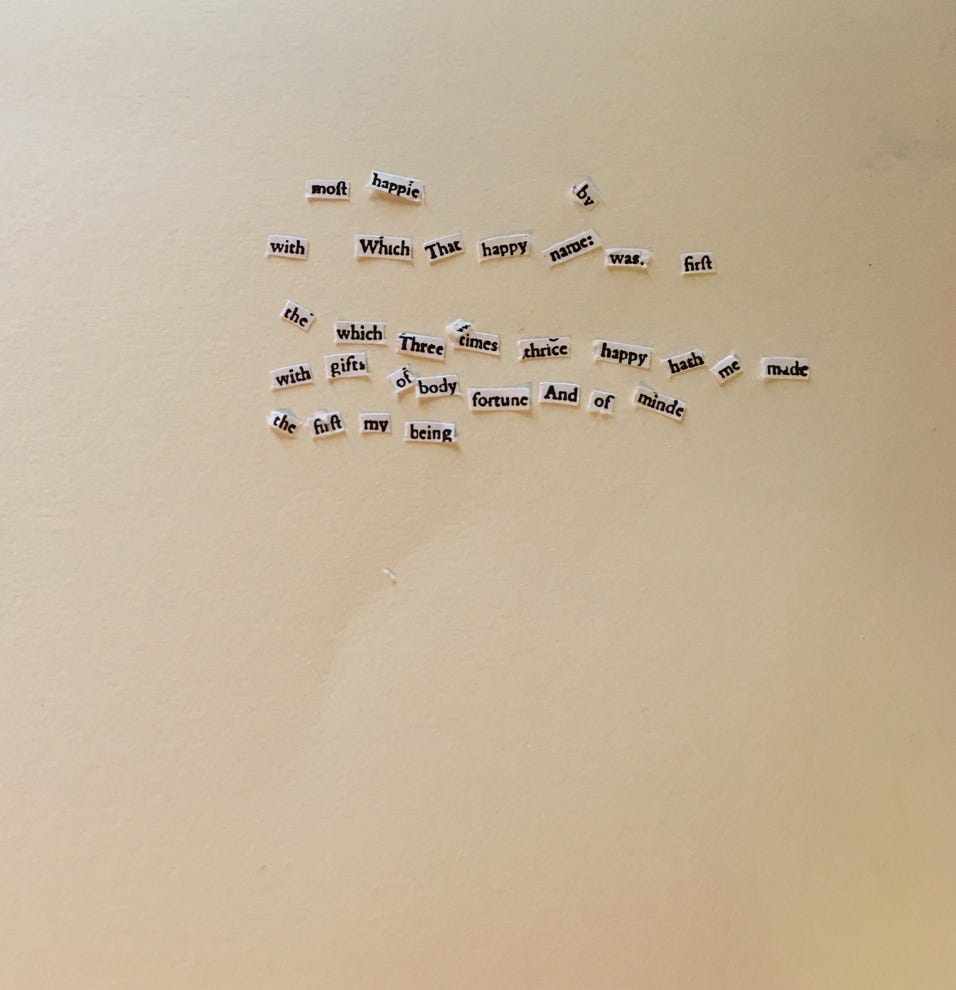

Spenser’s poem gradually pulled itself together out of these cut-out words from 1609, as you can see here.

And eventually, I had this: part ransom note, part 1630s Little Gidding Harmony, part Sex Pistols album cover – but all of Spenser’s poem, made from Shakespeare’s words.

I also had a by-product which I hadn’t thought about at the outset: the tattered version of my print-out of Shakespeare’s sonnets, with holes where I’d cut out Spenser’s words. You can see some of these here: an accidental erasure poem, or Shakespeare redacted by Spenser.

Here are these cut pages from the back, looking like a tower block at night:

What does this tell us? What do we learn about Spenser, or Shakespeare, or writing more generally, when we have as our tool not pen or pencil or tablet or laptop, but knife, scissors, and glue?

