What does it mean to place one book next to another? What connections does this kind of piling up suggest? My shelves are usually (a) quite messy, and (b) a register of sequence. Here is a recent pile on a shelf whose verticality tracks what I read, in order, for some of 2019-20.

And here is a run from around 2018:

This is a register of books through time, but there are all kinds of other possible connections, too. Literary criticism’s most fundamental manoeuvre is to place one text next to another and to track connections between the two. Bookshelves invite interpretation-by-propinquity on a physical level. Joshua Eckhardt’s brilliant Religion Around John Donne (2019) shows how, in bookshops and on library shelves, the placement of Donne’s texts next to other texts can open up new ways of reading. (Izaak Walton’s copies ofJames I’s Works and Donne's LXXX Sermons are now shelved alongside one another at Salisbury Cathedral Library (R.1.13 and R.1.14).) Implicit in my shelf above is a series of comparative readings, some more plausible than others: Ann Quin in relation to Jo Shapcott (interesting?); Sally Rooney and V.S. Naipaul (possibly?); Horace Walpole and Geoff Dyer (definitely not?).

My favourite bookshelf painting is the huge oil-on-canvas triptych, commissioned by Lady Anne Clifford (1590-1676) to give expression to her 40-year legal battle to reclaim her Westmorland and Yorkshire family estates. It’s 2½ metres high and 5 metres wide, and probably the work of Flemish artist Jan van Belcamp, and uses a three-section format associated with religious works to represent a trio of scenes from Clifford’s life.

On the left, Clifford is 15, her eyes locking our gaze at the moment of disinheritance. In the centre, we’re back in 1589: Clifford’s parents hold their open hands towards their eldest child, presenting to the world not only a son but also the triumphant logic of primogeniture. Clifford, here, is an absent presence, in utero; both boys would die soon after. On the right, it’s 1643, and Clifford is 53, and she’s regained her family estates after a life (in Barbara Lewalski’s words) ‘engaged in an almost mythic battle, against mighty odds and against every social pressure’. The painting hung in Clifford’s Appleby Castle for 300 years; when it was moved to its current location, Abbott Hall in Kendal, Cumbria, the central panel was too large for the doors and had to be craned into the building through a window.

It’s also a painting about bookshelves.

Clifford wrote that she ‘made good books … [her] companions’, and behind the teenage Clifford on the left are shelves of neatly stacked volumes that, in offering the promise of particular titles, draw us in. There’s a Bible, prominent with green spine, and Augustine’s City of God, and also secular, literary works of the sort you’d find today on an undergraduate English Literature reading list: Philip Sidney’s Countess of Pembroke’s Arcadia, Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Sir Thomas Hoby’s translation of Castiglione’s The Courtier, Thomas Shelton’s translation of Don Quixote, Florio’s Montaigne, and works by Edmund Spenser, Chaucer, and Clifford’s tutor Samuel Daniel. In The Common Reader, Virginia Woolf said Clifford ‘read good English books as naturally as she ate good beef and mutton.’ (Idea: next year’s Renaissance Lit module to be taught using this painting as the reading list).

The 22 volumes on the right announce a change of tone: poetry by John Donne and drama by Ben Jonson jostling with more obviously sober works – sermons by Bishop John King, works of devotional or moral philosophy, histories by Plutarch and Guicciardini. And jostling is right. Tracking across panels, we see a representation of something like bibliographical entropy, as 15-year-old Clifford’s tidy volumes become the ramshackle piles of the 53-year-old. Is this Renaissance shelf-fashioning? What do disordered books represent? Reading? Use? Relevance? Irrelevance? Engagement? Abandonment? The two sets of shelves announce some kind of contrast, suggesting something has changed: between books as prospect, perhaps, and books as read, and this bibliographical before-and-after painting asks us to shift between the two. The Great Picture, as the whole thing is called, was produced in 1646, so Clifford on the right was the only figure painted from life (the rest copied, as was van Belcamp’s style, from miniatures, portraits, and objects still in Clifford’s possession). The disordered books, along with the leaping dog stilled mid-air, are perhaps one way of conveying the nowness of this panel: a tumble of books signifying an eternal present tense.

