A book has been left on a wall, open to the elements, near where I live: Tilly Bagshawe’s Adored (2005), the story of Sienna McMahon, granddaughter of movie legend Duke McMahon, who grows up amid scandal. ‘Sex. Greed. Ambition. Welcome to Hollywood.’

After three, four, five days, the book is still there. We tend to think of books joined to readers, but for almost all of their lives, books are not being read: they sit in rows in book shops, or on shelves in a home, or in libraries or archives or off-site storage rooms, or packed up in boxes in garages, waiting for someone, against the odds, to pick them up. I have books that I’ve not opened for decades. And while there is a magic in that latency, and in books’ wonderful long-termness – they are so patient! – one overlooked consequence of the invention of printing, as Hugh Amory once noted, was the creation of huge numbers of books that were never read. This is a truth that doesn’t quite square with the stories we tell about how essential books are. Sometimes books are unopened for years, or forever. At the Bodleian and the British Library, I’ve quite often ordered up 16th or 17th-century volumes which arrive with uncut (more correctly, unopened) pages, meaning they have never been read. Should the pages be cut now, to reveal the contents, or are these books valuable for their time-capsule sense of having-arrived-just-from-the-printers?

There are countless paintings of acts of reading, but there are also many of books without readers. The copy of Bagshawe’s Adored on the wall reminds me of François Bonvin’s Still Life with Book, Papers and Inkwell (1876), particularly in the way the covers of each book lie slightly open — in Bagshawe’s case because my (unidentified) neighbour has evidently read the book before; in Bonvin’s painting because of a pair of pince-nez glasses serving as an improvised bookmark.

