Aspen was a magazine founded by Phyllis Johnson in 1965, published by Roaring Fork Press in New York City. Johnson described it as ‘the first three-dimensional magazine’: each of the ten editions took the form of a box, and the box held a variety of inclusions – papery, and otherwise. In the words of an August 1966 advertisement – think après ski, and mid-60s remake-it-all-optimism – Johnson wrote:

Until now, every magazine was a bunch of pages stapled together. It arrived in your mailbox folded, mutilated, spindled — usually with more ads than editorial. Last year, a group of us enjoying the sun, skiing and unique cultural climate of Aspen Colorado, asked ourselves, ‘Why?’

My copy of Aspen number 4 still hums with this free-wheeling sense of possibility. It’s a hinged box, 24 by 32 by 2cm, with a drawing of a circuit board and wraparound text. The whole is designed by Quentin Fiore and based around the work of Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan, whose aphorisms cover the surfaces of container and contents: ‘all media work us over completely’; ‘joy and revolution’; ‘rite words in rote order’. That kind of thing.

‘The portfolio comprises many parts,’ wrote Johnson, ‘created and produced separately, in different media, by different processes; then combined, collated, and individually assembled and shipped.’ Among number 4’s box-held parts are a fold-out poster of pages from McLuhan and Fiore’s The Medium is the Massage; a colour poster of the Tribal Stomp at San Francisco's Avalon Ballroom; an essay on electronic music by Faubion Bowers and Daniel Kunin; a ‘flexidisc’ recording of early electronic music by Mario Davidovsky and Gordon Mumma (‘for French Horn and Cybersonic Console’); a John Cage prose poem titled ‘How To Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse)’; and a description of a nature trail for the blind. Even the advertisements follow this jostling-atoms format: a folder contains small booklets and sheets for the Sierra Club, United Airlines, MGB autos, Remy Martin, and others. (You can read digital scans of the contents of all 10 editions of Aspen on Ubu Web.)

There are lots of stories here. One is about Phyllis Johnson (1926-2001), known outside of Aspen by her married name of Glick. Johnson has been largely neglected by scholarship, but she was someone who combined work as a journalist and editor on mainstream papers and magazines (Nebraska State Journal, Women’s Wear Daily, Advertising Age, American Home Magazine) with co-ordinating a radical experiment in publishing. There’s an exuberance to everything Johnson writes – ‘who knows what the next issue will be!’; ‘ASPEN gives you actual works of art!’ – and, by some criteria, she was astonishingly successful: later editions of Aspen feature pieces by Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag, Timothy Leary, Robert Rauschenberg, Samuel Beckett, Sol LeWitt, J.G. Ballard, Yoko Ono, and John Lennon. Aspen 3 was designed by Andy Warhol and came in what looked like a package of Fab laundry detergent. Aspen 5 and 6 – the Minimalism issue – arrived in a two-piece white box with contributions by Marcel Duchamp, Merce Cunningham, William S. Burroughs, and Morton Feldman: 8mm reels of film, essays, music scores, and DIY miniature cardboard sculptures. Aspen 9 – the Psychedelic Issue, subtitled ‘Dreamweapon’ – had the words ‘Lucifer, Lucifer, Bringer of Light’ printed on the back and included inside Benno Friedman’s chemically stained frames from Western movies.

Johnson deserves a key place in that long history of female editors of journals that to a considerable extent shaped the literary and artistic landscape of the early to mid-twentieth-century: a history that includes Harriet Shaw Weaver, whose The Egoist serialised James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in 1914; and Margaret Anderson, whose Little Review (1914-29) did the same for Joyce’s Ulysses; and Harriet Munroe, whose Poetry magazine from 1912 published early work by Wallace Stevens, H.D., and was the first to publish T.S. Eliot’s ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock’ – and which, triumphantly, still exists today. (The entire archive of Poetry is available here, for free). We need to know more about Johnson, whose ashes were scattered in the sea off Hawai'i in 2001, and who was described by a long-time friend as ‘excellent in everything she did.’

The other story is a material one. What happens when we imagine a magazine as a box? In her introductory letter to edition 1, Johnson wrote that by using the term ‘magazine’,

we are harking back to the original meaning of the word as ‘a storehouse, a cache, a ship laden with stores.’ That's what we want each issue to be. Since it comes in a box, our magazine need not be restricted to a bunch of pages stapled together… [and we] can put in all sorts of objects and things to illustrate our articles.

A box enables a level of coherence – hence the themed issues – but, within this, an in-flux miscellaneity. Shake the box and the contents rattle. Empty the box and the parts fall in a random order. Remove an item and you can keep it apart. Place them back, one by one, like you’re packing a lunch. Add a component of your own. Close the lid knowing they’ll still be there, waiting until next time. (If you like your books as boxes, look out for two forthcoming titles: Gill Partington’s Page Not Found, on alternate formats, and Lucy Razzall’s Boxes and Books in Early Modern England.)

The U.S. Postal Service didn’t like Aspen’s erratic publication schedule, and revoked the second-class mail license granted to newspapers and magazines: without the license, Johnson couldn’t afford the postage costs and Aspen folded. In the judgement of 9 April 1971, Chief Hearing Examiner William A. Duvall declared Aspen to be ‘nondescript’ – in the sense of ‘unclassifiable; belonging, or apparently belonging, to no particular class or kind’ – and lacking qualities necessary to qualify as a ‘periodical publication’. It was the very free-standing coherence of each edition that meant, according to Duvall, that Aspen couldn’t be classed as a magazine. As a collision of avant garde art and careful legal argumentation, the judgement has a nice absurdity about it.