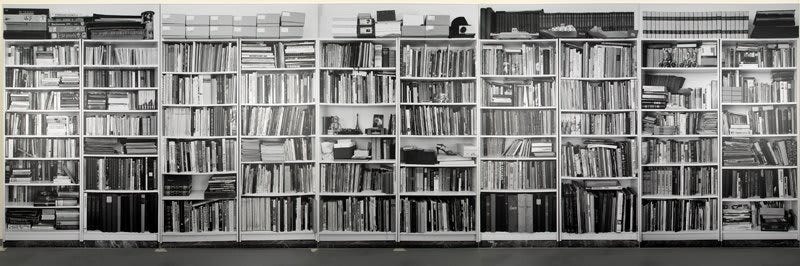

Clifford’s back-and-forth shelves find a still answer in Hans-Peter Feldmann’s (b. 1941) life-size black-and-white photograph, also composed of panels, of the densely-filled shelves in his Düsseldorf home. It’s about the size of Clifford’s Great Picture, which means Feldmann’s photograph is the same size as his actual bookshelf: maybe we think for a moment we’re in front of a bookshelf, rather than a photograph of a book shelf, and we reach forward to pull out a volume. But the photograph – for all of its promise of revelation, intimacy, reading – serves only to lock us out.

The end-point of bookshelf art work may well be Andreas Gursky’s nightmarishly inclusive photograph of thousands of boxes of ready-to-be-shipped orders in an Amazon Centre in Phoenix, Arizona (2016).

Books here are all physical object; that link we like to imagine between books and individual subjectivities is cruelly parodied in the rows and rows of coloured objects, and the ejection of all people from the scene becomes louder and louder the more we look. Where is everyone? Books have taken over the world! But for all its epic scale this is also a deeply tentative image: the promise of despatch hangs in the air, and if this is a vast still order of books, it is only for the time being. They are imminently on the move, and the photograph is an image of bibliographical order about to be radically scattered.

One more. I love Wang Qingsong’s C-print Follow Him (2010): a lone reader surrounded by packed shelves that seem never to stop.

Qingsong collected used books and magazines from the streets of Beijing, placed them on shelves, and then let dust gather for a year. The artist, appearing as something like an academic, or an absorbed autodidact, or a reader desperately trying to catch up, is a human interloper in a scene that is almost all-book. He sits behind the piled-high desk, surrounded by a madness of shelves and also discarded pieces of paper that seem to represent not only some variety of writerly failure, but also, as they accumulate, a kind of anti-shelf.

Bookshelf reading:

Jamie Camplin and Maria Ranauro, Books do furnish a painting (Thames & Hudson, 2018)

Joshua Eckhardt, Religion Around John Donne (Penn State University Press, 2019)

David Trigg, Reading Art: Art for Book Lovers (Phaidon, 2018).

Wang Qingsong’s "Follow Him" looks remarkably like Aardvark Books in Brampton Bryant, a mandatory visit we make on our annual Easter trip to the Welsh Marches, as we did this last week, this time masked and wearing the supplied surgical gloves. Which would probably be a good idea in most second-hand bookshops at most times, now I come to think of it.

I miss the old Thornton's Bookshop on Broad Street, where treasure could be excavated from filthy cardboard boxes stowed beneath the staircases, still priced in shillings and pence. That was a *proper* bookshop, straight out of central casting.

And aren't those IKEA Billy bookshelves in the Clifford triptych? Apparently a set has been sold every second since the Reformation.

Mike

Interesting that the labelling of Clifford’s books is a constant in all three panels. Labels appear on the books turned fore-edge out and, on those shelved spine out, always at the top of the spine. Even more interesting that, among the third panel’s jumbled books, the labels appear on the bottom or top edge of books turned spine down. Is that the painter’s doing or Clifford’s? Were the labels folded pieces of paper not glued down but movable to show, depending on how the book was shelved? If so, and if it was Clifford’s doing, what a personality to insist on order within her disorder. Two more sites for bookshelf sightings: https://www.onthebookshelf.co.uk and https://bookpatrol.net/?s=bookshelf. Cheers, Robert