Among the many works of Barbara Rosenthal – an American avant-garde artist, writer and performer (b. 1948) who sometimes goes by the name of Homo Futurus or Cassandra-on-the-Hudson – is a slim text called “The Allan Project”. This was published 22 years ago as a second part to a longer work called ‘Names/Lives’. In a preface to the 11-pages of “The Allan Project”, Rosenthal explains that in the early 1990s, she began to notice that there were

a good many men whose first names were “Allan” with that spelling. The photography critic A.D. Coleman, whose first name is spelled “Allan”, had, many times in my hearing, reflected on his parents’ choice of the least common of the spellings. It seemed difficult to pass up the blurbs I found, introducing a multitude of new “Allans”, and so for a few years I collected these, as “The Allan Project,” originally presented as a wall-piece to A.D. Coleman himself so that he will have company.

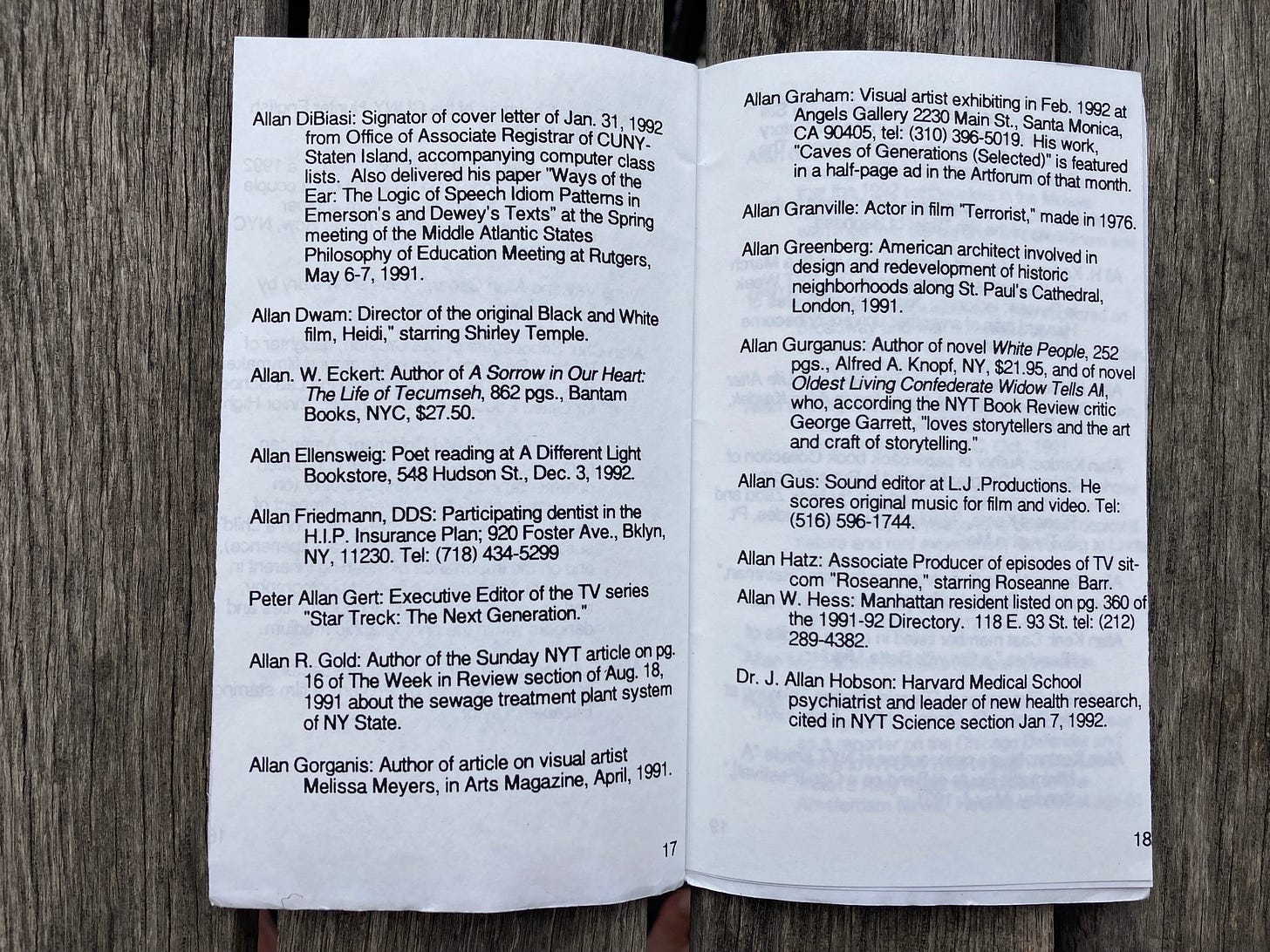

Rosenthal gives us lists of some of these Allans. Here are four pages:

Since only the spelling of the name “Allan” binds these individuals together, the pleasure of the piece is the diversity of lives arranged in alphabetical order: individuals who we might say have nothing to do with each other, methodically gathered into a closed field of “Allan”. Allan Brick, Chairman of the CUNY-Hunter English Department; Allan K. Rich, actor listed in rolling credits as playing the D.A. in the American film Serpico; Allan Shapiro, owner of two miniature Shetland ponies whose escape from their barn hit the pages of The Berkshire Eagle, July 30, 1991. Famous Allans (Edgar Allan Poe; Allan Arbus) jostle next to little-known Allans (‘Allan Friedmann, DDS: Participating dentist in the H.I.P. Insurance Plan’).

The work has several effects, and one of them is to show us that the list, as a form of writing, is inherently funny. Writing in 1962, and making a broader argument about the importance of mathematics to modernist writing, literary critic Hugh Kenner suggested that

[t]o adduce lists, to enumerate or imply the enumeration of their elements and then permute and combine these elements: this, [James] Joyce seems to imply, is the ultimate recourse of comic fiction.[1]

Rosenthal’s text is typed, Xeroxed, 4” by 6”, staple bound and sold for $10 (or $15 signed). It was published in 2001, before the Internet felt inevitable, on that fold in media time when relations between print and digital were starting to shift. The D.I.Y materiality of ‘The Allan Project’ is important. The internet’s capacity today to immediately give us back what we search for has in many ways cancelled this kind of work-through-chance whose meaning, if it has meaning, is built on the gradual accumulation of Allans as they presented themselves to Rosenthal while she was going about other things – watching the credits on TV, or reading the local newspapers. We feel that slowness of production as we read. There is nothing interesting about Googling “Allan” to find at once a list of them: one of the things Rosenthal’s piece shows us is the unfakeable power of a durational process of making.

Barbara Rosenthal’s many projects are detailed here.

[1] Hugh Kenner, ‘Art in a Closed Field,’ in The Virginia Quarterly Review Vol. 38, Iss. 4, (Fall 1962), 597-613, 604.

This is fun, but for sheer entertainment value I think I prefer the contemporaneous adventures of comedian Dave Gorman who, after a drunken bet, hunted down people sharing his own name (including two women who changed their name by deed poll), which became the stage show "Are You Dave Gorman?" (broadcast by BBC as "The Dave Gorman Collection" in 2001).

Mike