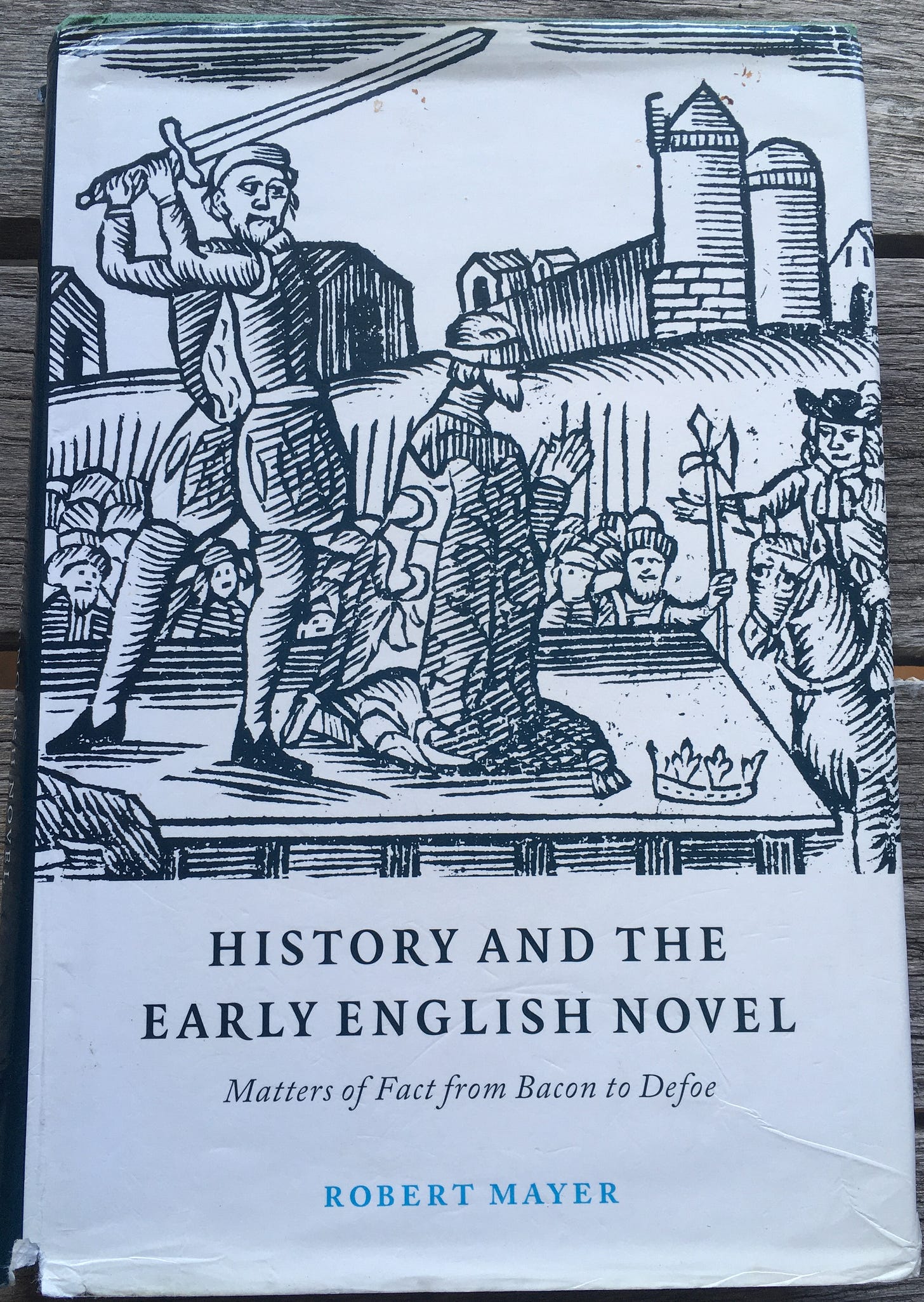

Browsing in a second-hand bookshop on Charing Cross Road some years ago, I came across a copy of History and the Early English Novel by Robert Mayer.

I opened it up and loose papers tumbled out.

