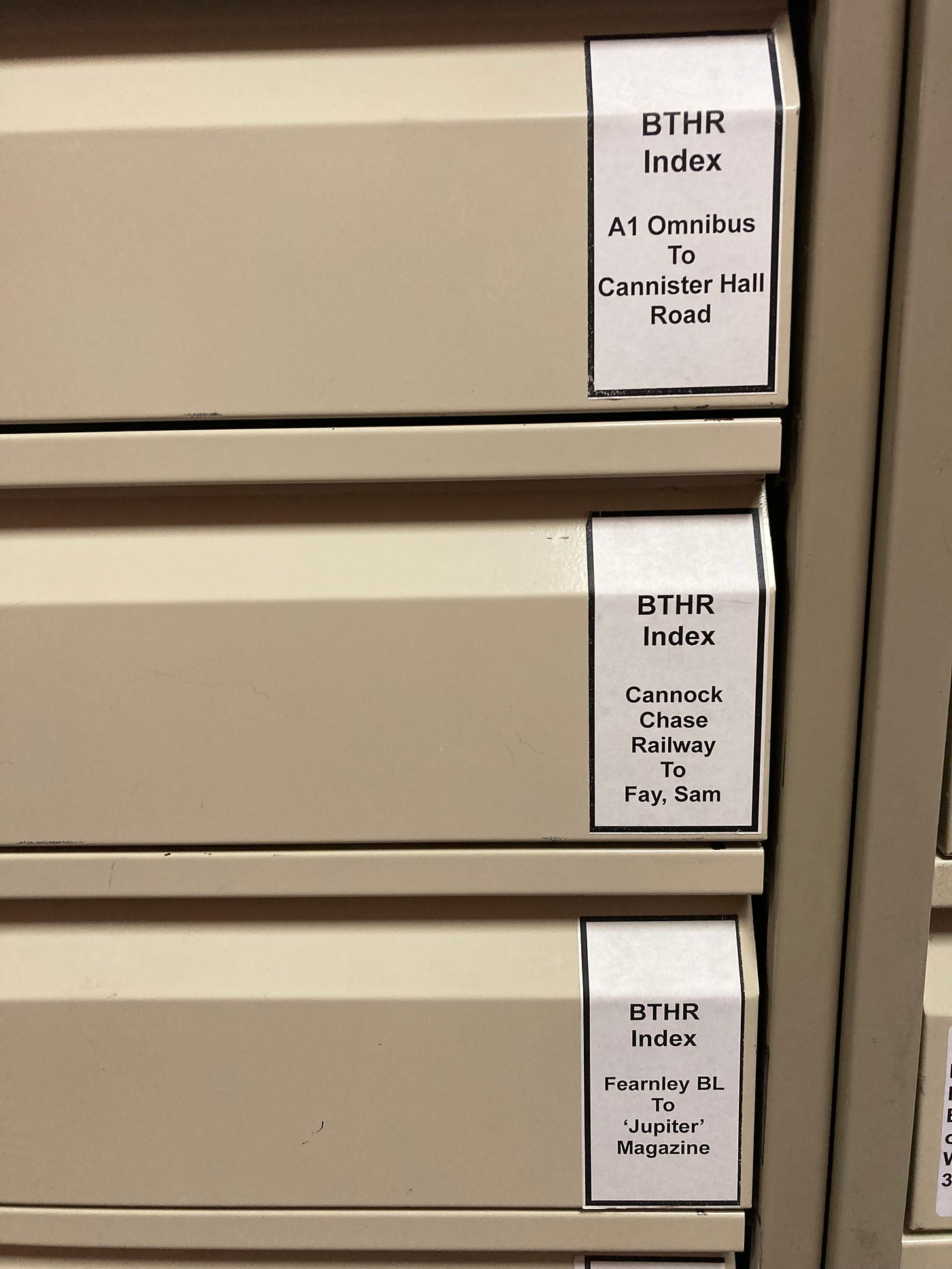

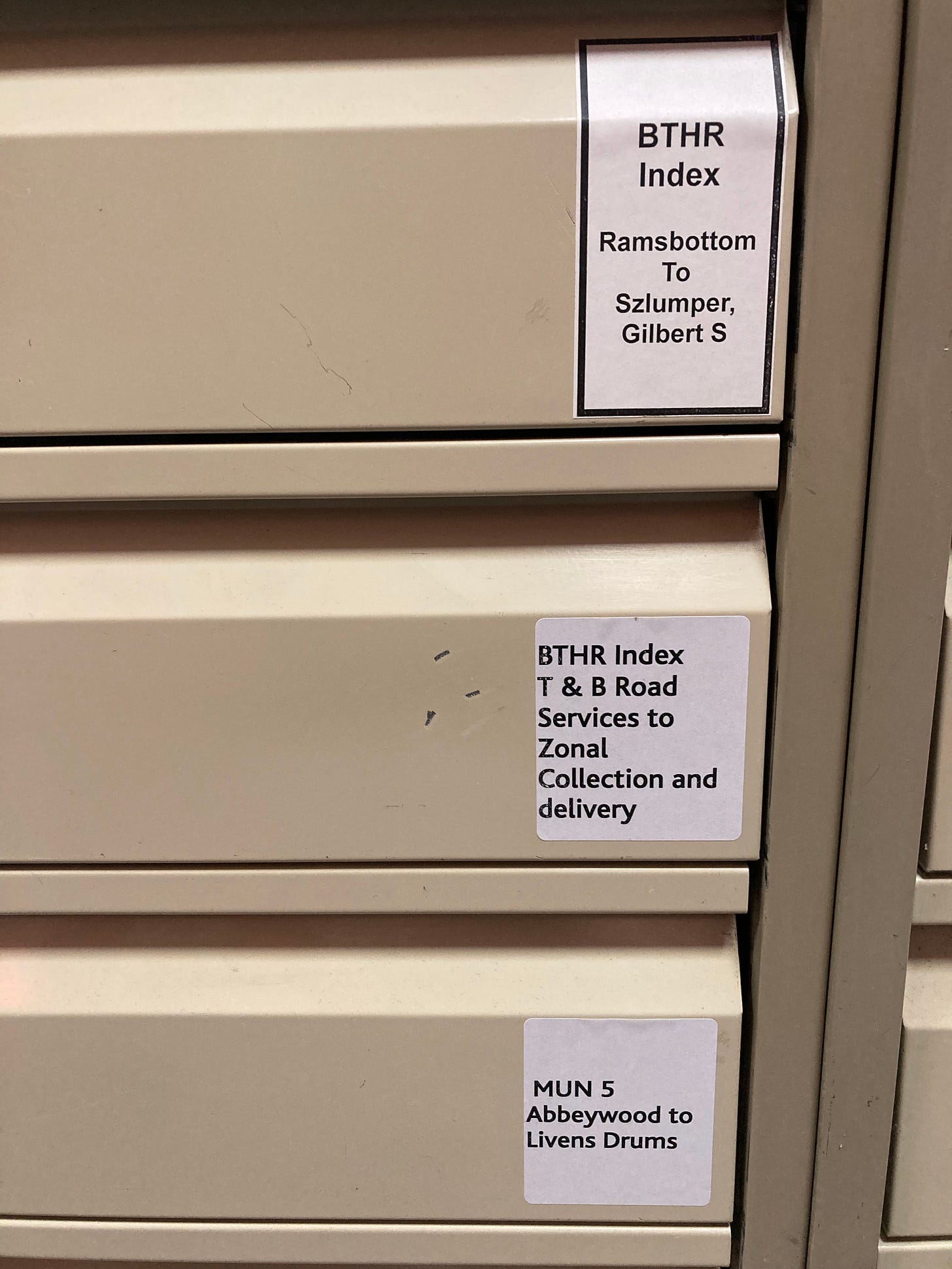

On my way to the reading room in the National Archives in Kew, I see a set of filing cabinets that carry headings of implausible exactness.

There is something immediately joyful about ‘Cannock Chase Railway to Fay, Sam’ -- in the baffling inclusivity of these ‘from X to Y’ headings. I stop and look at the others.

These contents have clearly been gathered with some idea of order – I realise after a while that ‘BTHR’ stands for British Transport Historical Records – but the topics, in their exactness, seem to pull away from this idea of containment. I start to think of these metal filing cabinets at tardis-like structures, with insides vaster than their outsides, in order to accommodate all these particulars.

The most famous version of this tension between gathered items and hyper-specificity is Jorge Luis Borges’s fictional taxonomy of animals in his 1942 essay ‘The Analytical Language of John Wilkins’. Borges quotes a ‘certain Chinese encyclopaedia’ in which ‘animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the Emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) suckling pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.’

The philosopher Michel Foucault liked Borges’ list – and opened his Order of Things (1966) with it – because it suggested to him an entirely other system of thought, and so a sense of ‘the limitation of our own.’

Lists of library shelf marks are good places to find similar effects. Here are the subject descriptions deep in the 1890s stacks, with their iron-grille floors, in the London Library, on St James’ Square. The 17 miles of books are organised alphabetically by subject (and then, within this, by author): the arbitrary