A colophon, from the Greek for ‘summit’ or ‘finishing touch’, is a short piece of text, typically at the end of a book, giving details of some combination of the book’s date and place of printing, and sometimes the name of the printer or publisher. Here is a characteristically loquacious and also punctual example from Wynkyn de Worde, at the end of a book he printed (we read) on 23 March 1509:

By the start of the sixteenth century, most colophons had migrated from the final page to the foot of the title-page to become the imprints that look a bit more like imprints in books today. Here are a couple of early modern examples. This is the imprint from A Pleasant Conceyted Comedie of George a Greene, the Pinner of Wakefield:

In this example, Stafford has printed the book for the publisher Cuthbert Burby – a man who had his fingers in many bibliographical pies – and the books are available wholesale at Burby’s shop near the Royal Exchange (close to today’s Bank underground station). Here is the imprint for Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II, in an edition from 1622:

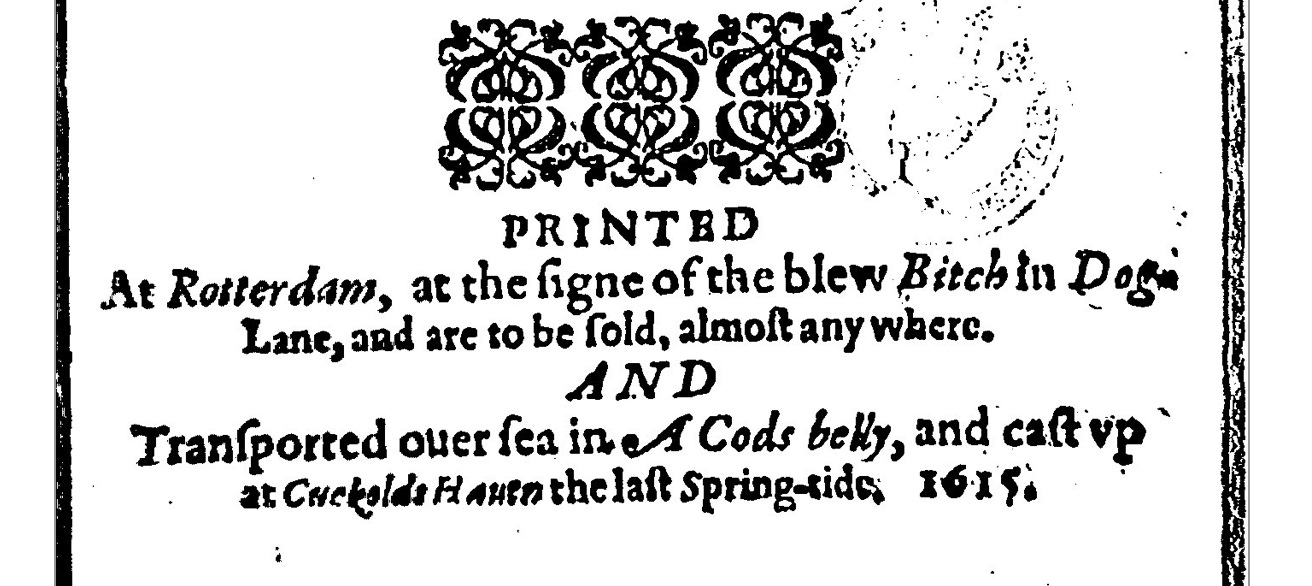

Bibliographers have built a whole discipline on these little chunks of text, drawing from them data about printers and dates and places of publication, even though the information is often inaccurate and incomplete. In the 17th century, authors sometimes responded to the legalistic imprint by playing around with its conventions, treating the imprint less as a sturdy piece of documentary history and more as a form to be exploited: dragging the imprint into the swirl of the text. The poet and waterman John Taylor (1578-1653) was the master of this kind of paratextual larking around. Here is his Taylors Revenge (1615), a book in which he attacks rival poet William Fennor for failing to show up for public poetry duel:

And here is a text from 1589 mocking priests and church hierarchy, written by an anonymous puritan writer styling themselves ‘Martin Marprelate’, printed on an unlicensed press with a correspondingly false, and satirical, imprint:

(These and other kinds of playful imprints are explored by Helen Smith in Renaissance Paratexts (2011), edited by Helen Smith and Louise Wilson.)

Les Coleman (1945-2013) was a writer, artist and collector who explored the nature of the book and the page. He is perhaps best known for Glue (2002), in which each page spread is stuck together with a different type of glue, as listed in the table of contents: the book is unyielding, physically, and the only way to ‘read’ conventionally, page by page, is to tear the thing apart.

There’s a different kind of unyielding in Coleman’s Another Book, originally published in 2012 by Coleman’s In House Publishing in a small edition of 50, but republished in 2022 by Uniformbooks. Another Book is a collection of imprints, with details of title, author and location removed. Here are a few pages.

Book historians conventionally distinguish between ‘text’ and ‘paratext’ – the latter the surround, like the title-page and footnotes and index and dust jacket, that ushers the text into the world. But Coleman’s book is all paratext: it is a book without a centre. It is a series of imprints, each cut off from the object they index. One of the effects of Coleman’s book is to make us return to his book’s actual imprint with a heightened sense of the form. Another, as Elizabeth James rather brilliantly observes, and as Coleman’s title registers, is that Coleman’s work reminds us that ‘most books are another – edition, impression, reprint or translation’.

For more on the history of imprints and colophons, there is Shef Rogers, ‘Imprints, Imprimaturs, and Copyright Pages’, in Book Parts, ed. Dennis Duncan and Adam Smyth (OUP, 2019).

A book of paratexts sounds like my kind of book! Thanks for this wonderful post! Reading it made me wonder about the paratexts of digital writing (like substack). Would you consider the copyright note at the bottom of ss posts an imprint?