Turning the book’s pages, I saw hundreds of annotations pencilled in the margins: shaky lines and ringed numbers and then, across the endleaves and inside back cover, a thick scrawl of largely illegible notes: page numbers, cross-references, summaries, words circled furiously or underlined – ‘21. Facts’; ‘135. Origins of novel’; ‘143-4. Cromwell, Defoe’. What looks like ‘48-9. Milton’s lust’ is probably ‘Milton’s hist[ory]’.

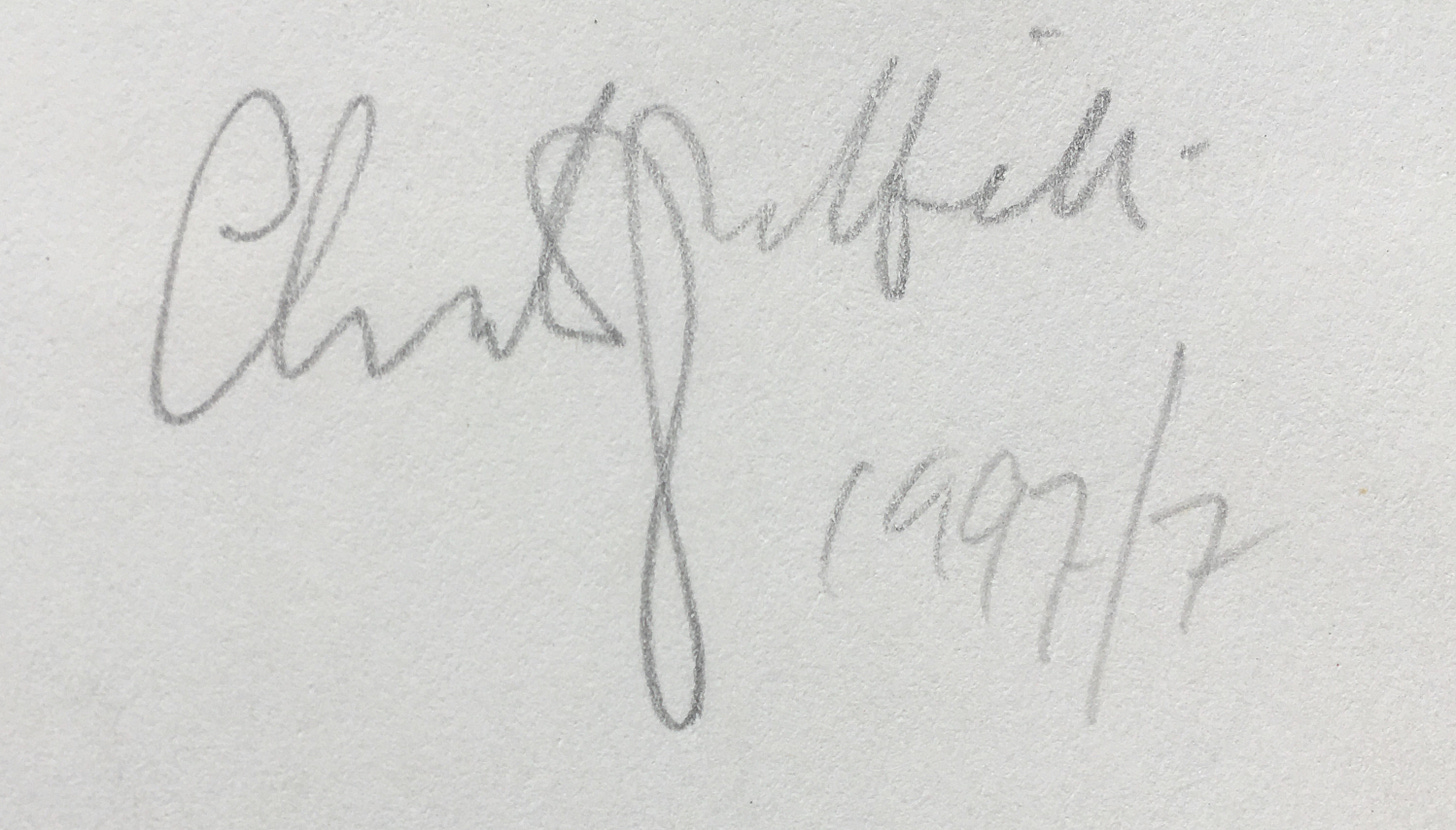

The inside cover has an elegantly looping signature: ‘Christopher Hill/1997/7’. I put the loose papers back and handed over £15. Then I put the book on my bookshelf and forgot about it for a decade.