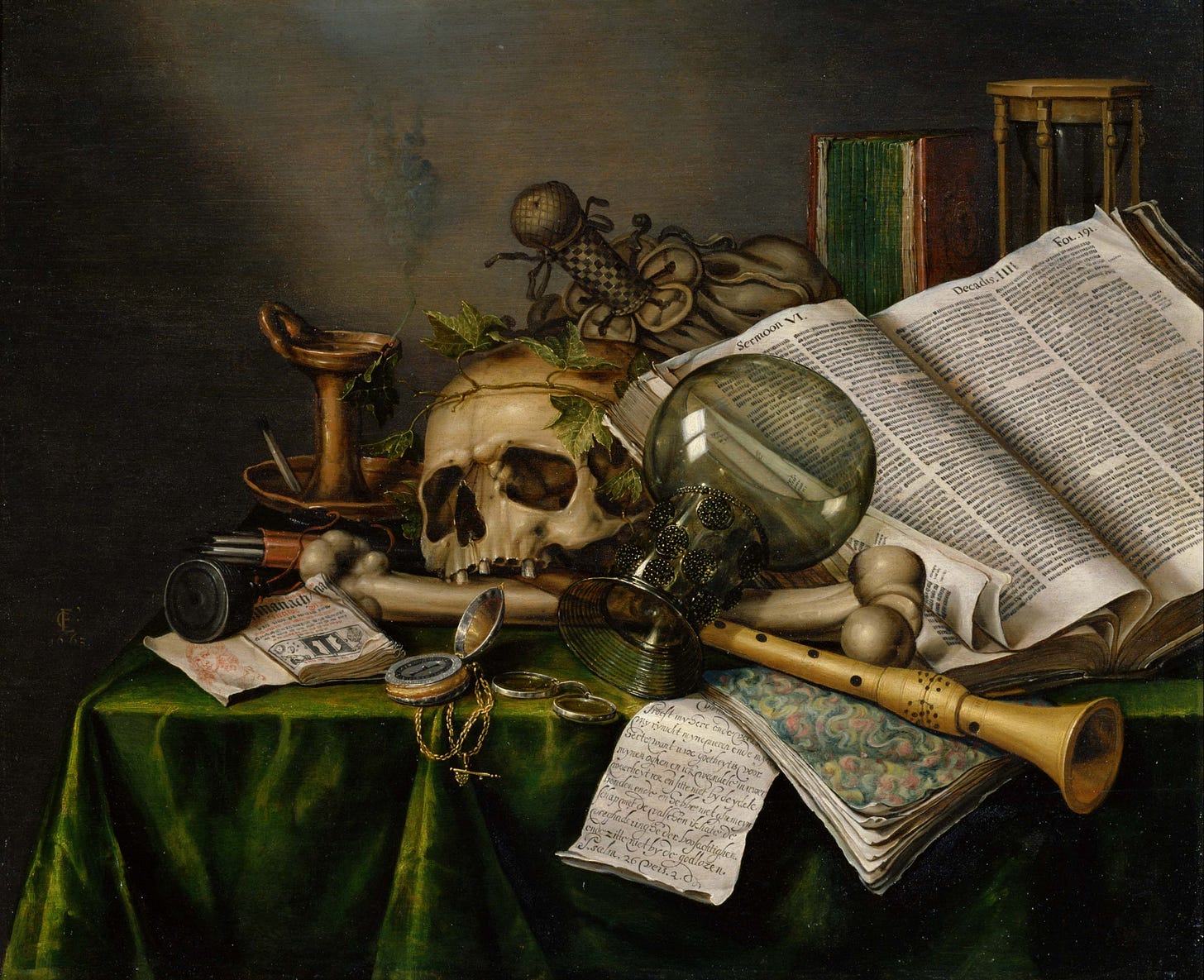

Bonvin, working in nineteenth-century France, was interested in Dutch and Flemish 17th-century painting, where still life works often expressed a 'vanitas' theme: piles of objects, beguiling and beautiful, as warnings of life’s brevity. Edwaert Collier’s Still Life with Books and Manuscripts and a Skull (1663) is one representative example, and books feature among the many objects that tell us of the transience of life, and of the inadequacy of attachments to worldly stuff.

A painting like Collier’s is complicated, not least because it necessarily celebrates the objects we are being warned about: we grow attached to the green tablecloth, and the musical instrument, and the glass, even as we are counselled to jettison those things. The painting itself also becomes an instance of the kind of lavish object we should turn our gaze from (today it’s in Japan’s National Museum of Western Art). As viewers, we are dependent on these objects for this lesson; but the lesson is to stop paying attention to these objects.