After careful study of the record and such authorities as exist, I find that “Aspen” is not a “periodical publication” within the meaning of 39 U.S. Code 4354. Each issue deals with a single subject. It is true that this subject is treated in different ways in the various “sections” of the publication, but each section in one way or another bears upon the central topic of the issue in which it appears. Each issue is complete unto itself and it bears no relation to prior or subsequent issues and can be considered to be an independent work, capable of standing alone. It is true that periodicity is, if not an attainment, at least a goal of the publisher but, because of the complete way in which a subject matter is treated, periodicity (as in the case of the publications under consideration in Houghton v. Payne, supra) is not an element of their character.

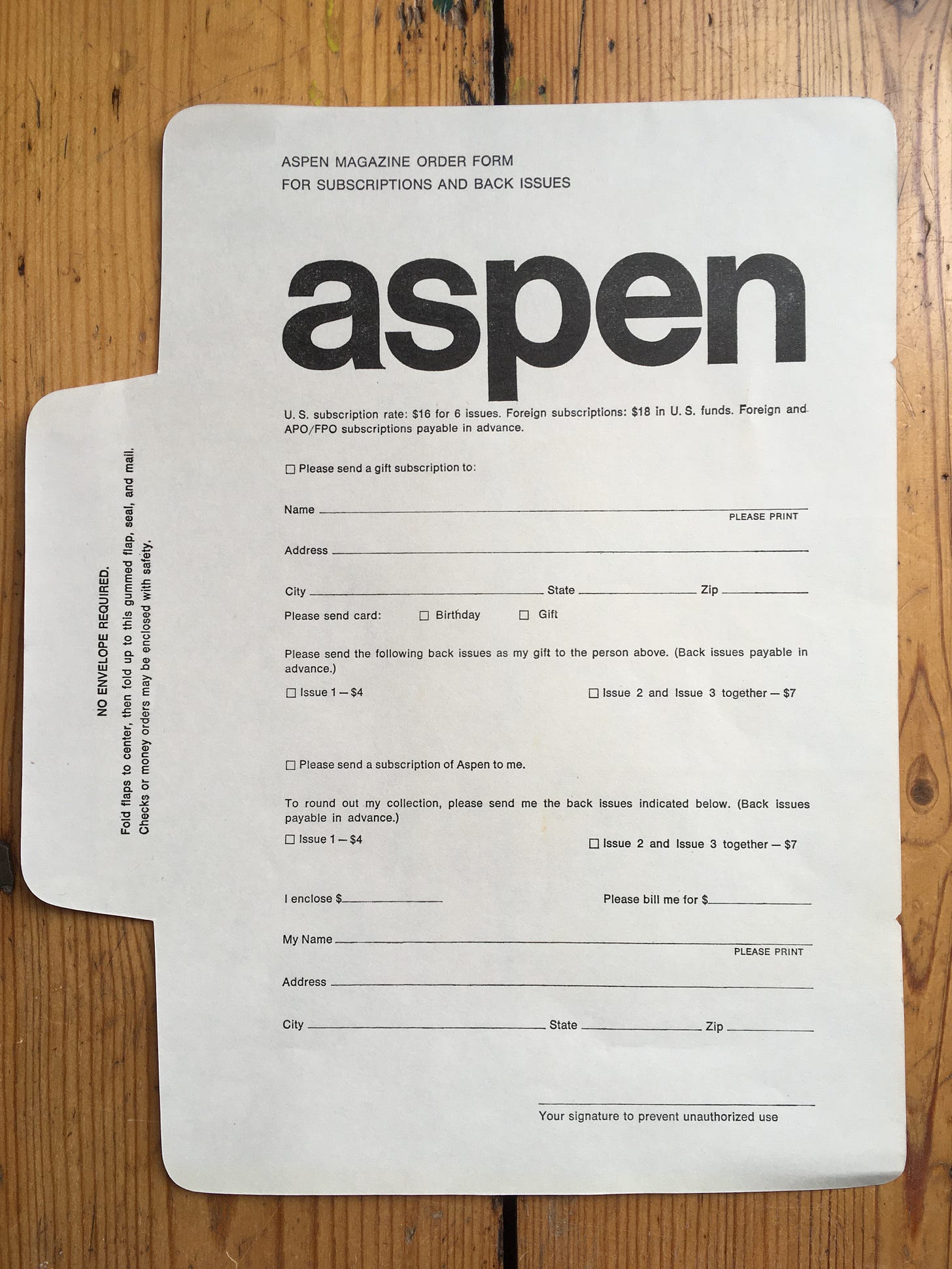

The most affecting item in number 4 is the order form:

It’s a piece of ephemera that takes us back to the moment when Aspen was new, and had plans to run and run on through the years. I wonder what would happen if I tick the box and fold the form (‘No envelope required’) and mail it in. ‘We'll guarantee you,’ writes Johnson,

that our magazine is in fact as great as it sounds in concept. If you hate it, you can cancel at any time and get a pro-rata refund promptly. You have nothing to lose — and at the very least a conversation piece and collector's item to gain.

Let's go.

Hello.

Great article!

May I ask where you got the first quote by Johnson from? (The one about skiing in Aspen and questioning the nature of the magazine.)

Not dissimilar to the fate of Ed Ruscha's 'Twentysix Gasoline Stations' which was returned to him by the Library of Congress, regarded as being too categorically nebulous for their collections. Ruscha later added REJECTED to his ad plugging the book in 'Artforum'.