The problem of what to do with stuff. When my grandfather died, he left a number of plastic bags full of papers and documents. Had he been illustrious or famous or an individual of obvious public significance, I would have sent the papers along to Kent Archives, near where he lived, where they would have been catalogued and preserved for a future historian of Westerham, or someone researching the role of churchwardens during the second world war, or an author writing the history of unfulfilled amateur poets. Had the papers been of no interest, I might have binned them. But the letters and notes and drafts fell somewhere between these two poles: impossible to throw away, but with no obvious purpose or destination. This sort of mid-range documentation presents an interesting problem.

There are at least a couple of things one could do with the contents of the plastic bags. The first would be to make something new out of the old papers: like a collage, as below, patched from small selections of the many hundreds of letters and other pieces of paper. The nice thing about preserving in collage, as opposed to in an archival box, is the sense of pieces of text in motion, moving around in an atmosphere they have created. Another nice thing is that the collage becomes something to look it (it hangs on my bedroom wall), and also, at the same time, a way of archiving: the collage is a means of gathering together papers for a time, until some point in the future when those papers acquire a purpose and can be released

Here is the inked blotting paper, and the business notes from ‘late 1943’, and the drafts of poems written (Emily Dickinson-style) on recycled envelopes, and the dust jacket to Virginia Woolf’s The Years. (For reasons I don’t quite understand, my grandfather hated dust jackets, seeing them I think as crassly excessive; he removed them from books on purchase and used their reverse for shopping lists, writing with a sense of both utility and punishment).