About ten years later, moving office, I found the book again buried beneath an unhelpfully horizontal stack of other ‘to-be-reads’. According to Keith Thomas, the Marxist historian and academic Hill

used to pencil on the back endpaper of his books a list of the pages and topics which had caught his attention. He rubbed out his notes if he sold the book, but not always very thoroughly, so one can usually recognise a volume which belonged to him.

These notes hadn’t been rubbed out at all, so his copy of Mayer’s monograph must have gone on sale only after he died in February 2003. I spread out the loose pages that had fallen from it. They turned out to be draft notes for a review. Some are in pencil and blue ink, difficult to read, full of abbreviations and Greek letters indicating, I think, insertions. They are scribbled across the backs of two letters: one from Boots Opticians, dated 6 June 1998, suggesting Hill come in for an eye check, signed ‘Sarah Paul, Manager’; the other from Red Pepper, dated 24 August 1998, inviting Hill (‘Dear Investor’) to the AGM on 25 September (‘this has been another difficult year for us financially but an excellent one in terms of the magazine itself’).

There is also a typed draft of the review – the wobbly text suggests a vast and antiquated printer – heavily corrected in pencil. This is printed on the back of page 80 of a draft of Mary Astell’s Political Writings: Biographical Notes, by Patricia Springborg. I didn’t quite know what to do with all this. I read Robin Briggs’s account of Hill in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography: Hill ‘sat curled up in a curious hammock-like chair, beneath a picture of Oliver Cromwell, and made the pupils do all the work.’ Online, I found Hill’s finished review in the autumn 1999 issue of Literature and History and tracked through its relation to the notes and drafts. He took a while to get going. He got Mayer’s book in July 1997; the pencil drafts were written on the recycled letters after 24 August 1998; the marginalia and endnotes obviously made some time in between. The published review is credited to ‘Christopher Hill, Sibford Ferris’. I looked the place up on Wikipedia: ‘The village has a shop and sub-post office.’ I tried to find Sarah Paul, manager of Boots in 1998, but got lost in a forest of namesakes. Robert Mayer teaches English at Oklahoma State University. Patricia Springborg’s edition of the political writings of Mary Astell appeared in 1996. She teaches at the Centre for British Studies at Humboldt University in Berlin. There is both too much and too little here: and that’s the experience of reading an annotated book. Too much to ignore: the jottings and the allusions and the half-comprehensible exclamations are, on one level, irresistible. But there is too little to give much sense of a personality, or of a moment of reading. The many recent studies of the history of reading that draw on marginalia are often written in a prefatory register: here is a beguiling pool of evidence which we can describe, but – what then? What are we to do with annotated books?

A version of this post originally appeared on the London Review of Books blog.

Your photo of Hill's inscription helped me to identify my copy of Ringler's 1962 Sidney as Hill's as well. It could have been in 2003 that I bought it; I left a November 2003 bus pass in the book.

A salutary reminder of how long ago 1973 actually was, when Chris Hill *was* Balliol, and no-one in your current position would have needed to reach for the DNB... Not having studied history, my memories of the Great Man are restricted to, um, disciplinary encounters and "handshaking" (do you still do that?). But I expect others will (may already have) set you straight on that score.

Annotations are a curse in second-hand books (mine particularly, never much more insightful than "!!" or "??" or occasionally "Yes!"): it's impossible not to be diverted by someone else's egotistic highlighting. I blame William Blake and his scribblings on Joshua Reynolds' Works for making them seem respectable ("To generalize is to be an Idiot", etc.). In library books, of course, they are a capital offence: Balliol library, like many others, used to keep a display cabinet of books withdrawn because of "intrusive underlining and annotations" (not sure where they kept the heads of the offenders). Nonetheless, I expect they'd gladly accept this particular vandalised book and its annotations as part of the "old members" collection.

FWIW you'd have more luck following up Fiona Osler. She's very much still around.

Mike