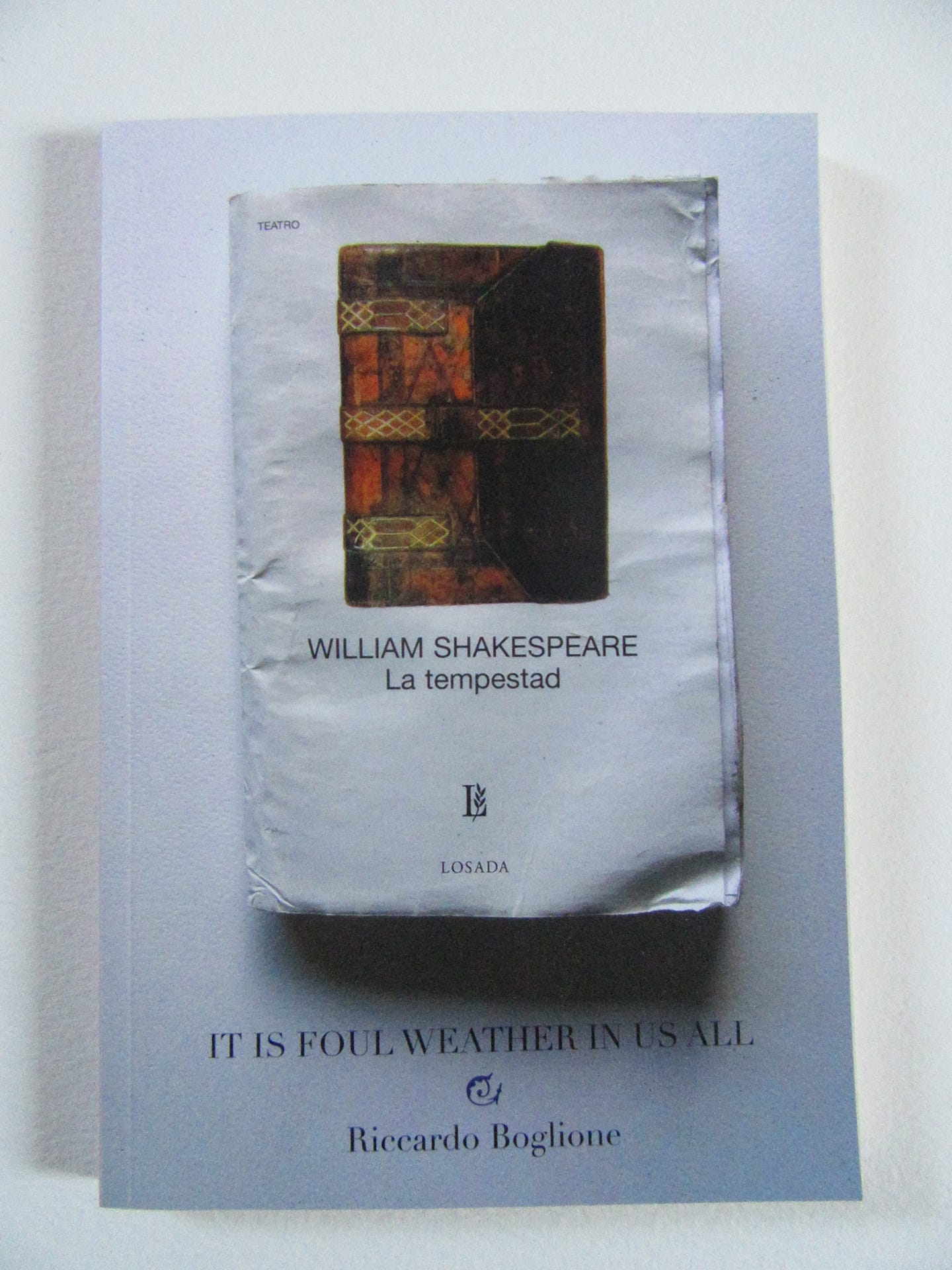

Just because a book doesn’t have a reader, doesn’t mean things don’t happen to it. To produce It Is Foul Weather In Us All (MA BIBLIOTHÈQUE, 2018), Riccardo Boglione posted copies of The Tempest to twelve artists in Europe and North America, each in the language of the country where the artist lived, and requested that the book be left outside. Time passed; winds blew and rain fell; and the books warped and turned. The copies were regathered and the resulting, weather-battered pages were combined to produce a hybrid Tempest: a damaged book that was also now durational, a record of time passing, and of the conditions it had endured.

It Is Foul Weather In Us All is in part about how much happens to a book even when no one is around: how books don’t need readers to transform, and how this is a volume whose author isn’t properly Shakespeare or Boglione, but time, and the elements.

Marcel Duchamp's Unhappy Readymade (1919) is another example of a book left outside, open to the elements. Duchamp created Unhappy Readymade as a wedding gift for his sister Suzanne. He instructed her to hang a Euclidean geometry book on strings in the balcony of her rue Condamine’s Paris apartment, and to expose the ‘knowledge’ in the book to the test of the elements: wind, sun, and rain (and by that, also challenge Euclidean geometry, on its three dimensions). 'The wind had to go through the book, choose its own problems, turn and tear out the pages,' as Duchamp told Pierre Cabanne (in Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, 1987, p. 61). Time and weather had indeed taken their toll on Unhappy Readymade, and the book eroded completely. Although it is suggested that it was later found, hung from a clothesline, at Professor Amalfitano’s backyard in Mexico (Roberto Bolaño, 2666).

The American artist, Ed Ruscha is seen by many as one of the progenitors of the artist’s book as a form in its own right. In his book of interviews, wittily titled, ‘Leave Any Information at the Signal’, Ruscha playfully imagines a character called the Information Man who will sidle up to you and dispense arbitrary facts: “The information man is someone who comes up to you and begins telling you stories and related facts about a particular subject in your life. He came up to me and said, ‘Of all the books of yours that are out in public, only 171 are placed face up with nothing covering them; 2026 are in vertical positions in libraries, and 2715 are under books in stacks. The most weight on a single book is sixty-eight pounds, and that is in the city of Cologne, Germany, in a bookstore. Fifty-eight have been lost; fourteen have been totally destroyed by water or fire; two-hundred sixteen books could be considered badly worn. Three hundred and nineteen books are in positions between forty and fifty degrees. Eighteen of the books have been deliberately thrown away or destroyed. Fifty-three books have never been opened, most of these being newly purchased and put aside momentarily.

“’Of the approximately 5000 books of Ed Ruscha that have been purchased, only 32 have been used in a directly functional manner. Thirteen of these have been used as weights for paper or other small things, seven have been used as swatters to kill small insects such as flies and mosquitos, two were used as a device to nudge open a door, six have been used to transport foods like peanuts to a coffee table, and four have been used to nudge wall pictures to their correct levels. Two hundred and twenty-one people have smelled pages of the books. Three of the books have been in continual motion since their purchase; all three of these are on a boat near Seattle, Washington.’

Now, wouldn’t it be nice to know these things?"