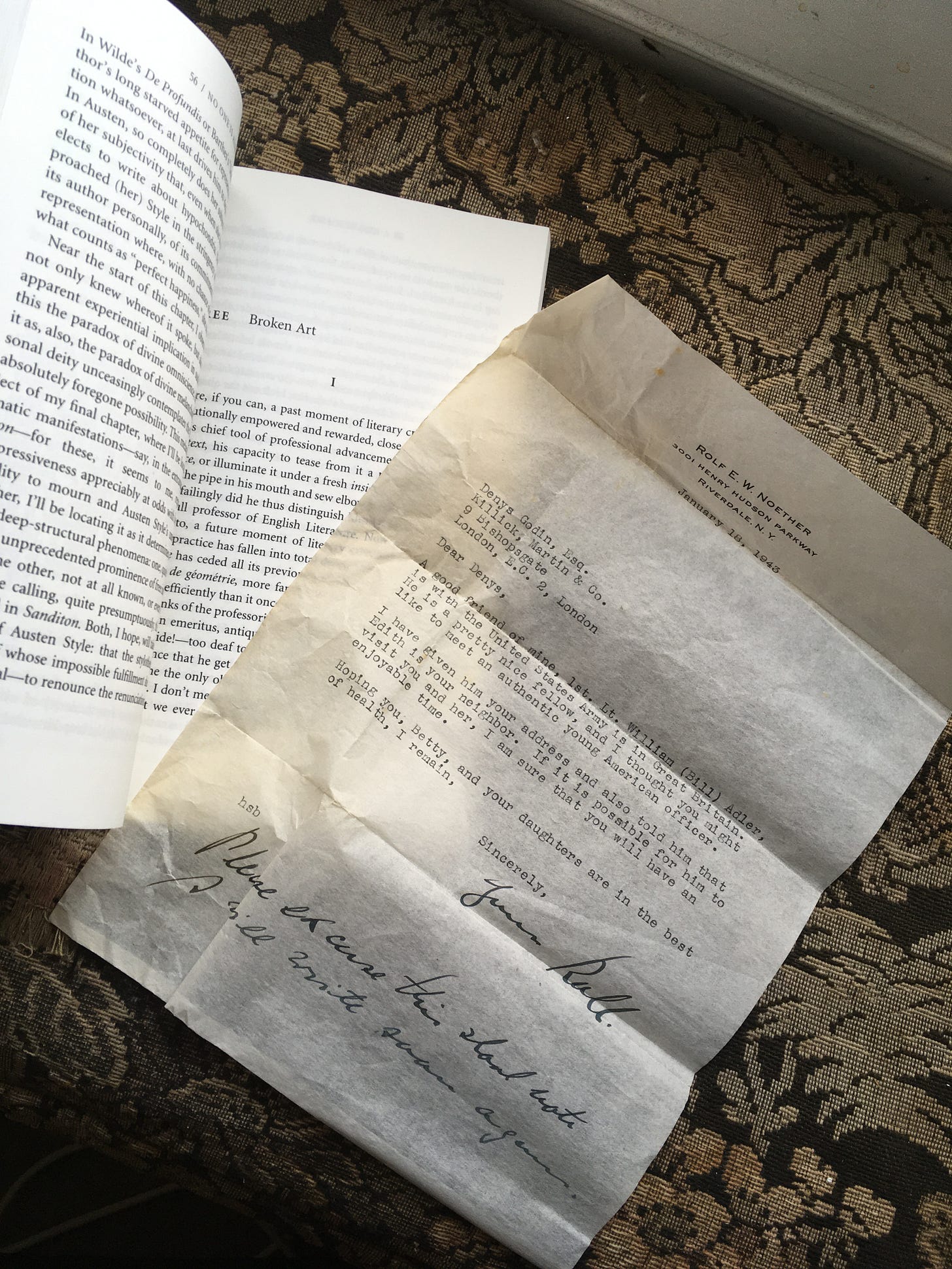

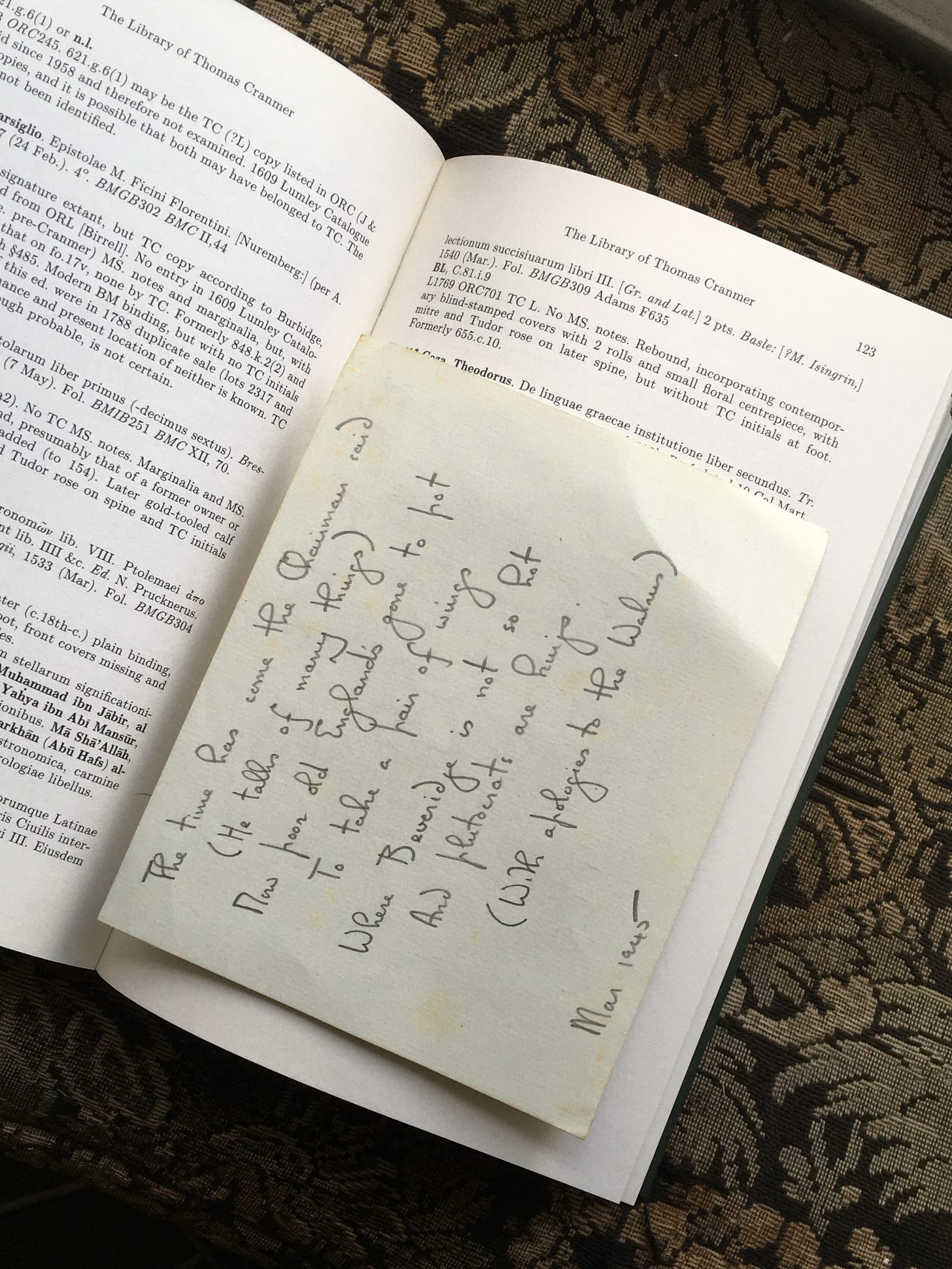

That was response number one to the plastic bags of papers. Response number two would be to place individual letters, papers, doodles, and drafts between the pages of lots of books, one item per book. When I did this, I didn’t chose the book titles with any deliberation, but inevitably certain effects-through-juxtaposition occurred. The dog licence tucked among the pages of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The letter of 18 January 1943 from New York introducing American officer 1st Lt. William (Bill) Adler, ‘a pretty nice fellow’, in a copy of D.A. Miller’s Jane Austen, or The Secret of Style. Here are four examples of many.

The most interesting effect of doing this is the impression of touching time: both when putting a letter in a book and then placing the book on the shelf, and not knowing how many years will pass before it’s seen again; and in the moments of chance retrieval – opening a copy of the catalogue of The Library of Thomas Cranmer, for example, unread for years, and finding part of a poem from March 1945, long forgotten. Two bookish affordances are at work here: the book as a container for something else, and the book as an object likely to endure through time.

Thank you for sharing all of this. It's a problem we can all relate to and your solutions are those of a person who has thought deeply about books and materiality. I'm feeling very inspired by this post. (I, too, have boxes of family papers.) So, I'll echo Mike Park's request: can you tell us more about the materials you used?

You have to wonder, did Mr. Godin live in Digon Lodge because of some anagrammatic nominative determinism, because he had the place built, or because he couldn't resist renaming it?

Mike