nature of alphabetical order produces and refuses a sense of pattern and sequential meaning. (In contrast, the Dewey Decimal system positions categories on shelves in relation to other categories on similar topics.) This series of sudden juxtapositions has all of the joy of Borges’ list:

I wonder what lies behind subject headings like "fingerprints," "fireworks," or "forestry."

This brings to mind Timothy Shipe’s thought-provoking article, "The Librarian and the Artist's Book: Notes on the Subversive Art of Cataloging." In the article, Shipe recounts the misclassification of Ed Ruscha’s artist's book, “Real Estate Opportunities” (1970). At that time—over a decade before the Library of Congress officially recognized the term “Artists’ Books” as a subject heading—Ruscha's work, which consists of photographs of lots for sale in Southern California, was incorrectly categorized under the subject heading “Real Estate Business.” Although Shipe considers this an “understandable mistake” that was eventually corrected, he offers a different perspective on this unintentional act. One key characteristic of avant-garde art is its ability to challenge, disappoint, or subvert audience [readers/viewers] expectations, rather than simply fulfill them.

If you ever visit a library that uses the Library of Congress classification scheme (many British university libraries do) ask whether they still have printed copies of the "schedules", possibly the most entertaining and educational volumes I have ever had the pleasure to use... Pretty much everything is in there, like an inventory of human knowledge, constantly expanding with new stuff slotted into convenient (but not necessarily logical) gaps. All the right notes, but not necessarily in the right order...