All but 11 words in Spenser’s sonnet appear in Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence. You can see the 11 words that don’t appear in Shakespeare’s sonnets below, in bold italics. (When I couldn’t find these 11 words in Shakespeare’s sonnets, I turned to his plays, and cut these out to use.)

Most happy letters, fram'd by skilful trade,

With which that happy name was first design'd:

The which three times thrice happy hath me made,

With gifts of body, fortune, and of mind.

The first my being to me gave by kind,

From mother's womb deriv'd by due descent,

The second is my sovereign Queen most kind,

That honour and large richesse to me lent.

The third my love, my life's last ornament,

By whom my spirit out of dust was raised:

To speak her praise and glory excellent,

Of all alive most worthy to be praised.

Ye three Elizabeths forever live,

That three such graces did unto me give.

These anomalies are interesting: it’s surprising that Shakespeare’s sonnets don’t include the words ‘skilful’, or ‘trade’, or ‘forever’, or – almost unbelievably – ‘letters’ (a word that is everywhere in the plays.) This is the kind of negative research question that’s usually hard to formulate – what words does Shakespeare not use? – but cutting brought this into the light. Only one word in Spenser’s poem was nowhere in Shakespeare’s canon: the plural ‘Elizabeths.’

It was a slow, and fiddly process, that couldn’t be hurried. I came to think of words in different ways. I was worried the little papery slips would blow away – as they nearly did, at one point, as you can see here.

I became aware of words as visual units, as pieces, rather than semantic content. I started to notice that there were shorter words inside longer words: that the word ‘ornament’, for example, has the word ‘name’ in the middle.

The cut out words, glued down on the page, sometimes carried with them evidence of their original context: glimpses of former lives with adjacent letters, or shifts in type (the capitalised F and R in ‘from’) that signal something about the word’s original position in the 1609 sequence.

So there is some sense of these words, as the constitute Spenser’s poem, recalling their origins, and once I felt that, I began to wonder whether these words bring with them, into Spenser’s poem, some of their original connotations. The word ‘derived’, in line 6 – ‘From mother’s wombe deriv’d by due descent’ – comes from the opening scene of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where Lysander defends the status of his genealogy to Theseus: ‘I am, my lord, as well derived as he’. Is this scene, or a trace of this scene, brought into the poem?

Even if we don’t know the precise origin of these words – and I’m thinking of origin here not as etymology but as prior placement on the page – the sense that these words come from elsewhere is worth thinking about. Patching together Spenser’s poem is a reminder not only that books are inevitably intertextual – they grow out of other texts – but more fundamentally that all writing involves selecting words from a finite pool. Some technologies, like the typewriter, make this sense of writing as selection vividly apparent: writers may create an infinite number of worlds, but the next action can never be more than choosing one from a small number of keys. The pen and the blank page create the illusion of creativity out of nothing: but searching, cutting, pasting, helps us understand writing as the act of choosing pieces from a constrained group of words.

A version of this post was originally a brief talk on a panel on creative criticism given at an International Spenser Society meeting: thanks to them, and to Dennis Duncan for clever digital advice.

Actually, to the older IT-trained eye, the cut pages from the back resemble not so much a tower block at night as an 80-column punched card, from the days when even computer data was paper-based. I doubt there's much creative mileage in running a sheet through a reader though, assuming you could even find one, although it might be a way of revisiting your "Pins through paper" adventure.

Mike

Fantastic. Seems to me as a coexistence of map and territory, which potentially could move back and forth (is Shakespeare the map, is Spenser the territory?).

But the first thing came to mind, was the way Tristan Tzara instructed how to make a Dadaist poem (1920):

• Take a newspaper.

• Take a pair of scissors.

• Choose an article as long as you are planning to make your poem.

• Cut out the article.

• Then cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them in a bag.

• Shake it gently.

• Then take out the scraps one after the other in the order in which they left the bag.

• Copy conscientiously.

• The poem will be like you.

• And here are you a writer, infinitely original and endowed with a sensibility that is charming though beyond the understanding of the vulgar.